Background: Approximately 45% of all Americans suffer from 1 or more chronic diseases, which are among the most prevalent and costly health conditions in the United States. Recently, studies have focused on how a chronic disease navigator may contribute to improved clinical and financial outcomes.

Objective: To investigate and analyze articles related to navigators of various diseases to provide an evidence base for the development of an interprofessional network platform.

Methods: A 3-step search strategy was undertaken: (1) an initial limited search of PubMed and MEDLINE; (2) an extensive search using all identified keywords and index terms across all included databases (Appendix I); and (3) a hand search of the reference lists of included articles.

In addition to utilizing the results from the scoping review, online surveys were conducted to gather information from AONN+ membership regarding their knowledge of chronic illness navigators working at their healthcare institutions, as well as surveys conducted with these chronic illness navigators about the types of chronic diseases they navigate, and what they see as their career growth needs.

Results: A total of 2826 articles were screened, 642 full-text publications were reviewed, and 33 relevant articles were identified. The most common navigator terms were care manager and nurse navigator. The most common chronic diseases included in the articles were related to cardiac and respiratory disease.

In the AONN+ survey of 138 member respondents, 62% reported that other chronic disease navigators existed at their institution, with 64% reporting that there are 1 to 5 chronic disease navigators at their institution. In a survey of 68 chronic disease navigators, 27% reported working as a clinical nurse prior to becoming a chronic disease navigator, and nearly 70% reported having a master’s or doctorate degree. Three key opinion leaders (KOLs) were also interviewed one-on-one to learn what they have experienced over time and what their experiences are currently within the chronic illness navigation space.

Conclusion: The most common chronic disease navigators are characterized as care managers and nurse navigators, with the most articles related to cardiac and respiratory disease. Additional research is needed related to measures of the full scope of success of these chronic disease navigators. Inclusion of all relevant navigator terms and chronic diseases will be beneficial for developing an interprofessional network for these navigators caring for patients with chronic diseases. Information was provided as an outcome of conducting interviews of KOLs working and publishing in the chronic illness nurse navigation space, confirming the value of patients having chronic illness nurse navigators from a financial outcomes and clinical outcomes perspective. In some cases, the nurse navigators were referred to as “transition nurses.” (See Appendix II for a detailed example of measuring a specific model developed and used by a KOL working in the clinical setting, as well as additional articles published by this KOL.) Surveys conducted online with AONN+ membership and chronic illness navigators demonstrated the growth of this profession nationally. Results revealed the need for a professional organization to support these navigators to further their knowledge of navigation; to stay up-to-date on diagnosis and treatment changes and improvements continuously being made for their patients; to provide opportunities for networking; and to support career advancement. Professional development would include measuring clinical and financial outcomes, improving efficiency in the delivery of care, establishing standards of care and guidelines for chronic illness navigation practices, and promoting more team-based care.

Approximately 45% of all Americans suffer from 1 or more chronic diseases, which are among the most costly and prevalent conditions in the United States.1-3 Chronic diseases include diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart disease, respiratory diseases, and obesity and can result in hospitalization, reduced quality of life, long-term disability, and death.4,5 Persistent conditions have been demonstrated to be the leading cause of disability and death in the United States.4 In the United States, chronic diseases contribute to approximately 75% of aggregate healthcare spending.6

Currently, 1 in 4 US adults have at least 2 chronic conditions, and over 50% of older adults have at least 3 chronic conditions.3 Based on an increasing likelihood of developing comorbidities with age and 10,000 Americans turning 65 each day through the end of 2029, the overall population with comorbidities will substantially increase.

Causes of Death in 2017 in the United States

The leading causes of death for Americans reported in 2017 included heart disease (23%), cancer (21%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 5.7%), Alzheimer’s disease (4.3%), diabetes (3%), and kidney disease (1.8%).7

It is important to note that more patients with cancer are being treated with the cancer diagnosis being recognized as a chronic illness. Additionally, some chronic diseases increase the risk of getting cancer (ie, a patient with COPD is at a higher risk of developing lung cancer; a cancer survivor is at higher risk of developing heart disease based on the type of treatments they received that can cause cardiotoxicity).

Looking Closer at the Incidence of Chronic Illnesses That Are Formally Tracked Statistically

Diabetes

Among the overall US population, crude estimates for the prevalence of diabetes in 2018 was 34.2 million people of all ages (10.5% of the US population), including 34.1 million adults aged 18 years or older (13.0% of all US adults).5 Furthermore, there were 7.3 million adults aged 18 years or older who met laboratory criteria for diabetes but were not aware of or did not report having diabetes, which is considered undiagnosed diabetes, representing 2.8% of all US adults and 21.4% of all US adults with diabetes. The percentage of adults with diabetes increased with age, totaling 26.8% of individuals aged 65 years or older.

Among the overall US population, 26.9 million people of all ages (8.2% of the US population) had diagnosed diabetes, which included 210,000 children and adolescents younger than age 20 years and 187,000 with type 1 diabetes.5 Of these, 1.4 million adults aged 20 years or older reported having type 1 diabetes and using insulin. Additionally, 2.9 million adults aged 20 years or older started using insulin within 1 year of their diagnosis.

Among US adults, age-adjusted data for 2017-2018 indicated that the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.7%), people of Hispanic origin (12.5%), non-Hispanic blacks (11.7%), non-Hispanic Asians (9.2%), and non-Hispanic whites (7.5%). The highest prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in women was reported in American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.8%). Among men, American Indians/Alaska Natives had a significantly higher prevalence of diagnosed diabetes (14.5%) than non-Hispanic black (11.4%), non-Hispanic Asian (10.0%), and non-Hispanic white (8.6%) men. The prevalence varied significantly by education level: 13.3% of adults with less than a high school education had diagnosed diabetes compared with 9.7% of those with a high school education and 7.5% of those with more than a high school education.

The National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 provides analysis of health data through 2018, including statistics across ages, races, ethnicities, education levels, and regions.5 Data from this report provide vital perspectives on the current status of diabetes and can help focus prevention and management efforts going forward. An estimated 34.2 million Americans (just over 1 in 10) have diabetes. An additional 88 million American adults (approximately 1 in 3) have prediabetes. New cases of diabetes were more frequently reported among non-Hispanic blacks and people of Hispanic origin compared with non-Hispanic Asians and non-Hispanic whites.

Among adults diagnosed with diabetes, there was a significant decrease in new cases from 2008 through 2018. The highest percentage of existing cases was reported among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Overall, among patients with diabetes, 15% were smokers, 89% were overweight, 38% were physically inactive, 37% had chronic kidney disease, and fewer than 25% with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease were aware of their condition. Among US youth, there has been a significant increase in newly diagnosed cases of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with the incidence of type 2 diabetes remaining stable among non-Hispanic whites and increasing for all other groups, particularly non-Hispanic blacks. Although the percentage of adults with prediabetes who were aware of the condition doubled between 2005 and 2016, most remain unaware.

In 2017, diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States based on 83,564 death certificates with diabetes listed as the underlying cause of death. Diabetes was mentioned as a cause of death in a total of 270,702 certificates. However, diabetes may be an underreported cause of death because only 35% to 40% of people with diabetes had diabetes listed on the death certificate, and only 10% to 15% had it listed as the underlying cause of death.

The total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes in the United States in 2017 was $327 billion, with $237 billion for direct medical costs and $90 billion due to reduced productivity. Adjusted analyses revealed that the average medical expenditures among people with diagnosed diabetes were more than twice as high as expenditures reported in the absence of diabetes.

Heart Disease

In the United States, heart disease is the leading cause of death for men, women, and people of most racial and ethnic groups, with 1 person dying every 36 seconds of cardiovascular disease, totaling about 655,000 Americans annually.8 For women from the Pacific Islands and Asian American, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hispanic women, heart disease is second only to cancer. Heart disease contributed to an estimated cost of $219 billion from 2014 to 2015, which included costs of healthcare services, medicines, and lost productivity due to death.

The most common type of heart disease is coronary artery disease (CAD), which contributed to 365,914 deaths in 2017.8 Approximately 18.2 million adults aged 20 years and older have CAD (about 6.7%). Knowing the warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack is critical to improve the likelihood of a patient being treated and surviving the event. Each year, approximately 805,000 Americans have a heart attack, including 605,000 first heart attacks and 200,000 subsequent heart attacks.

Lung/COPD

COPD includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis and is the fourth leading cause of death and the third most common cause of disability.9 The estimated annual costs of patient-related care totaled $49 billion for 2020. COPD affects 16 million people and millions more who do not know they have it.10 More than 65 million people worldwide have moderate or severe COPD, and experts predict that this number will continue to rise over the next 50 years. With proper management, most people with COPD can achieve good symptom control and quality of life and reduce their risk of other associated conditions, including heart disease and lung cancer.

In 2014, the prevalence of COPD varied considerably by state.11 The states with the highest COPD prevalence are clustered along the Ohio and lower Mississippi rivers. Age-adjusted death rates due to COPD declined among US men from 1999 (57.0 per 100,000) to 2014 (44.3 per 100,000); however, death rates have not changed among US women (35.3 per 100,000 in 1999 and 35.6 per 100,000 in 2014). Since 2000, more women than men have died of COPD in the United States.12 Furthermore, in 2017, COPD was the third leading cause of death among US women. More women than men are also living with COPD in the United States. Women tend to be diagnosed later than men, when the disease is more advanced and treatment is less effective.

Patient Navigators

To help patients overcome certain modifiable barriers to care and to achieve their care goals, personnel have been trained as patient navigators to provide an individualized approach to addressing the needs of each patient.13-15 These navigators may be lay health workers, social workers, or nurses. Initially established to decrease gaps in cancer care in marginalized populations, patient navigator programs are becoming more widespread in the United States and Canada for cancer care.16,17 In addition, patient navigation programs exist for cancer screening, smoking cessation, and diabetes.18-21 Navigator responsibilities may include disease or health system education, removing medical system barriers, assisting with insurance coverage, addressing additional financial barriers, aiding to coordinate care, referring patients to community resources, and providing emotional support.16,22-26

A recent AONN+ survey demonstrated that navigators are covering chronic disease areas, including respiratory, cardiac, diabetes, orthopedics, and obesity, among others, demonstrating the need in these areas.27 The majority of institutions (64%) reported having 1 to 5 chronic illness navigators, followed by 6 to 10 navigators (24%), more than 16 navigators (8%), and 11 to 15 navigators (4%). Interestingly, when asked whether they engage with a society, approximately 40% responded with the American Nurses Association, whereas the rest were distributed among approximately 20 other associations, with many respondents unsure of a relevant association.

According to a survey respondent, “Many patients with a chronic illness are managing their disease and its treatments well, but there is a portion of patients who do not. Underinsured, uninsured, and homeless people also have behavioral health issues, limited finances, are unemployed, have multiple chronic illnesses and acute serious illness happening on top of already having chronic illnesses that may be difficult to manage. The patient is assessed for these barriers and complex needs.”

Objective

The objective of this scoping review was to identify trends in navigation practice within the chronic disease space.

