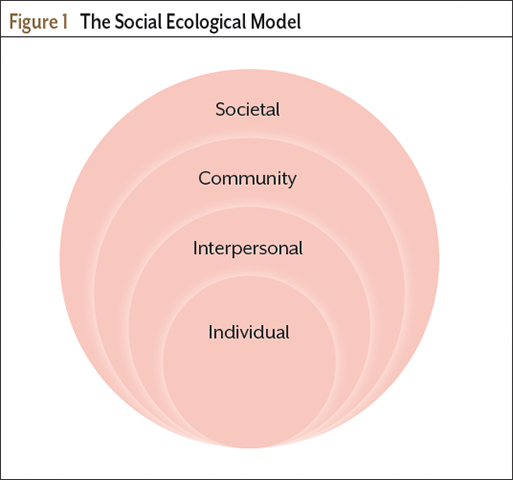

Background: To improve health disparities and breast cancer outcomes for African American (AFAM) women, action is needed at multiple levels of engagement. Breast cancer survivor advocates who volunteer in the community work in individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels to educate, raise awareness, and improve care for themselves and others. The Social Ecological Model (SEM) can help to organize levels of activity and describe how individual, social, and environmental factors can inhibit or enhance advocacy activities in breast cancer survivors.

Methods: Ten AFAM breast cancer survivors in Metro Detroit who had varying lengths of advocacy participation and were in different phases of survivorship were recruited. Open-ended interviews using an innovative participatory action qualitative research method of photovoice sought to understand the types of activities that breast cancer advocates engaged in and the areas where they participated.

Results: The SEM was extremely helpful in categorizing advocacy experiences and organizing different levels of advocacy participation. Advocacy activities often overlapped between levels, and several major themes ran through activities, such as mentions of the AFAM culture, the patient voice, and story sharing. This study shed some light on the interplay between different levels and how breast cancer advocates find the level they are most comfortable with. This study also found that a collective effort is needed and that activities with researchers and healthcare professionals require multiple levels of interaction.

Conclusions: Although many beneficial outcomes have resulted from breast cancer survivor advocates, there is lack of concentration on the characteristics and personalities of the advocates themselves and the types of advocacy activities they engage in. With the increasing willingness of the health system to encourage, embrace, and utilize the knowledge of survivor advocates, it is important for nurses to better understand participation and engagement more fully.

According to the American Cancer Society (2022), an estimated 297,790 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in 2023, and an estimated 43,700 women will die of the disease.1 The rate of being diagnosed with breast cancer and dying of it varies by ethnic/racial group; AFAM women have a 40% higher rate of death than White women.1 Gaining a greater understanding of the multiple processes involved in creating disparities in breast cancer is essential for improved care and outcomes. One potential means to improving these disparities is through survivor advocacy. Breast cancer survivor advocates are individuals who have navigated the complex healthcare systems for their own diagnosis and treatment and used this knowledge to advocate for others.2-7 AFAM breast cancer survivor advocates have a unique understanding of the cultural issues that can hinder the effectiveness of interventions and healthcare practices for AFAM women.4 In addition, the overall experience of being an AFAM in our current healthcare system, including issues related to racism, discrimination, and challenges with patient–provider communication, can provide useful information regarding current barriers that exist during breast cancer care.4,8-11

The motivation to use these experiences, and the collective cultural responsibility to help others in similar circumstances, provides the catalyst for advocates to seek out opportunities to improve breast cancer awareness, treatment, and research.4,12 Breast cancer survivor advocates work on a wide range of activities to improve breast cancer outcomes, including self-advocacy, peer navigation, fundraising, community outreach, research, and public policy. Several studies have examined advocacy within a social ecological theoretical context to determine how and where advocates engage in advocacy.3,7,13,14 The Social Ecological Model (SEM) is a multilevel conceptual framework that helps in the understanding of behaviors and how individuals are impacted by the larger social systems that they are interconnected with.15 Advocacy can be represented within these levels, and the SEM (Figure 1) can describe how individual and environmental factors can inhibit or enhance advocacy activities in breast cancer survivors. This framework was used as a guide in this study to understand the multiple levels where AFAM breast cancer advocates work to improve care. Breast cancer survivors engage in advocacy activities for different reasons and in a variety of ways. The purpose of this study was to organize and describe these activities to gain a deeper understanding of their characteristics and objectives.