Methods

Search Strategy

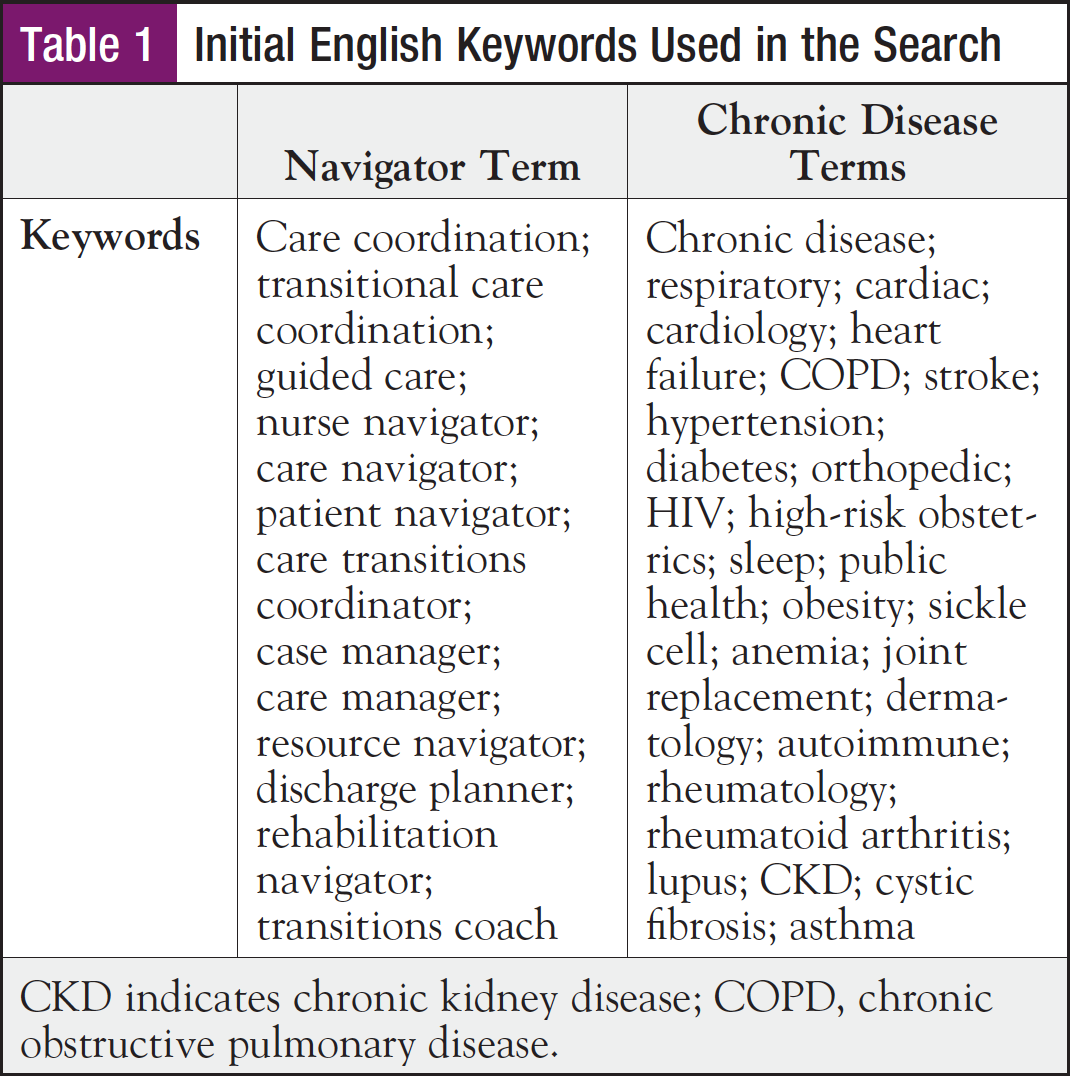

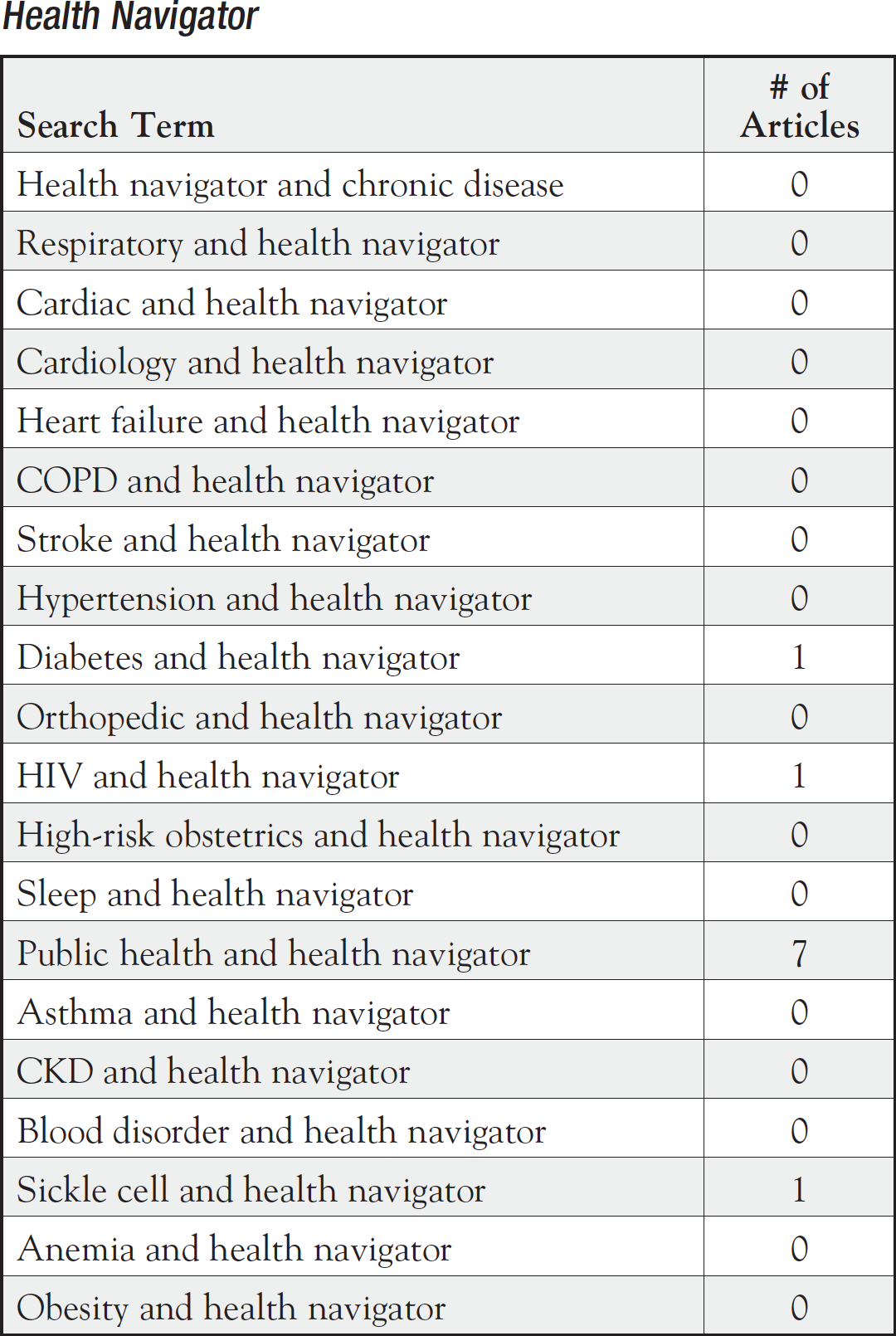

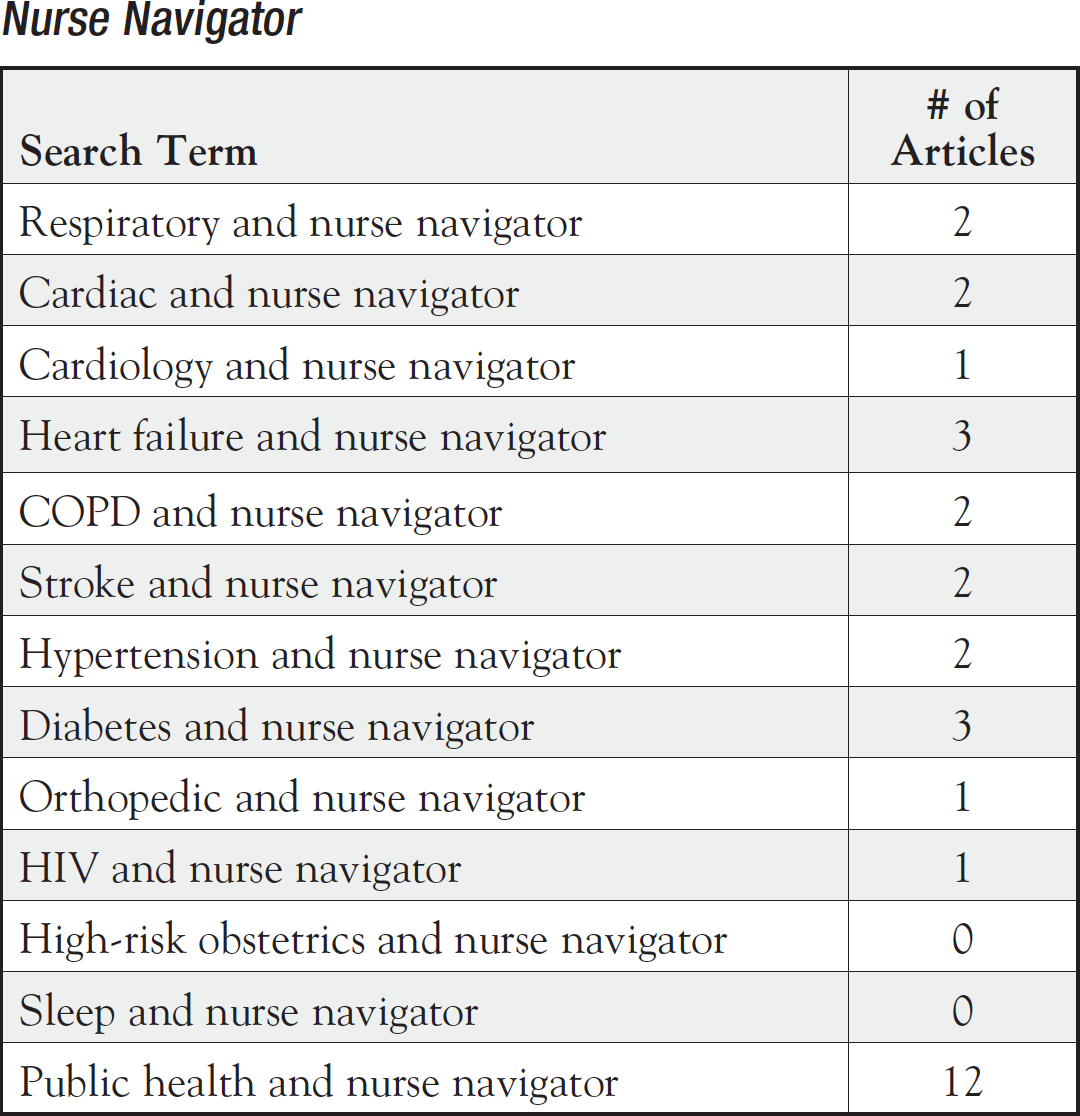

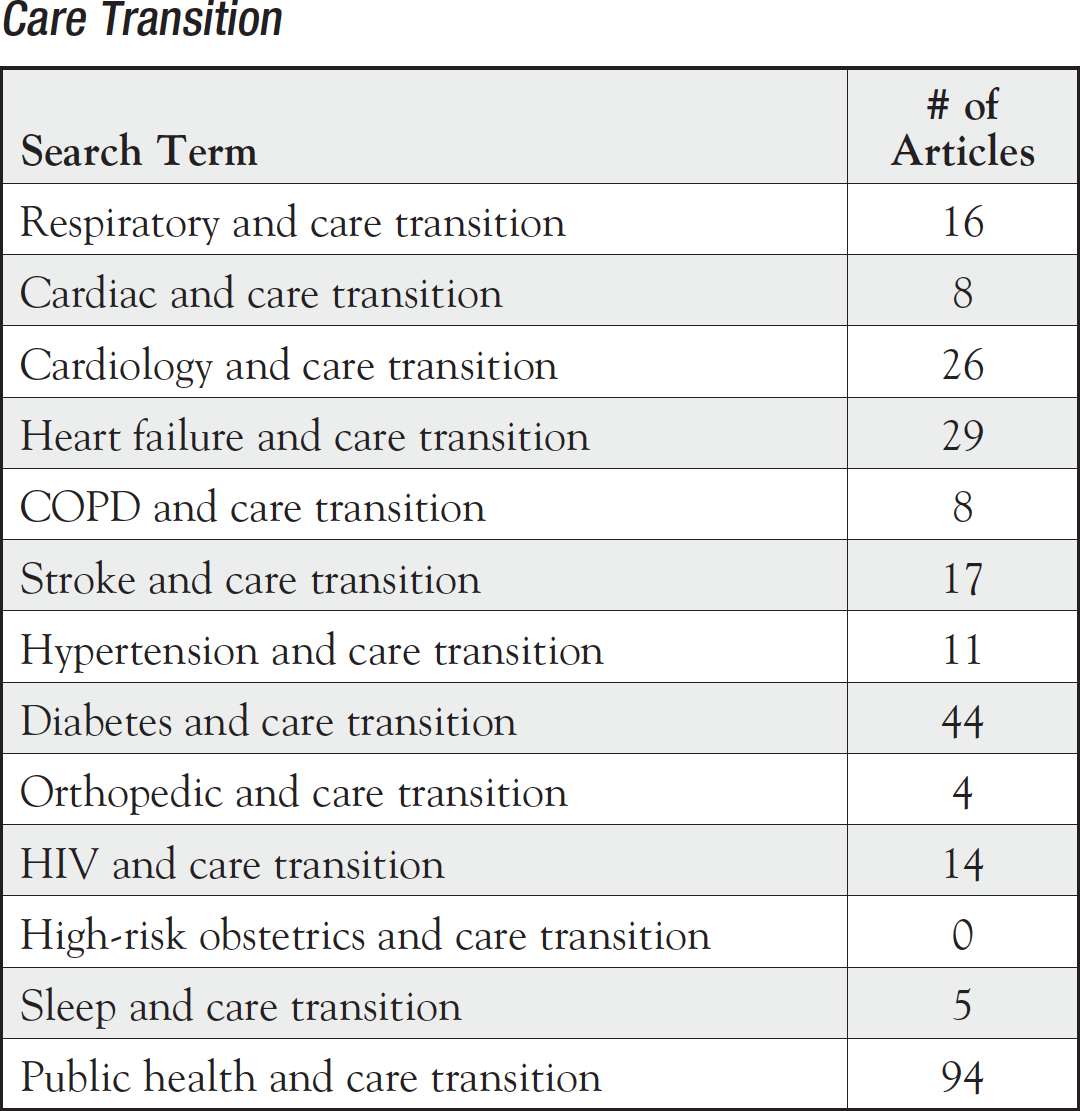

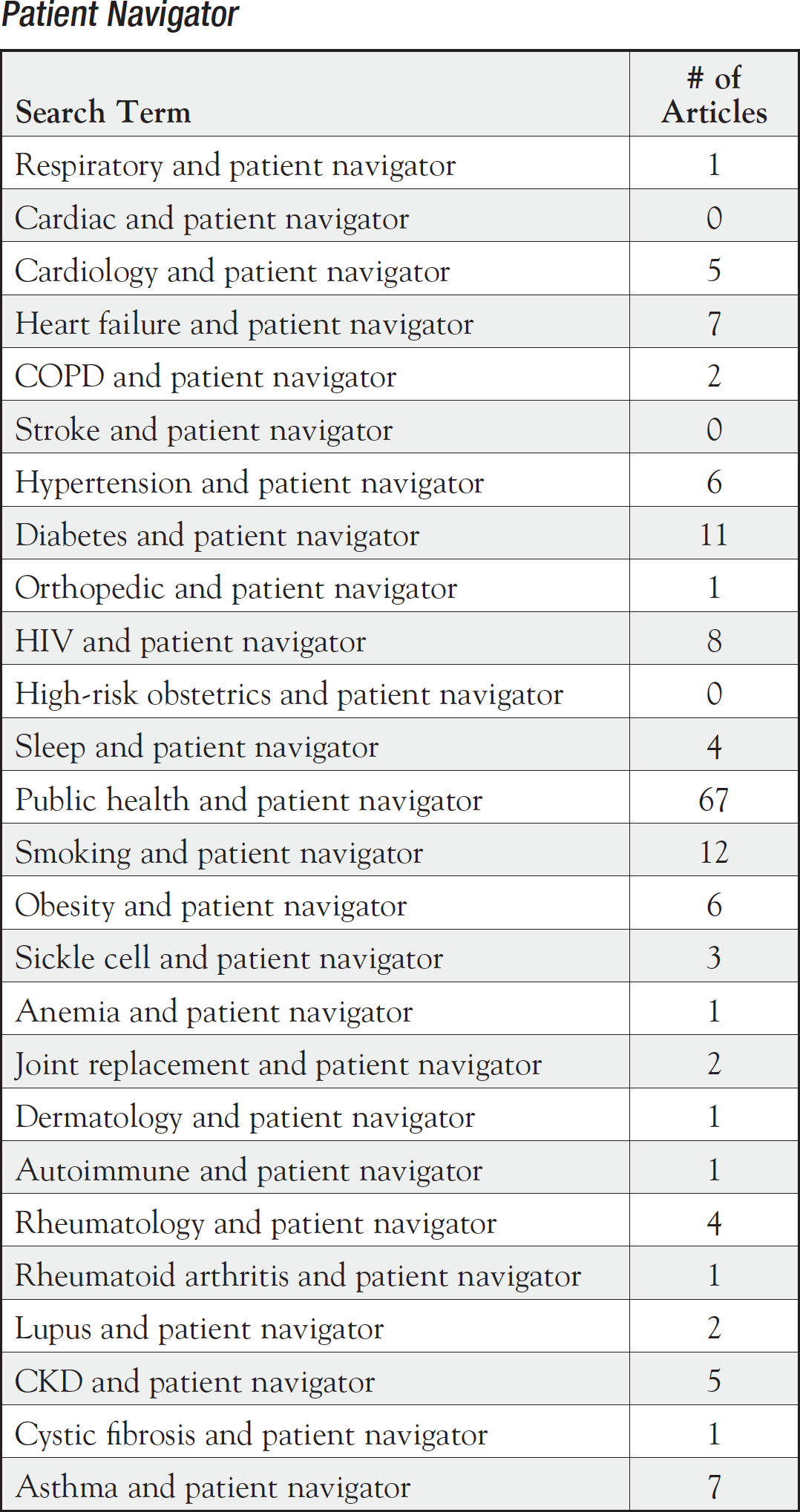

Utilizing the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review method, a 3-step search strategy was undertaken: (1) an initial limited search of PubMed and MEDLINE; (2) an extensive search using all identified keywords and index terms across all included databases; and (3) a hand search of the reference lists of included articles. This review was limited to studies published in English from 2010 to 2020. Keywords used in the search are shown in Table 1. The full search strategy, including all identified articles, is presented in Appendix I.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) model was applied to identify articles centered on navigators of patients with chronic diseases, which were assessed for relevance to the review using information provided in the title and abstract by 2 independent reviewers. If the reviewers had doubts about the relevance of a study from the abstract, the full-text article was retrieved. The full-text article was retrieved for all studies that met the inclusion criteria of the review. Two reviewers independently examined the full-text articles to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. Any disagreements that arose between reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Extraction of Results

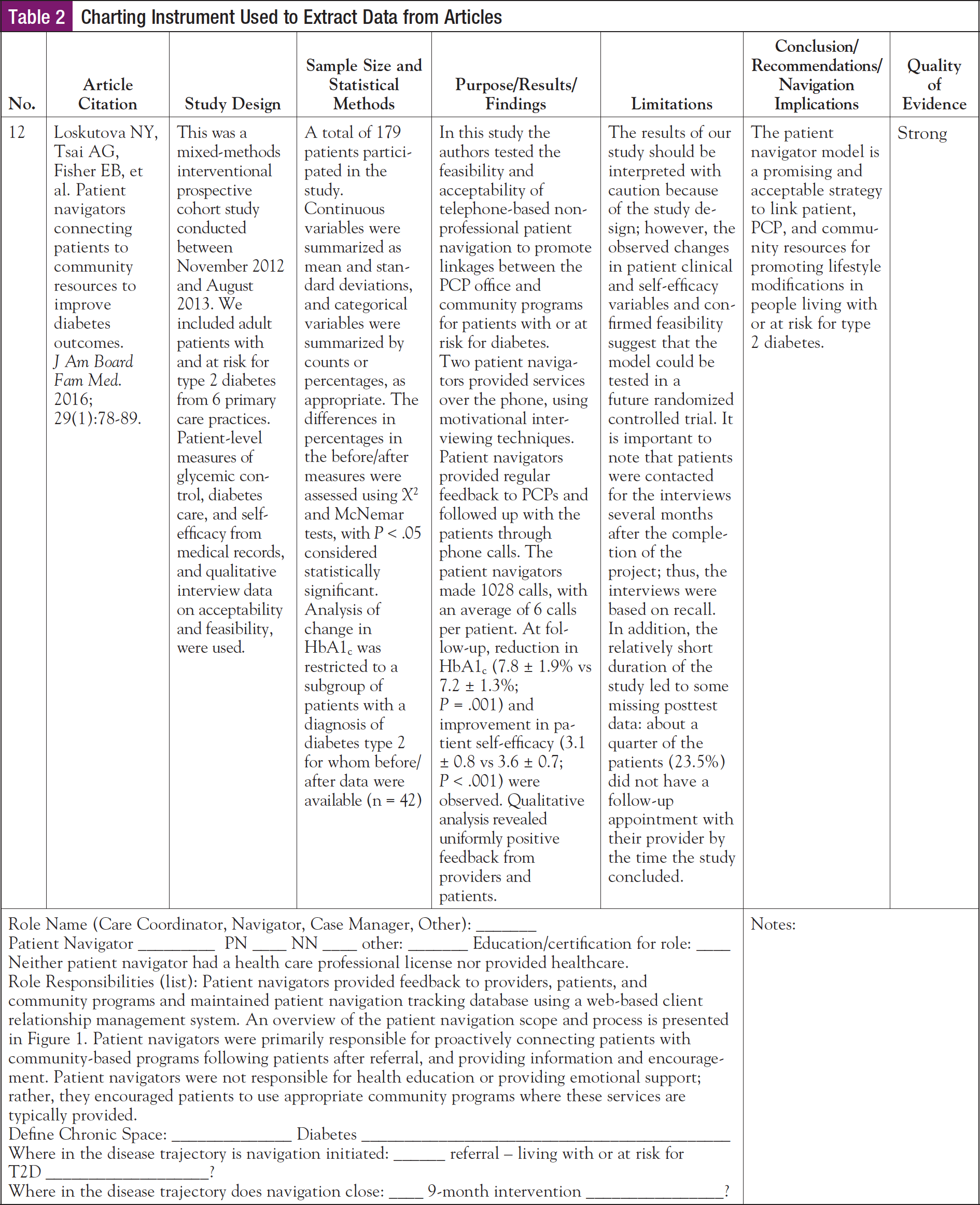

From included articles, data were extracted using a charting instrument aligned with this research objective and question (Table 2). Study details and characteristics extracted included the following: authors, year of publication, study design, sample size and statistical methods, purpose/results/findings, limitations, conclusions/recommendations/navigation implications, role name, education/certification for role, role responsibilities, chronic space, and the initiation and termination of navigation in the disease trajectory.

Results

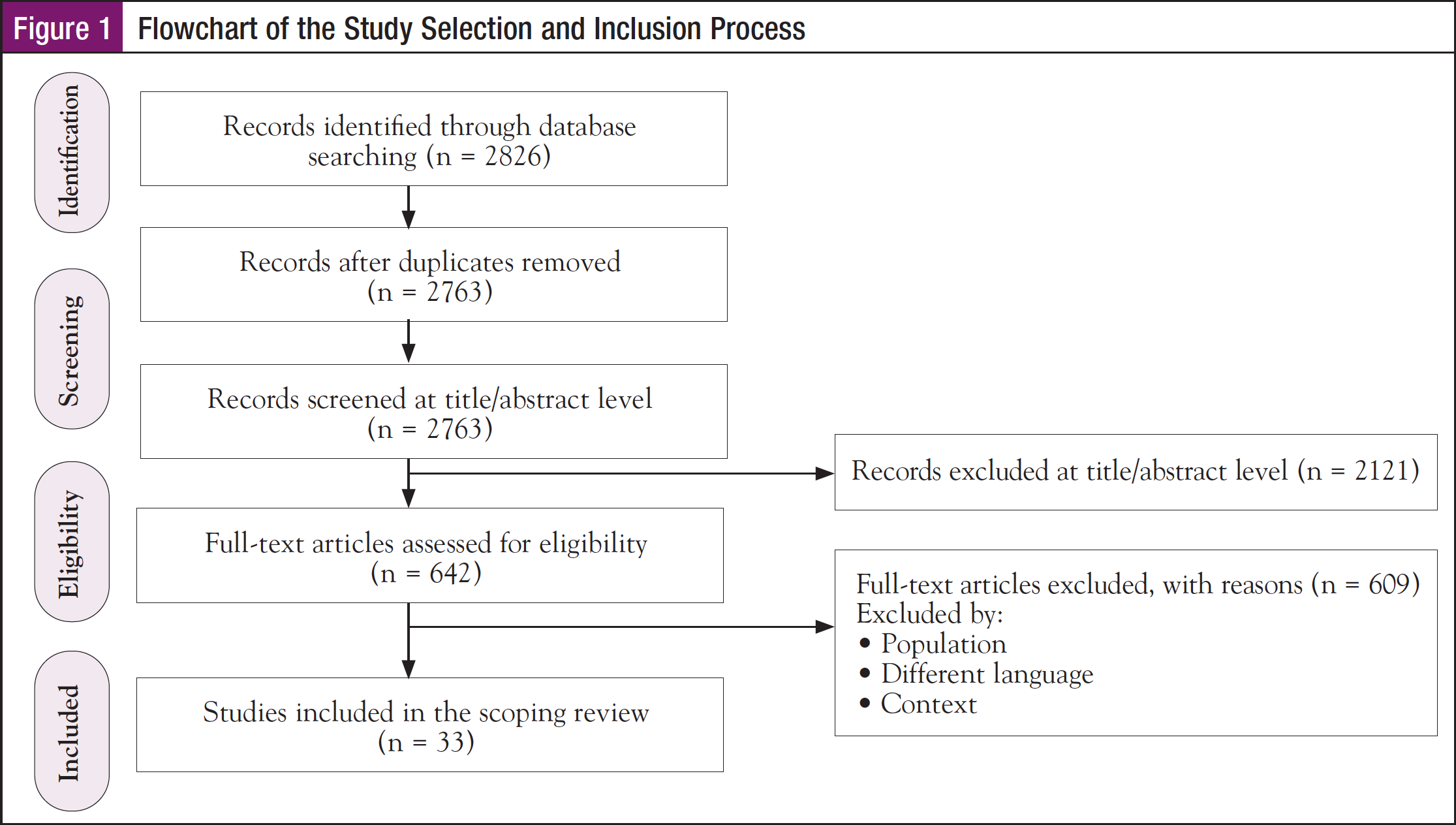

After removing duplicates, 2826 articles were screened for inclusion. A total of 642 articles met the inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts, and full-text publications were then reviewed. After review of full-text publications, 332 relevant articles were identified. Figure 1 shows the study selection process.