Methods

This was a qualitative study that included open-ended interviews using photovoice, an innovative community-based participatory action research method that engages research participants to take photographs of their experiences.16 Participants discussed, analyzed, and displayed photos of their advocacy experiences during the interview to help generate conversation about advocacy involvement. Each interview began with the participant being asked about their experience in advocacy. The interview was guided to understand how their activities fit into the SEM. Additional questions and probes were used to help survivors elaborate more on their experiences. Guided by the SEM (Figure 1), an advocacy questionnaire was developed to assess advocacy participation at different levels (ie, individual, interpersonal, community, societal). Questions were constructed to gain a better understanding of personal, peer, community, research, and legislative advocacy efforts. The intention was to keep the questions open-ended and allow the participants to elaborate on their experience of how they got involved, their first experience with advocacy, and to describe their current, past, and ongoing advocacy pursuits.

Sample and Recruitment

This study targeted AFAM breast cancer survivor advocates who were members of Sisters Network Greater Metropolitan Detroit, a community outreach–based AFAM breast cancer survivorship organization. A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit and enroll 10 participants. After members were recruited, they were asked to collaborate and recruit other eligible breast cancer advocates from the community. Participants were eligible for inclusion as follows: self-identifying as Black/AFAM, completed primary therapy for breast cancer, were older than 18 years, had the ability to read and write in English, and provided informed consent. Individuals were informed that participation was always voluntary, and that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Procedures

Participants who agreed to participate in the study received an information sheet and an introductory 45-minute training session that included general safety issues as well as technical aspects of taking pictures. Consent was obtained for participation in the study and for the sharing of photos. After the initial training session, participants decided on the time needed to take pictures or gather existing photos that they wanted to share. Participants were encouraged to gather photos of their attendance in breast cancer walks, outreach events, and self-advocacy during treatment. They also included pictures of brochures, certificates, clothing items, or other personal mementos.

Data Analysis

Participants were offered the choice of an in-person interview or a virtual interview conducted via Zoom, and all participants chose the virtual option. Permission to record the interview was obtained, and a voice recording software (otter.ai) was then used to facilitate the transcription of the interviews. The researcher read the transcripts while following along with the taped voice recording to check the accuracy of the transcription and edit for clarity. Field notes were taken during this phase to make note of any ideas or thoughts that came up during the process. Transcripts from the interviews were uploaded into the Dedoose (version 9.0.62) software platform17 for data analysis and management. After the text was read several times in its entirety, and the researcher felt familiar with the narrative and its meanings, the codebook was developed and refined. Data were coded manually and through the Dedoose software program.

Significant statements that evolved from repeated key words, major ideas, or concepts that characterized the experience of advocacy were tagged and then color-coded through the software. Following the identification of codes, potential themes were developed. Themes were based on dominant overarching meanings that were identified across the data and how well individual codes fit into these themes. Content was then further refined, and using quotes from the narrative data, themes were finalized and validated.

Interrater Reliability

To establish that data collected in this study correctly represented the variables measured, interrater reliability was calculated. Cohen’s kappa was calculated for coding consistency between researchers. Cohen’s kappa scores range from 0 to 1, with scores at a level of 0.81 to 1.0 indicating very good agreement.18 In this study the Cohen’s kappa was 0.88.17 To ensure consistency within the code system, several of the excerpts were coded together, and coding agreement along with the lack of coding agreement were discussed in depth. Both coders were ultimately able to establish consistency and conclude that the code applications were proficient.

Results

Individuals in this study participated in local advocacy organizations, with the majority identifying as members of Sisters Network Greater Metro Detroit. Twenty percent of participants were also involved with Karmanos Cancer Institute Healthlink Cancer Action Councils, and several participants also mentioned that they were active with Gilda’s Club Metro Detroit, a community-based support organization. Other local and national cancer organizations were mentioned, and many participants stated that they advocated in areas outside of breast cancer before and after their diagnosis. Study findings were analyzed using the SEM framework and grouped according to level (ie, individual, interpersonal, community, societal). Advocacy activities often overlapped between levels, and several major themes ran through activities.

Study findings were analyzed using the SEM framework and grouped according to level. Advocacy activities often overlapped between levels, and several major themes ran through activities.