Navigator Term

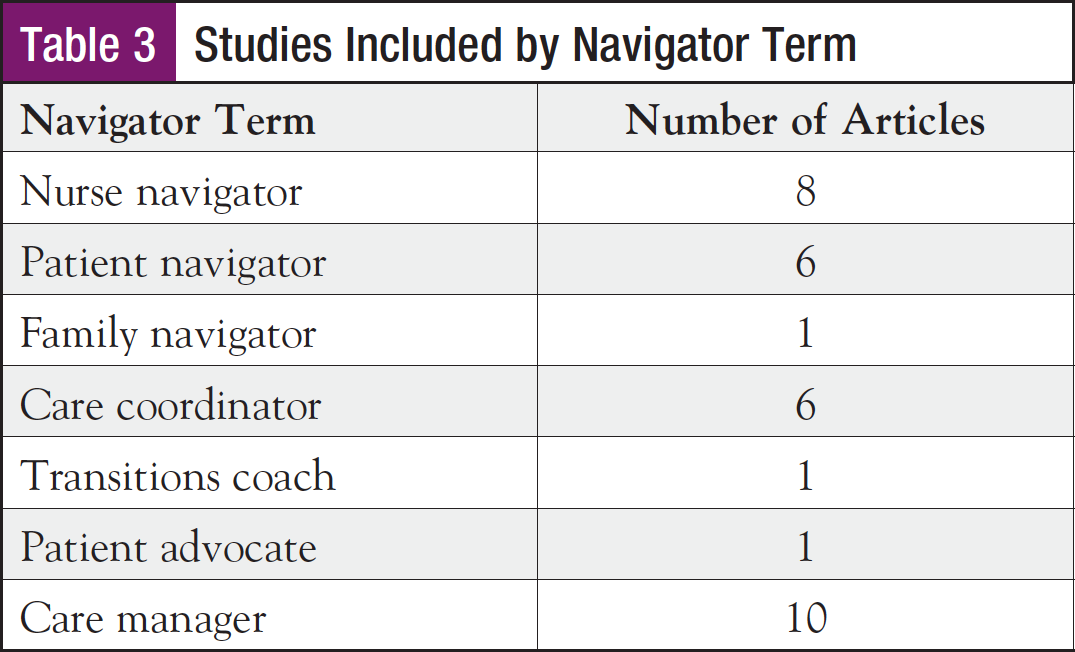

A total of 10 studies used the term care manager, 8 used nurse navigator, 6 each used patient navigator and care coordinator, and individual articles used family navigator, transitions coach, and patient advocate. Results from a recent AONN+ survey revealed that the most commonly used terms included navigator, care coordinator, case manager, care transitions coordinator, social worker, and community coordinator/community health worker.27 Table 3 shows the studies included in this scoping review by study design.

Year of Publication

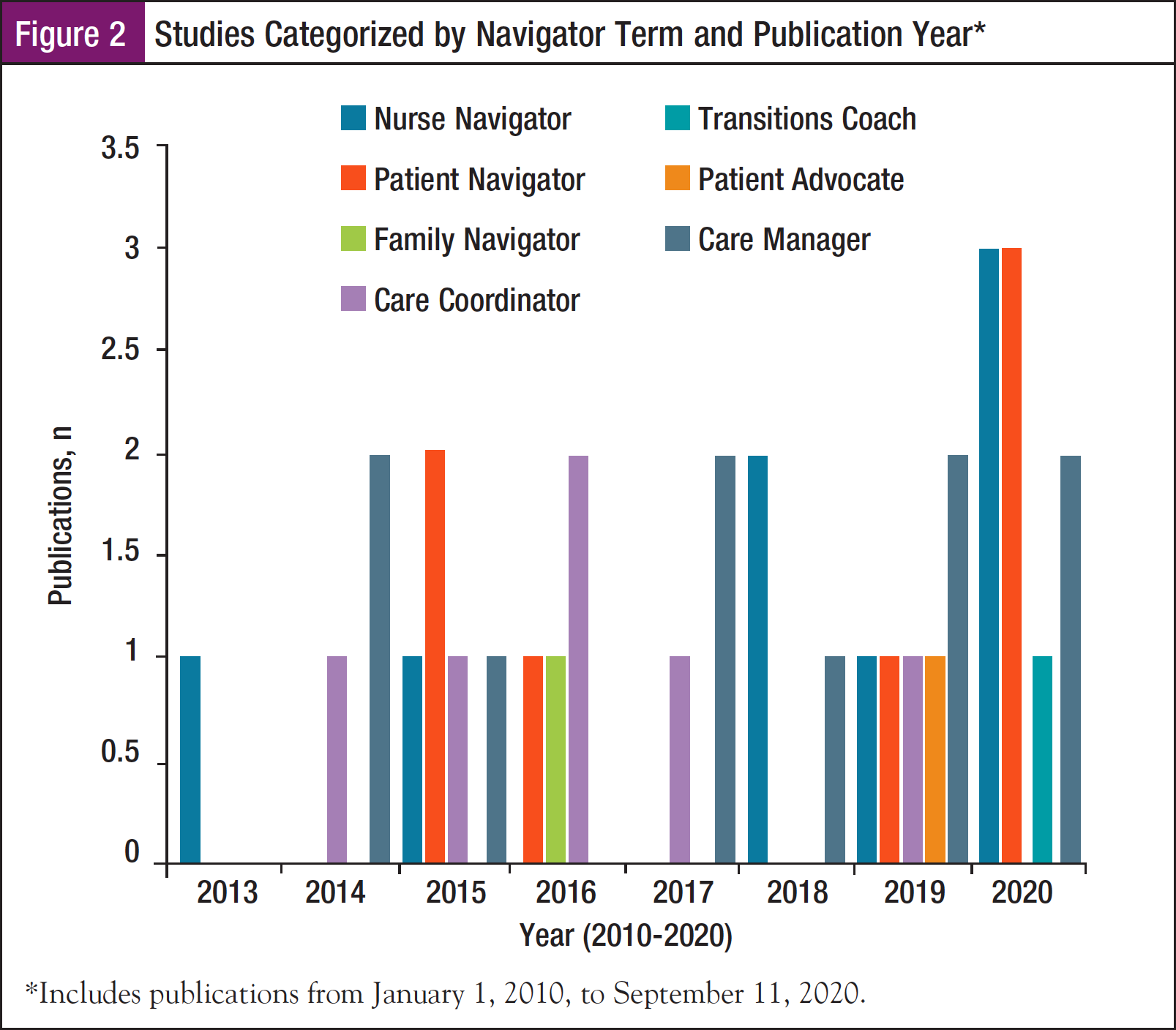

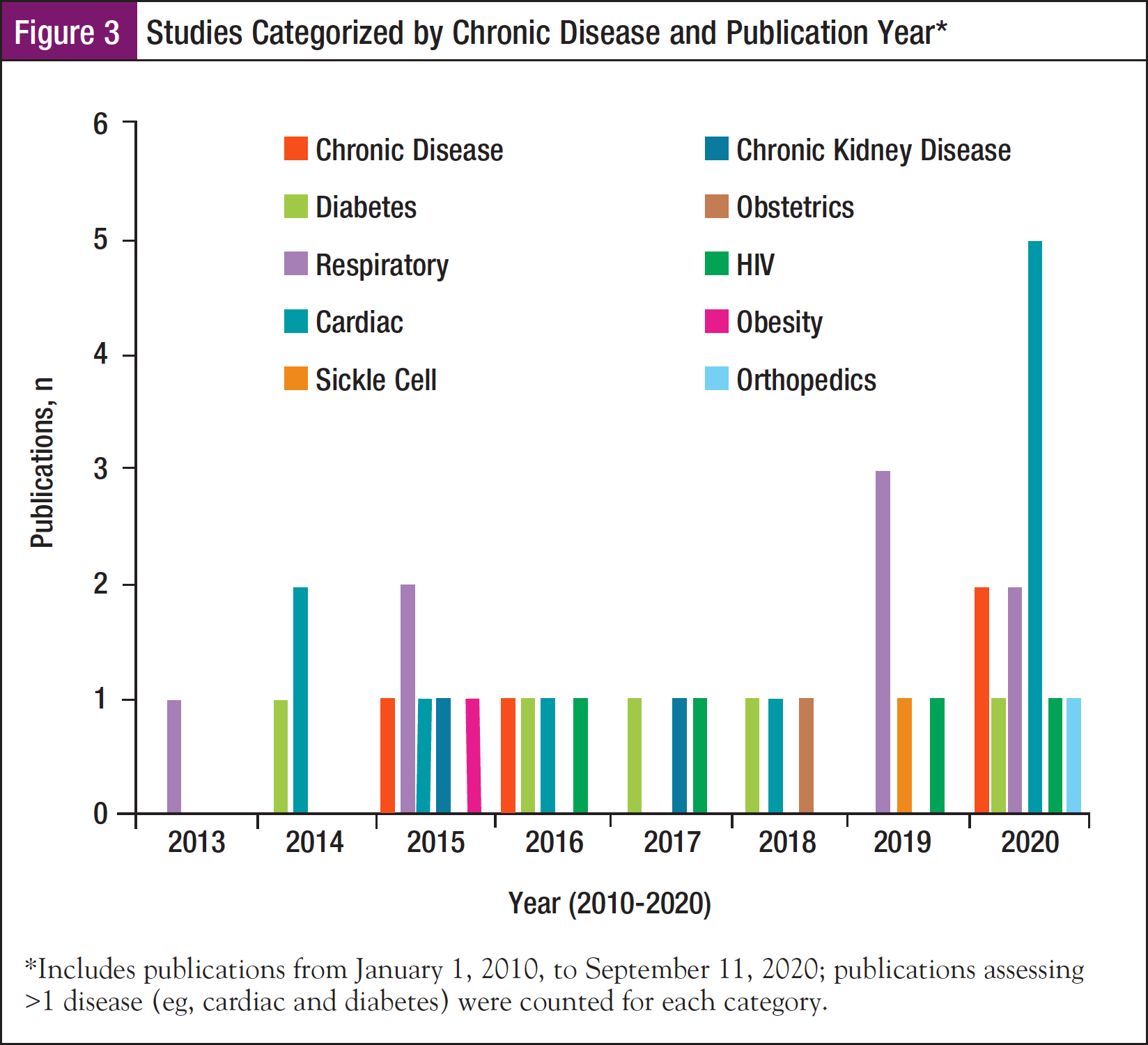

Included studies were published between January 1, 2010, and September 11, 2020. Figure 2 shows studies categorized by navigator term and publication year. Figure 3 shows studies categorized by chronic disease and publication year.

Nurse Navigator

We identified 8 articles using the term nurse navigator.28-35 Of these articles, 1 discussed orthopedics; 1, diabetes; 1, HIV; 4, cardiac disease; and 1, chronic disease in general. The largest number of articles was published in 2020 (n = 3), followed by 2018 (n = 2), and 2013, 2015, and 2019 (n = 1 each).

In a quality assurance study, a COPD nurse navigator was a master’s prepared clinical nurse specialist with extensive experience in pulmonary diseases working in a tertiary care hospital.30 The COPD nurse navigator saw patients with or without the physician depending on patient needs. She provided education to patients and their caregivers based on the Living Well with COPD program and helped patients cope with their illness through partnered disease management. She was available by telephone, pager, and e-mail to answer questions, assess the need for an action plan, or arrange for further assessment. Central to the interdisciplinary program is the nurse–physician partnership based on collaboration and communication. This relationship benefits patients by improving their access and interactions with the healthcare team. The nurse navigator facilitated timely transfers to other institutions, particularly an affiliated center specializing in pulmonary care and rehabilitation, where she continued to follow patients. She was available throughout transitions to address patients’ complex needs and promote continuity of care. She functioned as a single point person present across lines of care providing consistent access to the same healthcare provider and fostering communication within the interdisciplinary team.

According to one survey respondent, “I or one of my team members conducts a medical record review that covers a 10-year period to identify cause and effect analysis related to why the patient is a complex patient and utilizing the ER and inpatient hospital utilization. Next, we identify every person who has some degree of involvement with the patient in some way, what role they serve, when, where, and how often. The majority of the time, a point person who we identify to be the advocate for the patient may be a nurse practitioner, social worker, or someone else who is a medical professional.”

As part of a transitions of care (TOC) committee, nurse navigators counseled patients with heart failure on the discharge medications and answered any questions or addressed concerns regarding medications.31 The nurse navigator provided a more detailed lifestyle education than did the pharmacy team. In a study of implementing a stroke bundle framework, a nurse navigator reported directly to the bundle program manager, providing clinical oversight to assure safe and effective transitions of the patient to the next level of care throughout the 90-day period following hospital discharge.32 The navigator coordinated care and worked with physicians and all levels of acute and post-acute care providers, ensuring improved health status and positive patient outcomes while controlling healthcare expenditures across the continuum. This included but was not limited to inpatient care, rehabilitation, skilled and assisted living facilities, outpatient programs, and home health agencies. The stroke navigator met patients prior to discharge to set the stage for follow-up discharge phone calls.

In a study designed to determine if wireless oscillometric home blood pressure monitoring that integrates with smartphone technology improves blood pressure control among patients with new or existing uncontrolled hypertension, nurse navigators functioned to bridge communication between patients and provider.29

In a retrospective cohort analysis, the authors sought to evaluate linkage to care (LTC) in a non-urban hepatitis C virus (HCV) referral clinic with a nurse navigator model and identify disparities in LTC.34 Upon referral, the nurse coordinator directly contacts the referred patient by phone to schedule an appointment. The nurse coordinator will make multiple attempts to reach patients if calls are unanswered, and appointments are rescheduled in the case of no-shows. Referred patients are also provided the contact information for the clinic at the time of referral. The nurse coordinator provides education and counseling, both over the phone and at clinic appointments, as well as ensuring the appropriate paperwork is completed for medication approval. Medications may be obtained through private insurance, government insurance, or pharmaceutical patient assistance programs for uninsured patients. The nurse navigator assists patients in completing required financial screening, prior authorizations, and patient assistance program paperwork. FibroScans are performed within the clinic for staging of liver disease. A pharmacy-based team also assists with prior authorizations and provides telephone-based counseling related to HCV medications as well as potential interactions with patients’ other medications.

Abernethy provided an expert commentary of the role of nurse navigators in neonatal diabetes.28 After the infant has exhibited steady weight gain after glycemic stabilization on insulin and the caregiver training is completed, the goal becomes coordination of care for appropriate home management. The pharmacy in the local area is researched by the nurse navigator, who will inquire if there is a sterile hood available for safe and proper dilution to 10 units of insulin and order the diluent. The nurse navigator will schedule coordinated follow-up appointments with the primary care provider (PCP), endocrinologist, and certified pump trainer. The nurse navigator schedules time to meet with the family and come up with a book/manual for all education, contacts, appointments, and members of the team. The transition from hospital to home brings many new challenges for families managing their child’s diabetes. Parents have described feelings of fear and vulnerability as a result of leaving the hospital support system behind. This is the time when families need the support and encouragement of the nurse navigator so they can carry out the tasks of caring for their child and ensure that emergency plans and contacts are in place. The period after discharge, when the family will transition to their normal home environment with new tasks and a lot of medical equipment, is an important time. A 2-day follow-up after discharge is coordinated by the nurse navigator with the home health nurse. The success of this transition can be easily noted from the calmness and ease of task and care from the parents at this visit. All questions are answered, all appointments are discussed with the nurse, and all blood sugars are reviewed with the endocrinologist to see if any insulin adjustments are needed. As the nurse navigator, certain tasks had to be completed to ensure that all of the inpatient plans could be transitioned smoothly to the home setting. The insulin pump needs to be ready for use immediately without submitting to insurance for approval (which could take months). The nurse navigator must reach out to the specific pump company and obtain a loaner for immediate use. The nurse navigator will assist the family and endocrinologist to apply for the pump that has approval by their insurance company. The pharmacy must be notified to obtain diluent from the insulin company for proper, safe dilution of insulin. The initialization of the insulin pump was expedited significantly by the endocrinologist and nurse navigator, knowing that a team was established and each step of education for all was meticulously planned. To provide optimal family support, the home health nurses assigned to the infant for weight checks and blood sugar review need specialized training. The nurse navigator must coordinate the home health nurse and certified pump trainer to meet in the hospital and complete training. After staff and family education is completed, the insulin pump is initiated and the inpatient medical devices can be removed. After several days of insulin pump use with the family as primary caregivers, pump data are reviewed, and the family is now ready for discharge with their child on adequate insulin doses.

In a study designed to examine length of hospital stay and patient satisfaction following the implementation of an orthopedic surgery clinical nurse specialist-patient navigator, the mean length of stay was lower than the provincial mean.33 Participants were satisfied with the care provided by the navigator.

In an article focused on the effects of structured interdisciplinary bedside rounding (SIBR) in patients with chronic disease, nurse navigators rounded with the care team and made postdischarge follow-up phone calls to ensure seamless transition of patient care from hospital to home.35 In addition, the bridge nurse navigator coached SIBR team members during the initial implementation period, recorded the time taken to perform SIBR for each patient, and provided feedback to the team members in real time to standardize the process and alleviate individual variability during SIBR rounds. SIBR did not reduce length of stay and 30-day readmissions, but it had a significant impact on 7-day readmissions. The authors suggest that SIBR merits further study for improving hospital care and patient outcomes.

Patient Navigator

We identified 6 articles using the term patient navigator.36-41 The majority of the articles were published in 2020 (n = 3), followed by 2015 (n = 2), and 2016 (n = 1). Of these articles, 1 discussed obesity; 1, HIV; 1, diabetes; 1, chronic kidney disease (CKD); 1, respiratory disease, and 1, cardiac disease.

As part of a quality project to improve care for high-risk COPD patients admitted with an exacerbation, patient navigators called patients within 1 week of discharge to ensure that they had an appointment and medications.37 This study supports the concept that care coordination may be an area of opportunity for improving care for high-risk COPD patients, who frequently have significant comorbid disease and psychosocial burdens.

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) Patient Navigator Program, a 2-year quality improvement campaign, sought to assess the impact of transition care interventions on 30-day readmission rates for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or heart failure (HF) at 35 hospitals.40 Many hospitals used electronic data capture (electronic health record [EHR] or admission database information) or a patient navigator (care coordinator) to identify patients hospitalized with AMI and HF. Each hospital determined its own method for assessing the risk of readmission, which may have involved the use of a published tool from the literature, previous local assessment of high-risk factors, the use of a patient navigator, or a combination of multiple methods. The ACC quality leaders promoted improvement in the transition care measures through an online dashboard, webinars, a listserv, in-person educational forums, and one-on-one support.

A CKD patient navigator program was designed to help coordinate care, address system barriers, and educate/motivate patients.38 Two CKD patient navigators will be responsible for navigating CKD patients enrolled in a clinical trial. The patient navigators have undergone training in general patient navigation, specific CKD education through directed readings and clinical shadowing, as well as EHR and other patient-related privacy and research training. Responsibilities include addressing barriers related to assessment, compliance/adherence, consultation, education of patient/family, financial applications, information, insurance inquiry, referral to financial counselors, other referral, community resources, and transportation.

In a study designed to test the feasibility and acceptability of telephone-based nonprofessional patient navigation to promote linkages between the PCP office and community programs for patients with or at risk for diabetes, patient navigators provided feedback to providers, patients, and community programs and maintained a patient navigation tracking database using a web-based client relationship management system.39 Patient navigators were primarily responsible for proactively connecting patients with community-based programs, following patients after referral, and providing information and encouragement. Patient navigators were not responsible for health education or for providing emotional support; rather, they encouraged patients to use appropriate community programs where these services are typically provided.

LA Links used a surveillance system to identify people living with HIV who were not in regular healthcare and connected them to a patient navigator.36 During the intervention period, persons who lapsed from care were 17% more likely to reengage in care than persons in the comparison group, and persons newly diagnosed during the intervention period were 56% more likely to link to care. Despite potential limitations, the results provided compelling evidence that support can help people living with HIV obtain care. An intervention using surveillance data to identify and contact out-of-care people coupled with navigation services and treatment adherence counseling increases the likelihood that newly diagnosed people living with HIV will link to care and previously diagnosed people will reengage in care.

A home-based intervention was designed to address childhood obesity and be delivered by patient navigators.41 At the beginning of the intervention, the patient navigator contacted a cohort of previously recruited families to schedule the first home visit. The first home visit was aimed at creating a positive rapport between the caregiver and the patient navigator and to set program expectations and goals. At this visit, the patient navigator set lifestyle change and weight goals with families. The home-based intervention links to clinical care through update/outcome letters and program impact assessments shared with medical providers. By informing PCPs about a child’s program accomplishments and challenges, the clinician may personalize messages to families during subsequent clinical visits.

Family Navigator

We identified 1 article using the term family navigator (FN).42 This article was published in 2016 and focused on chronic disease in general. In a pilot randomized controlled trial of the FN, a distinct nursing role to address family members’ unmet communication needs early in an ICU stay, the FN was an experienced ICU registered nurse who underwent a 2-week training period.42 This included shadowing staff members (nurse manager, clinical director, social worker, and chaplain) to learn how their roles would complement each other, review of the research protocol, study materials, and related literature. The FN also met regularly with the principal investigator and nurse researcher to review materials and refine the role and underwent a half-day training session based on the VitalTalk45 method, led by a trained facilitator. The FN contacted the surrogate decision makers (SDMs) 5 days per week. The FN participated in daily ICU rounds and completed a structured form to guide daily family communication, including patient status, goals of care, and clinical plan for the day. A goal of communication with family SDMs 90% of weekdays was established. The physician, social worker, or other clinicians were encouraged to maintain their usual level of contact with families. The FN contacted the SDM at 3 days and at 2 weeks after ICU discharge to assess for any unmet informational or emotional needs and responded with referrals to appropriate hospital resources.

Care Coordinator

We identified 6 articles using the term care coordinator.43-48 The majority of articles were published in 2016 (n = 2), followed by 1 article each in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2019. Overall, 2 articles focused on respiratory disease, 1 on HIV, 1 on diabetes, and 2 on cardiac disease.

A cross-sectional clinical study was designed to investigate the effect of a care coordinator on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patient satisfaction and quality of life.45 In the high-coordinator use clinic, the coordinator was involved with patient management, education, treatment, research, and administration, whereas the coordinator only assisted with treatment-related tasks in the low-coordinator use clinic. Reliance on a coordinator during routine management of IPF patients may improve patient satisfaction, save physician time, and lead to annual cost savings. Care coordination for children/young adults with asthma could focus on adherence to guidelines, access to medications and specialists, asthma action/care plans, home care coordination, and environmental/social supports.46 Referral management and self/family care represented the largest focus of care coordination. This is important in designing practice asthma programs, engaging team members (referral coordinators), and planning practice-based asthma care coordination.

In a study focused on the impact of arrhythmia care coordinators on their patients’ levels of anxiety and depression, hospital readmissions, and costs to the National Health Service, care coordinators were involved in areas related to preparation, support, referral, assessment, audit, inpatient support, developing, management, and ongoing provision of education/training.47 All of the appointees were registered nurses. In arrhythmia specialist nurse sites, readmission rates were reduced by half. After deducting the cost of the arrhythmia care coordinators and their support, the estimated annual saving was £29,357 (approximately $39,796) per arrhythmia care coordinator. In a study designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a stroke-specific follow-up care model on quality of life for patients being discharged home and their caregivers, stroke care coordinators (SCCs) were nurses from home care services specializing in stroke.44 The SCC visited the stroke patients at home 1 to 2 weeks and 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after discharge. More home visits were offered as needed. During each home visit, the SCC administered a structured assessment tool (which was developed for the study) to assess a broad spectrum of stroke-related problems (activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, social activity, cognition, communication, psycho-emotion, fatigue, secondary prevention, medical consumption, medical condition, caregivers’ strain, and provision of information). Based on these assessments, the SCC provided suitable follow-up care during the home visits, such as giving information and advice or referring the patient to physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and other healthcare professionals. After each home visit the SCC sent a written report to the patient’s PCP. The SCC could consult a multidisciplinary team from the nursing home (physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, social worker, and psychologist) for advice as needed.