Demographic Data

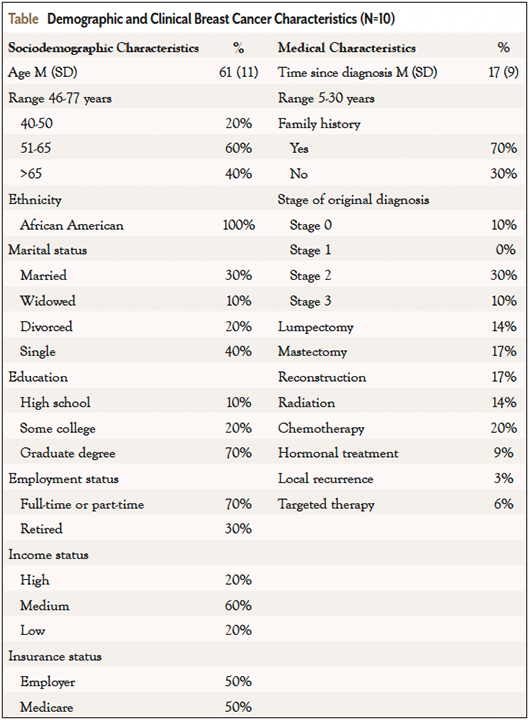

The current age of the study participants was between 46 and 77 years, with a mean age of 61 (SD=11). The length of advocacy participation ranged from 5 to 30 years, with an average time of advocacy of 17 years (SD=9.1). Some breast cancer advocates stated that they took breaks during the advocacy process to focus on other life events but eventually returned to advocacy when time permitted. Other advocates stated that they have never stopped because “there is still more work to be done.” All participants self-identified as Black/AFAM and confirmed a diagnosis of breast cancer. Seventy percent of participants had a graduate degree or higher and worked either part-time, full-time, or described themselves as retired. All participants were fully insured either by employer-based insurance or Medicare, and many participants had a family history of breast cancer. Demographics and clinical breast cancer characteristics are shown in the Table.

Self-Advocacy

Self-advocacy was defined as speaking up for oneself, questioning the medical team, or requesting a second opinion. Many breast cancer survivor advocates stated that they needed to assert themselves to get their questions answered and express their personal preferences during clinical encounters.

Participants advocated with healthcare systems for better insurance coverage of treatment and felt that this was essential to getting good care. Younger participants felt the need to fight for cancer screening at a younger age and emphasized the importance of knowing and being proactive about one’s own body, with the understanding that we are our own best advocates. Self-advocacy involved seeking out others who had breast cancer for advice, partnering with clinicians to discuss options, changing treatments based on current information, and engaging in personal research as needed. Advocates often began by advocating for themselves before advocating for others (Figure 2). One advocate mentioned, “If you’re not your own advocate, no one’s gonna do it for you.”

In an effort to feel connected with their healthcare team and get the care and answers they wanted, participants stated a need for a clinician who listened to them and made them feel comfortable enough to ask questions. One participant stated, “My oncologist and I had a screaming match! (laughs). But we worked it out, and it turned out to be fabulous.” Not all breast cancer advocates participated in self-advocacy. Some who were diagnosed decades ago stated that they did not initially advocate for themselves during treatment. One advocate explained, “I didn’t ask for a second opinion. I had no clue! No insurance, all I had was prayer. I never questioned…” Another participant stated:

Some people don’t question, you know…, they go into the doctor, and they just take them at face value and don’t really explain what’s going on to them or express what their preferences are. So, I think there’s a lack of self-assurance to relate to medical care team as a, a team member rather than a...I don’t want to say boss, but authority figure.

Both participants mentioned that after becoming involved in advocacy, they have become stronger self-advocates, view things differently now, and have learned to speak up for themselves.

Interpersonal Advocacy

Interpersonal advocacy was the strongest level of advocacy for the participants in this study. Participants mentioned providing support and navigation, as well as sharing their personal story, to help encourage others during their cancer journey. Navigation included offering resources to another person, offering to help with tangible needs, or directing them to support groups, financial resources, and other breast cancer organizations. Participants explained that they offered this type of advocacy wherever they were. For example, whether it was a baby shower, grocery store, or exercise class, they offered their personal story, advice, or support to one another:

...She came to me afterward and said, “Well, you know, my niece is going through this.” And so yeah, we chatted about that…I, I’ve recruited… I don’t know, 5 or 6 people just from...my fitness classes. Really. I see lots of people.