According to a survey respondent, “It depends on the part of the country and what resources they have whether advanced practice nurses or RNs are utilized in these roles. For example, a countywide collaborative is run by a PhD social worker, a spiritual caregiver, an MD, and the mayor. That’s the most different utilization of human resources we have created. Most of the programs go deeper and have a bigger impact if there’s an advanced practice nurse or advanced practice social worker leading them.”

A study was designed to evaluate diabetes control, as measured by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) improvements among African American and Hispanic patients receiving conventional clinical treatment combined with a bilingual diabetes educator using culturally and linguistically appropriate educational materials.48 Care coordinators’ responsibilities included the following:

- Outreach to African American and Hispanic patients with an A1c ≥8% with a focus on identifying and closing gaps or barriers to care and helping patients develop healthcare goals

- Outreach to all specialists involved in patient care by obtaining test results and consulting notes and compiling them for PCPs to review and use to update the patient’s EHR

- Engaging patients in scheduling office visits, obtaining their own laboratory blood test results, and working with physicians to develop needs-based care plans

- Providing patients with educational materials or scheduling diabetes education sessions

- Connecting with patients for previsit and postvisit planning, including reminders for patient appointments and postappointment follow-ups to ensure patients had understood physician recommendations

- Communicating with patients through telephone calls and a “virtual patient portal” system that allows for secure Internet discussions of laboratory reports, appointment schedules, or plans of care

- Educating patients and their families about prevention and healthcare management, which include the use of motivational interviewing techniques

- Assisting patients with prescription medication regimens and consulting with their PCPs on alternative medications when patients could not afford copays.

The Expanded Testing and Linkage to Care (X-TLC) program was conducted with the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) and 9 community partner sites to expand routine HIV testing to high-prevalence communities with disproportionately affected populations.43 Each week, the UCM linkage-to-care coordinator received an automated report of all patients tested for HIV. The coordinator reviewed the list to discuss active linkage to care for those with positive test results and supplemental or repeat testing for patients with indeterminate results. Coordinators at other sites regularly reviewed their own test results and linked patients to care. Although ordering providers were encouraged to discuss results with patients, the linkage-to-care coordinator at UCM notified HIV-positive patients if the site personnel were uncomfortable with test notification or unable to make contact.

Transitions Coach

We identified 1 article using the term transitions coach.49 This article was published in 2020 and focused on older adults with chronic disease. A review article, it described common models for posthospital transition and the Mayo Clinic model for care transition.49 Results from meta-analyses have contributed to the identification of the most impactful program elements for decreasing 30-day hospital readmissions, such as multidisciplinary and bundled approaches. Self-empowerment for caregivers and patients alike also contributes to successful care teams. In a model introduced by Mary Naylor, patient care is delivered by an advanced practice provider for a set period of time. In a model introduced by Eric Coleman, the patient receives guidance from a transitions coach, who can be a trained volunteer, a registered nurse, or a social worker. The Mayo Clinic Care Transitions program has encompassed a 7-year experience, using the services of an advanced practice provider. The Mayo Clinic Care Transitions model has contributed to a 20.1% decrease in 30-day readmission compared with 12.4% in the control group. However, no difference was observed between groups at 180 days. Among patients who experience the highest deciles of cost, care transitions program participation resulted in a significant reduction of overall cost by $2700. A model tested by Parry and Coleman used coaches with nursing backgrounds to facilitate continuity and also ease the discharge transition among a targeted Medicare population. The coaches conducted a postdischarge home visit within 2 to 3 days. The patients set their own patient-centered goals. The visits specifically focused on equipping both patients and caregivers with the skills needed to assume more active roles in the care process, as well as communication skills and promotion of continuity in all care settings. The team also incorporated multiple follow-up phone calls to encourage self-management.

Patient Advocate

We identified 1 article using the term patient advocate (PA).50 This article was published in 2019 and focused on respiratory disease. In an ongoing study, a new clinical role adapted from a patient navigator called the PA met with patients before medical visits, attended appointments, and afterward reviewed provider instructions.50 This qualitative analysis examines the perspectives of PAs and providers regarding their experiences with patients to understand how a PA can help patients and providers achieve better asthma control. PAs are recent college graduates with an interest in healthcare careers, research experience, and working with patients. At least 2 PAs are fluent in Spanish, and Spanish-speaking patients were matched with a Spanish-speaking PA. PAs help patients prepare for medical visits, attend medical visits with patients, review provider instructions, perform check-in calls, and assist with other health system navigation tasks. The PAs and the providers cited numerous ways PAs can help to improve patient–provider mutual understanding.

Care Manager

We identified 10 articles using the term care manager.51-60 The majority of the articles were published in 2020 (n = 3); followed by 2014, 2017, and 2019 (n = 2 each); and 1 article was published in 2016. Overall, 2 articles focused on respiratory disease, 1 on sickle cell, 1 on CKD, 1 on obstetrics, 1 on HIV, 1 on diabetes, 3 on cardiac disease, and 1 on chronic disease in general.

In a review article focused on collaborative care for patients with respiratory disease, care managers could include nurses, social workers, or psychologists.60 Care managers were responsible for monitoring symptoms, brief behavioral interventions, and other activities, including case review with the psychiatric care provider. The psychiatric care provider is not expected to be on-site but will review cases with the care manager, who will communicate recommendations back to the PCP. A study was designed to assess the contributions of care management as perceived by care managers themselves.54 Responsibilities of care managers were to ensure that patients follow up with their PCP and contact the PCP on behalf of patients; educate patients; use IT health applications; perform medication reconciliation; focus on specific patients and build relationships; support and help clinicians; and build trust with clinicians over time. Inpatient care managers believe that (1) ensuring PCP follow-up, (2) coordinating appropriate services, (3) providing patient education, and (4) ensuring accurate medication reconciliation have the greatest impact on patient clinical outcomes. In contrast, outpatient and TOC managers believe that (1) teaching patients the signs and symptoms of acute exacerbations, and (2) building effective relationships with patients improve patient outcomes most. Some care management activities were perceived to have greater impact on patients with certain conditions (eg, outpatient and TOC managers saw effective relationships as having more impact on patients with COPD). All care managers believed that relationships with patients have the greatest impact on patient satisfaction, whereas the support they provide clinicians has the greatest impact on clinician satisfaction.

According to one survey respondent, “I’m very involved in educating the nurses that we recruit to be part of this to really be able to do the role. I’m involved in ongoing support of them, so we do case conferences. I lead these case conferences; we do root cause analysis. If the patient has an ER visit or a fall or readmission, we want to say what happened, and we really dig down into saying what was the real root cause of that. We also did root cause analysis if something great happened. We prevented a hospitalization, we figured out a way to get a patient who never had been able to take their meds correctly to really turn things around, and we learned from that. We learned from the positive as well as how to correct the negative.”

In a pilot study designed to test the feasibility, acceptance, and effect of a 6-month blended collaborative care intervention in Germany, care managers collected sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, family status, social status, and educational level) by patient self-report and administered the assessment battery, which is also administered at 6 and 12 months of follow-up.53 Study care managers (assistant physician, psychologist, or study nurse) were trained in motivational interviewing and problem-solving therapy before delivering the 6-month intervention. A cluster randomized trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a disease and care management model in cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care patients with hypertension.55 All participating nurses, who acted as care managers, attended education and training sessions on clinical recommendations, coaching techniques, and dedicated software system use.

In a study designed to evaluate an investigational in-home telemetry device for improving glucose and blood pressure control over 6 months for patients with type 2 diabetes, care managers responded (via telephone or other method, including the telemetry device) as appropriate based on previously described target goals.58 The care managers also used the telemetry device to send/deliver appropriate educational information or messages (as per standard diabetes care management protocols).

An off-site HIV depression care team, including a psychiatrist, a depression care manager, and a clinical pharmacist, provided collaborative care using a stepped-care model of treatment and made recommendations to providers through the EHR system.56 The care manager delivered care management to HIV patients through phone calls, performing routine assessments and providing counseling in self-management and problem-solving. The care manager documented all calls in each patient’s EHR.

In a study designed to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of perinatal depression treatment integrated into a rural obstetric setting, care managers were trained in an engagement session, problem-solving therapy, text messaging protocols, and general information on perinatal mental health and pharmacotherapy.51 Encounters occurred in the clinic or in the patient’s home. The first encounter was an engagement interview designed to address practical, psychological, and cultural barriers to care. Subsequent sessions were 6 to 8 weekly sessions of problem-solving therapy if chosen by the patient. Between sessions, care managers communicated with patients via text messaging.

In a randomized study of patients with late-stage CKD, a care management intervention involved nurse care manager coordination aided by the use of a disease-based informatics system for monitoring patients’ clinical status, enhancing CKD education, and facilitating preparation for end-stage kidney disease. The comparison control group received usual late-stage CKD care alone.57 The initial intervention consists of a visit by the nurse care manager to the patient’s home. The nurse meets with the patient and key caregivers. Health-literate patient-centered education on CKD, self-management support, and various treatment options are provided. Motivational interviewing is used to elicit comprehension and produce meaningful communication exchanges. Other essential elements of home visits are dietary education, medication reconciliation, and home safety assessment. Dietary education is primarily focused on consistently maintaining low sodium intake and providing greater skill in reading food labels. A visit to the patient’s kitchen helps the nurse assess the types of food the patient has available and offers an opportunity for further discussion on nutrition. Medication reconciliation consists of review of the patient’s medicine bottles to determine which agents are being taken. This information is reconciled to the medication list from the nephrology practice. Home safety is evaluated with a focus on factors that create risk for falls. Following the home visit, the nurse care manager and nephrologist work to develop a plan of care that is goal-specific and patient-centered. The nurse subsequently follows up with patients monthly by telephone or more frequently as needed. An increase in body weight and issues related to preparation for end-stage kidney disease treatment may drive more frequent calls to patients, whereas any changed symptoms are a main reason for calls from patients. Any changes in diuretic dose or other treatment as a result of symptoms or weight changes were made by the patient’s nephrologist after discussion with the nurse care manager.

According to a survey respondent, “Symptom management is absolutely core if you want to keep people out of the hospital. People get hospitalized over symptoms. If you keep the symptoms under control, then they’re going to be able to do things effectively. You’re helping them see what are the early stages of getting into trouble so they’re not calling you when there is no other option but the ER. They’re calling you when you can do some interventions before things get worse.”

In a project designed to describe the implementation and evaluation of a care management referral program from emergency departments to care management services for patients with sickle cell disease, more than 900 referrals were received in 3.5 years.59 Pain was the most common reason for referral. An increase in care management intensity was observed over time. All levels of care management intensity saw an increase in the number of patients. Patients with ongoing care needs were identified, and there was an increase in the intensity of outpatient care management services delivered.

According to a survey respondent, “We now have a grant that is helping us to roll this model out into 4 health systems around the country. Then COVID hit. We would’ve been up and running and radically rolling with data collection by now, but it’s gotten a slow start. What we’re doing is we are working with those hospitals to truly implement the model in their health systems.”

In a study designed to assess the feasibility of a patient-centered complex intervention for multimorbidity based on general practice in collaboration with community healthcare centers and outpatient clinics, the nurse care manager coordinated activities in primary and secondary healthcare sectors to support integrated care.52 All planned activities took place within a 6-month intervention period that ended with a second extended general practitioner consultation focusing on whether the patients’ care goals were fulfilled. Patients had diagnoses of 2 or more of 3 chronic conditions (diabetes, COPD, and chronic heart conditions), and a hospital contact during the previous year.

According to a survey respondent, “Without working with the community, nothing really can be accomplished for these chronic illness patients long-term.” She coined the phrase, ‘Trying to create an accountable community of health.’ “We have worked with oncology nurse navigators for quite some time, handling the comorbid conditions, and they have learned what impact cancer treatments can have on chronic illnesses, such as a spike in blood sugars for cancer patients receiving steroids during their chemotherapy treatments.

“We were invited by the faculty to help reduce length of stay and reduce ER visits and unplanned clinic visits for surgical patients, gynecological patients, and now also orthopedic patients. In our designed programs, case management and transitional care are joined. Almost everyone we discharge goes home with something, some sort of plan, because we recognize that there are a whole lot of people who are not going to do well.”

Discussion

Limitations

This scoping review identified 7 main terms used in publications regarding chronic disease navigation. Survey results have suggested that physicians or other members of the healthcare team may function as a chronic disease navigator without specifically identifying as such.

This scoping review was limited based on the inclusion of studies only published in English in the past decade. Articles published in other languages or studies published more than 10 years ago may have provided important information for this review.

Key Findings

Overall, our search strategy extracted a total of 2826 records, from which 642 full-text articles were evaluated, and a total of 33 relevant studies were included in this scoping review. The most commonly used navigator terms were care manager and nurse navigator. We found 10 articles focused on cardiac disease and 8 articles focused on respiratory disease. The current literature does not provide consistent information regarding navigator terminology, or navigator education and responsibilities.

Implications for Practice

The findings from these studies will help inform trends in navigation practice within the chronic disease space.

Conclusions

The results of this scoping review highlighted the variety of navigator terms used within the chronic disease space. These findings also demonstrate a continuing need for research evaluating the impact of chronic disease navigators among the many chronic diseases affecting patients in the United States. Addressing these gaps will provide a wider evidence base for understanding trends in navigation practice within the chronic disease space.

Additionally, the information yielded from the surveys and the key opinion leader one-on-one interviews confirmed the growing need for chronic disease navigators and that there is already a professional population of such nurse navigators working with patients living with various chronic diseases (Appendix II).

There is an absence of a professional organization for chronic disease and complex care navigators that needs to be filled for these professionals to have opportunities to network with one another, advance their knowledge of specific chronic disease diagnoses and treatments that are constantly changing, and advance their knowledge within the navigation space.

Acknowledgment

Medical writing support was provided by Erin Burns, PhD, MSPH, under direction of the authors.

References

- AARP. Chronic Conditions Among Older Americans. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/beyond_50_hcr_conditions.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Fried LP. America’s Health and Health Care Depend on Preventing Chronic Disease. HuffPost. www.huffpost.com/entry/americas-health-and-healthcare-depends-on-preventing_b_58c0649de4b070e55af9eade#:~:text=Eighty%2Dsix%20percent%20of%20all,preventing%20these%20conditions%20is%20high. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Tinker A. How to Improve Patient Outcomes for Chronic Diseases and Comorbidities. Health Catalyst. www.healthcatalyst.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/How-to-Improve-Patient-Outcomes.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Comlossy M. Chronic Disease Prevention and Management. National Conference of State Legislatures; Denver, CO, USA. https://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/chronicdtk13.pdf. 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.Pdf. 2020. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- Anderson G. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2010/01/chronic-care.html. 2010.

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68, no 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Disease Facts. www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm#:~:text=Heart%20disease%20is%20the%20leading,1%20in%20every%204%20deaths. Last reviewed September 8, 2020. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. COPD National Action Plan. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/COPD-national-action-plan. Last updated February 9, 2021. Accessed February 14, 2021.

- Thomas J. COPD: Facts, Statistics, and You. Healthline Media. www.healthline.com/health/copd/facts-statistics-infographic. Updated July 2, 2020. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basics About COPD. www.cdc.gov/copd/basics-about.html. Reviewed July 19, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- Sullivan J, Pravosud V, Mannino DM, et al. National and state estimates of COPD morbidity and mortality – United States, 2014-2015. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5:324-333.

- Parker VA, Lemak CH. Navigating patient navigation: crossing health services research and clinical boundaries. Adv Health Care Manag. 2011; 11:149-183.

- Pedersen A, Hack TF. Pilots of oncology health care: a concept analysis of the patient navigator role. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:55-60.

- Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113:1999-2010.

- Freeman HP. The history, principles, and future of patient navigation: commentary. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:72-75.

- Walkinshaw E. Patient navigators becoming the norm in Canada. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1109-E1110.

- Thom DH, Ghorob A, Hessler D, et al. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:137-144.

- Lasser KE, Kenst KS, Quintiliani LM, et al. Patient navigation to promote smoking cessation among low-income primary care patients: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2013;12:374-390.

- Quintiliani LM, Russinova ZL, Bloch PP, et al. Patient navigation and financial incentives to promote smoking cessation in an underserved primary care population: a randomized controlled trial protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt B):449-457.

- Enard KR, Nevarez L, Hernandez M, et al. Patient navigation to increase colorectal cancer screening among Latino Medicare enrollees: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:1351-1359.

- Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Kutner JS. Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1023-1028.

- Shlay JC, Barber B, Mickiewicz T, et al. Reducing cardiovascular disease risk using patient navigators, Denver, Colorado, 2007–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A143.

- Goff SL, Pekow PS, White KO, et al. IDEAS for a healthy baby—reducing disparities in use of publicly reported quality data: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:244.

- Scott LB, Gravely S, Sexton TR, et al. Examining the effect of a patient navigation intervention on outpatient cardiac rehabilitation awareness and enrollment. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33:281-291.

- Darnell JS. Navigators and assisters: two case management roles for social workers in the Affordable Care Act. Health Soc Work. 2013;38:123-126.

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators. Data on file.

- Abernethy SH. Neonatal diabetes: nurse navigator role. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:145-146.

- Ciemins EL, Arora A, Coombs NC, et al. Improving blood pressure control using smart technology. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:222-228.

- Dajczman E, Robitaille C, Ernst P, et al. Integrated interdisciplinary care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease reduces emergency department visits, admissions and costs: a quality assurance study. Can Respir J. 2013;20:351-356.

- Gunadi S, Upfield S, Pham ND, et al. Development of a collaborative transitions-of-care program for heart failure patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:1147-1152.

- Gzesh D, Murphy DA, Peiritsch H, MacCracken T. Benefit of a stroke management program. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23:482-486.

- Sawhney M, Teng L, Jussaume L, et al. The impact of patient navigation on length of hospital stay and satisfaction in patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2021;41:100799.

- Sherbuk JE, McManus KA, Kemp Knick T, et al. Disparities in hepatitis C linkage to care in the direct acting antiviral era: findings from a referral clinic with an embedded nurse navigator model. Front Public Health. 2019;7:362.

- Sunkara PR, Islam T, Bose A, et al. Impact of structured interdisciplinary bedside rounding on patient outcomes at a large academic health centre. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:569-575.

- Anderson S, Henley C, Lass K, et al. Improving engagement in HIV care using a data-to-care and patient navigation system in Louisiana, United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020;31:553-565.

- Gay E, Desai S, McNeil D. A multidisciplinary intervention to improve care for high-risk COPD patients. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35:231-235.

- Jolly SE, Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, et al. Development of a chronic kidney disease patient navigator program. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:69.

- Loskutova NY, Tsai AG, Fisher EB, et al. Patient navigators connecting patients to community resources to improve diabetes outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:78-89.

- Wu CM, Albert NM, Gluckman TJ, et al. Facilitating the identification of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure and the assessment of their readmission risk through the patient navigator program. Am Heart J. 2020;224:77-84.

- Yun L, Boles RE, Haemer MA, et al. A randomized, home-based, childhood obesity intervention delivered by patient navigators. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:506.

- Torke AM, Wocial LD, Johns SA, et al. The family navigator: a pilot intervention to support intensive care unit family surrogates. Am J Crit Care. 2016;25:498-507.

- Bares S, Eavou R, Bertozzi-Villa C, et al. Expanded HIV testing and linkage to care: conventional vs. point-of-care testing and assignment of patient notification and linkage to care to an HIV care program. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(Suppl 1):107-120.

- Fens M, van Heugten CM, Beusmans G, et al. Effect of a stroke-specific follow-up care model on the quality of life of stroke patients and caregivers: a controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:7-15.

- Hambly N, Goodwin S, Aziz-Ur-Rehman A, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patient satisfaction and quality of life with a care coordinator. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:5547-5556.

- Hamburger R, Berhane Z, Gatto M, et al. Evaluation of a statewide medical home program on children and young adults with asthma. J Asthma. 2015;52:940-948.

- Ismail H, Coulton S. Arrhythmia care co-ordinators: their impact on anxiety and depression, readmissions and health service costs. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15:355-362.

- Rawlins WS, Toscano-Garand MA, Graham G. Diabetes management with a care coordinator improves glucose control in African Americans and Hispanics. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:22.

- Takahashi PY, Leppin AL, Hanson GJ. Hospital to community transitions for older adults: an update for the practicing clinician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:2253-2262.

- Localio AM, Black HL, Park H, et al. Filling the patient–provider knowledge gap: a patient advocate to address asthma care and self-management barriers. J Asthma. 2019;56:1027-1036.

- Bhat A, Reed S, Mao J, et al. Delivering perinatal depression care in a rural obstetric setting: a mixed methods study of feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;39:273-280.

- Birke H, Jacobsen R, Jønsson AB, et al. A complex intervention for multimorbidity in primary care: a feasibility study. J Comorb. 2020;10: 2235042X20935312.

- Bosselmann L, Fangauf SV, Herbeck Belnap B, et al. Blended collaborative care in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease improves risk factor control: results of a randomised feasibility study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020; 19:134-141.

- Carayon P, Hundt AS, Hoonakker P, et al. Perceived impact of care managers’ work on patient and clinician outcomes. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2015; 3:158-167.

- Deales A, Fratini M, Romano S, et al. Care manager to control cardiovascular risk factors in primary care: the Raffaello cluster randomized trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:563-571.

- Drummond KL, Painter JT, Curran GM, et al. HIV patient and provider feedback on a telehealth collaborative care for depression intervention. AIDS Care. 2017;29:290-298.

- Fishbane S, Agoritsas S, Bellucci A, et al. Augmented nurse care management in CKD stages 4 to 5: a randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017; 70:498-505.

- Pressman AR, Kinoshita L, Kirk S, et al. A novel telemonitoring device for improving diabetes control: protocol and results from a randomized clinical trial. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:109-114.

- Rushton S, Murray D, Talley C, et al. Implementation of an emergency department screening and care management referral process for patients with sickle cell disease. Prof Case Manag. 2019;24:240-248.

- Yohannes AM, Newman M, Kunik ME. Psychiatric collaborative care for patients with respiratory disease. Chest. 2019;155:1288-1295.