One participant described how she frequently shared her story with others:

So, what I can give as far as advice on where to go, and who to talk to or…I give them again, I give them my story. I don’t give them the complete story, but I give them my story.

Another participant stated that although she shared her story to help others, she was also able to benefit from it.

Just as much as I’m sharing my story, to advocate and to bring about change, it’s also therapeutic for me to share my story, to process what I’ve gone through, and to be very grateful that I’ve made it through it.

Community Advocacy

Community advocacy involves participation in different advocacy organizations, breast cancer events, and various fundraising opportunities. Community breast cancer survivor advocates looked to create change and influence outcomes by spreading awareness on social media or by sharing personal stories at public community gatherings or conferences. Community events that were held to educate both the community and advocates included informal talks, webinars, seminars, and presentations to raise awareness, as well as to educate about new treatments, research, and policy initiatives. Advocates enjoyed learning at these events, and they also invited friends, coworkers, family, and members of the community to attend. Fundraising was a common activity done at the community level and included large community walks, small personal contributions, or supporting another survivor in their advocacy activities. Large events often served to educate, fundraise, support, and celebrate.

We get out there, and we demonstrate that we…, we let people see…that we have breast cancer, and we’re still alive…that breast cancer is not a death sentence.

One community event that many advocates took part in was the Sisters Network Gift for Life Block Walk. Several participants interviewed discussed this event and their involvement in the community by walking through underserved neighborhoods in Detroit, knocking on doors, educating residents on breast cancer, and offering support (Figure 3). This was a way not only to connect with other survivors but also to get information out and engage with the community about breast cancer.

Well, what we do…we go get people, gather at a facility, and we walk and go door to door and ask…get the information out about our breast cancer organization. And anyone in the family had breast cancer, they could come back and have lunch with us and stuff like that. And we tell them a little…we pass out literature and tell them about our organization, and that’s how we try and get the word out in the neighborhood, and in the community.

Societal Level Advocacy

Societal level advocacy moves beyond helping others at the local level and includes national efforts to improve the treatment, care, and prevention of breast cancer. Advocacy at this level was mainly composed of discussions about research and legislative advocacy. Participants were asked if they ever participated in clinical trials or endorsed them. They were also asked if they had ever sent a letter, an email, or spoken to a public policymaker to express their opinion about changes they would like to see happen in cancer care or cancer research funding. Breast cancer survivor advocates discussed hosting and participating in national breast cancer conferences where they learned more about research and policy and how they can be more involved in the AFAM community (Figure 4).

So once periodically, the National Chapter of Sisters Network travels around the country. They asked different chapters to sponsor this conference. So…this was the year that we sponsored…it downtown. We had speakers come in to discuss different aspects of breast health and the new research coming up and treatment and, and it was a fabulous event. It was very well attended.

Research Advocacy

Most participants stated that they advocated in support of research and clinical trials. Participants described positive feelings toward research in that it gave them options outside traditional therapies. Breast cancer survivor advocates participated in peer review and events that had speakers on clinical trials and research, and many participants emphasized the importance of AFAM participation in clinical trials. Advocates discussed directly participating in a clinical trial, sharing their story about participation, and encouraging or recruiting others to join a trial. One participant discussed her participation on a community panel about clinical trials in the AFAM community:

I was a moderator of one of the community Grand Rounds at [name of hospital]. And that was the topic, clinical trials, and I am definitely an advocate because when I went through my treatment, I participated in a clinical trial.

Breast cancer survivor advocates participated in peer review and events that had speakers on clinical trials and research, and many participants emphasized the importance of AFAM participation in clinical trials.

Participants discussed mistrust in research and mentioned the historical exploitation and misuse of research in the AFAM community, but they felt that was in the past and that many could benefit from new treatments. One participant stated that to get over past history, it is now necessary to go out and increase education. Some participants mentioned changed attitudes toward clinical trials, and after watching others’ success with trials, they have changed their thoughts in a more positive direction. There was also a feeling that there was a lack of awareness about clinical trials, and that trials were designed so that AFAM women didn’t quality or were not recruited enough.

The different hospitals…don’t ask for…black women to join trials. They have different trials, but we don’t…get them…We don’t never get in, and I wonder why because I sign up for one at [local hospital] and they never call me in for one, and I wanted to know why trials is not for black women?