Appendix I: Search Strategy

CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

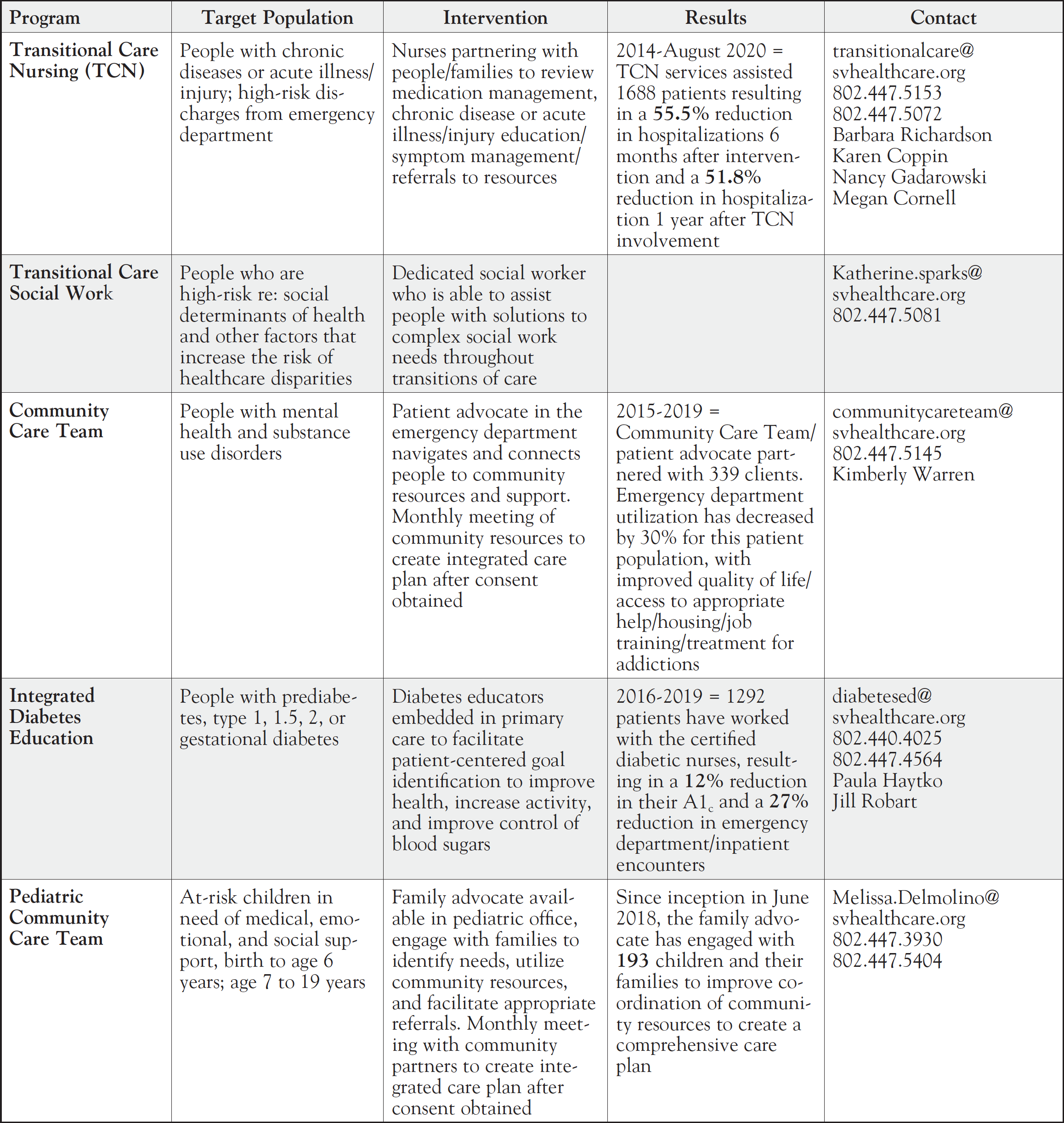

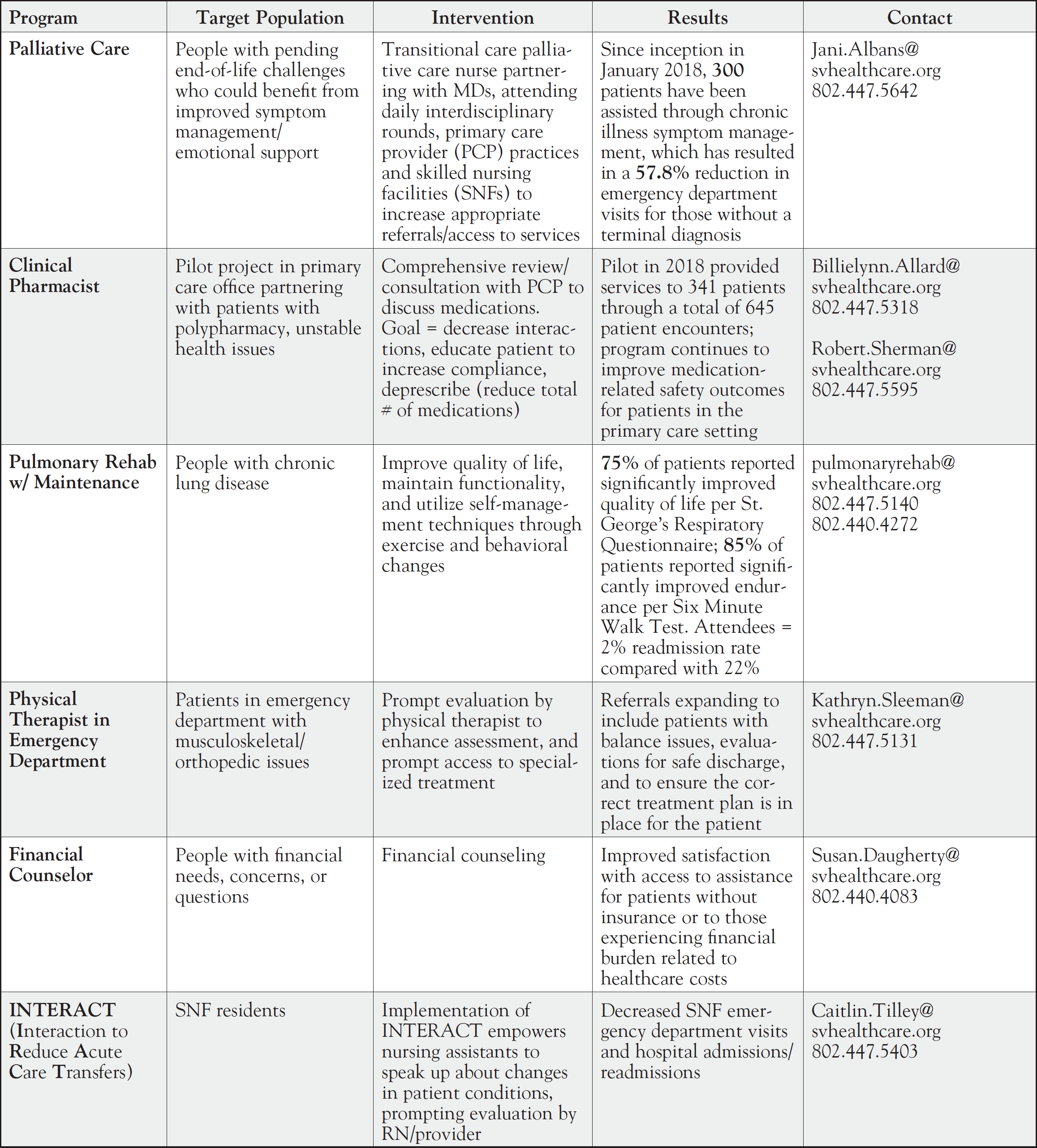

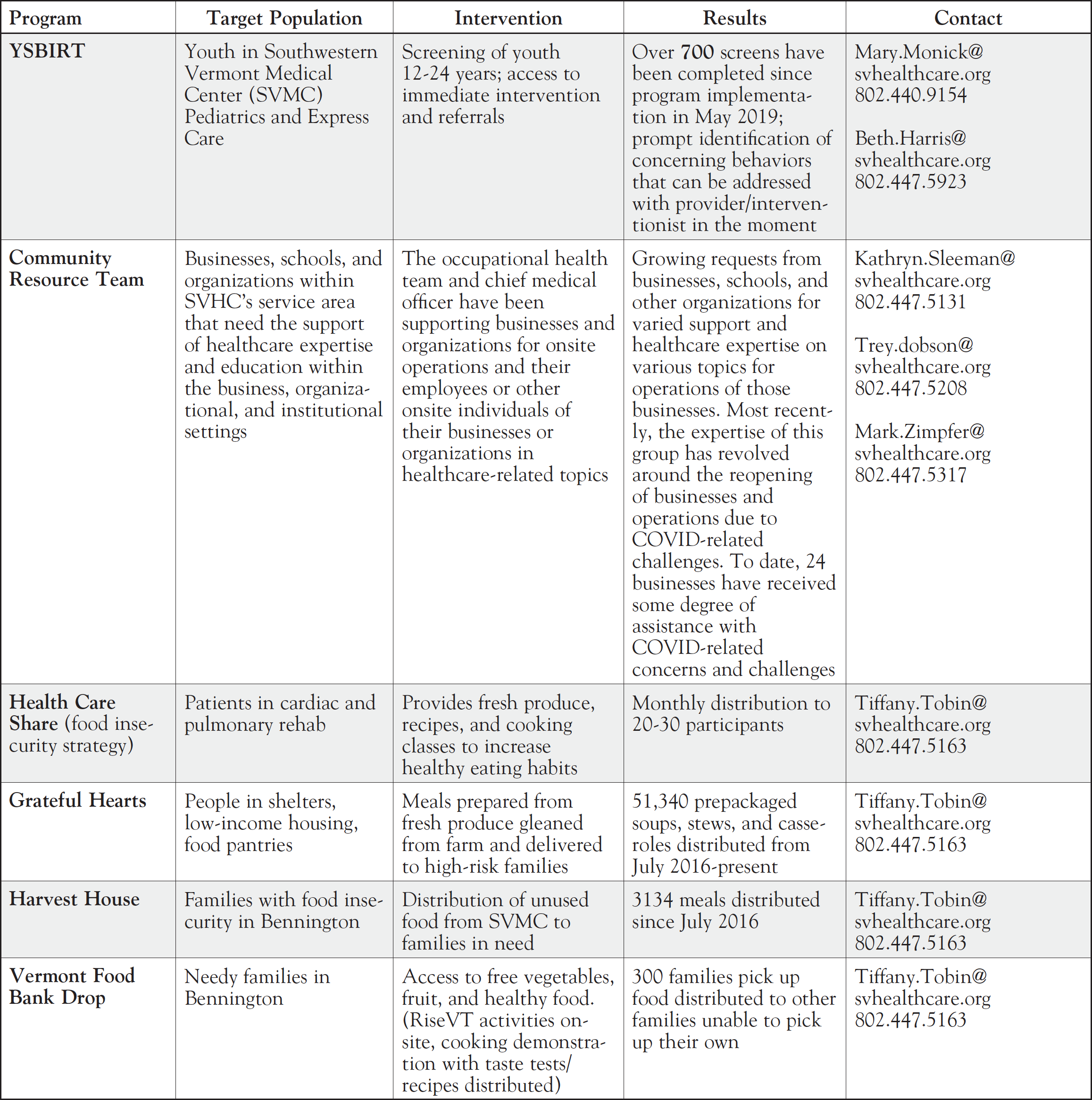

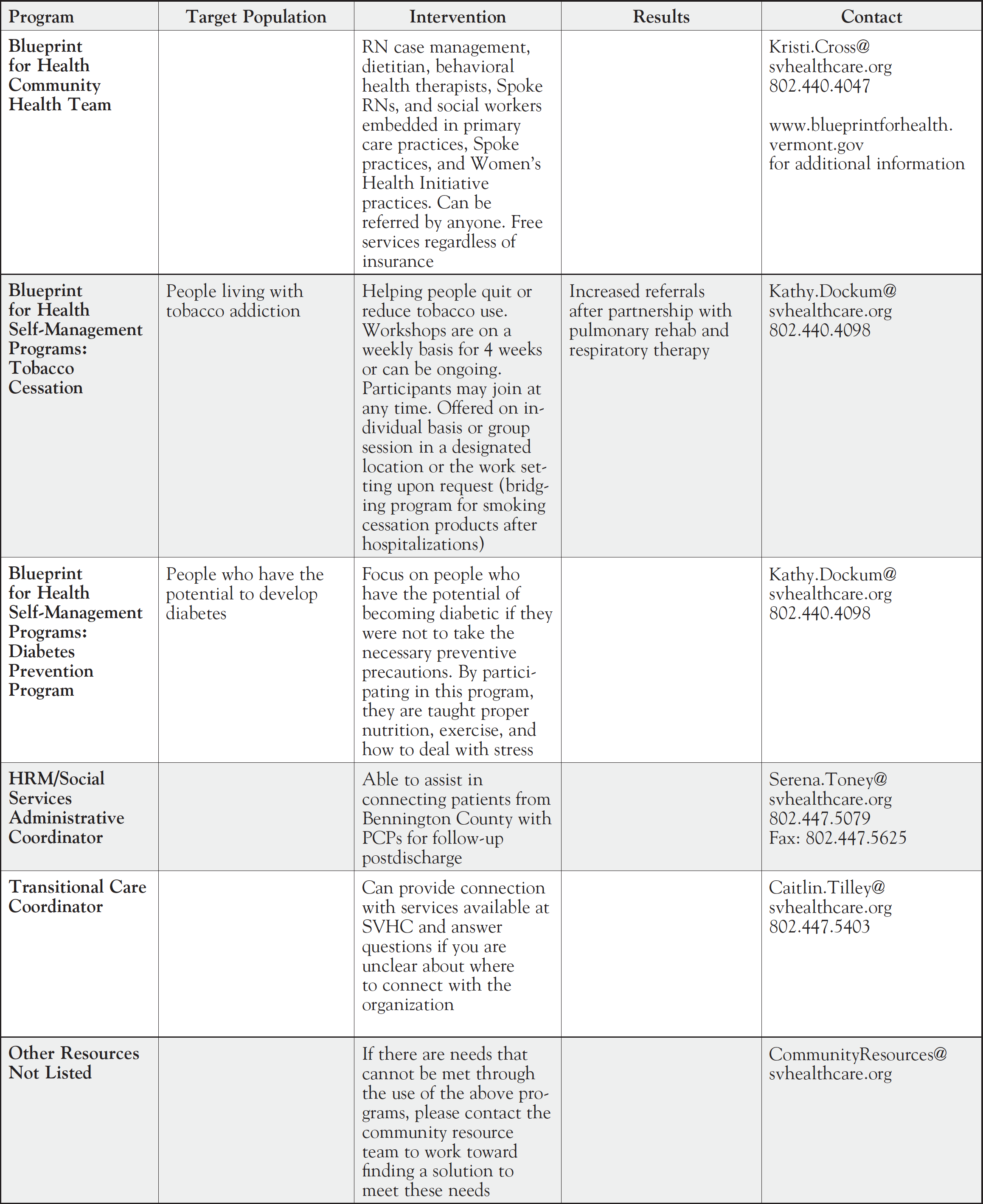

Appendix II: Population Health Programs Available to the Bennington Community

Billie Lynn Allard, MS, RN, FAAN, of Southwestern Vermont Health Care (HVHC)