Legislative Advocacy

Breast cancer survivor advocates at the legislative level worked with different organizations, either directly advocating in person or indirectly by signing petitions, writing letters, or talking to legislators and staff members on the phone. Areas of concern at this level included affordable treatment, insurance coverage for oral chemotherapy drugs, screening, and reducing medication costs. Advocates wanted not only to influence legislators but also to hold them accountable and emphasized how voting was an important part of advocacy. Advocates engaged at the state level by visiting the state’s capital or by traveling to Washington, DC, and meeting with legislators on Capitol Hill.

Our group, we went to Lansing, and we lobbied in Lansing…and we wrote letters to our different congressmen.

Discussion

Survivors who have been breast cancer advocates for decades as well as survivors who are new to breast cancer advocacy explored different areas and eventually found the level of advocacy they were most comfortable with. Many participants expressed the importance of advocating for themselves to receive the treatment they wanted. Self-advocacy is an important aspect of effective communication with healthcare providers and is necessary for active decision-making and patient-centered care.19 Other research has shown that learning to be an active partner with one’s healthcare team is essential to optimal breast cancer outcomes.20 While some advocates reported strong self-advocacy at the beginning of treatment, there were other advocates who initially did not self-advocate out of fear or because of lack of knowledge about health- and cancer-related topics. They stated that they did what the doctor told them and did not initially question their treatment plan. Later, after becoming involved in advocacy groups, they learned new information and began to gain confidence to speak up and engage with their healthcare providers in a more active way. Skills learned from advocacy can help cancer survivors in the future as they navigate the healthcare system for other health concerns. Self-advocacy development is an important tool as cancer survivors continue through survivorship and surveillance.

Advocacy, at the interpersonal level, involved giving and receiving support. Research has supported that having a group of cancer survivors who are willing to talk with the newly diagnosed and share their experiences can help provide needed support during the early diagnosis phase of cancer.21,22 This information builds on other studies to further strengthen the encouragement of AFAM survivors in outreach and advocacy organizations for personal as well as collective benefit.

At the community level, advocates participated in a wide variety of outreach events, conferences, and breast cancer walks. They felt it was important to have a visual presence at these events to show others in the community that cancer is survivable and that AFAM support organizations are available. To reach members of the community with breast health information, research has shown that it is important to first establish trust and rapport.23-26 The collaboration of survivor advocates with researchers and healthcare systems is a good way to offer social and supportive resources in a nonthreatening manner among peers and ensure that the information is delivered in a culturally appropriate manner.

Societal level advocacy activities revolved mainly around research and clinical trials. Many of the advocates in this study have personally participated in clinical trials or endorsed the benefits of trial participation. Previous research has shown that AFAM women have difficulty getting the information they need about clinical trials, have fewer conversations about trials with their providers, and lack trust due to historical injustices.27,28 More research is needed on AFAM advocates who have participated in clinical trials, as they could provide information on how to increase minority engagement. Many of the participants who engaged in legislative advocacy stated they understood the importance of health policy, but current ongoing participation was lacking. More interventions are needed on the unmet needs of AFAM cancer survivors who move into legislative advocacy to identify the barriers that keep them from continued involvement.

Societal level advocacy activities revolved mainly around research and clinical trials. Many of the advocates in this study have personally participated in clinical trials or endorsed the benefits of trial participation.

Conclusions

Using a research orientation that places emphasis on patient knowledge and experience may be one way of improving outcomes in breast cancer care and reducing health disparities. Breast cancer survivor advocates have the potential to influence the health behaviors in their communities and provide insight into which personal characteristics enabled them to make informed treatment decisions. Gaining information into how survivor advocates were able to engage effectively and communicate with their healthcare providers and find cultural support networks may help resolve ongoing disparities in care. Advocacy has the potential to make an impact at the individual, interpersonal, and community level and helps to bring a sense of purpose to treatment and research.29 Having more knowledge about the experiences and activities of survivor advocates allows clinicians the understanding needed to work effectively with this population. Based on the positive feedback that advocates related during this study, more interventions are needed to include this population in breast cancer care and in the struggle to end disparities.

References

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2022-2024. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/2022-2024-breast-cancer-fact-figures-acs.pdf

- Ashing KT, Miller AM, Mitchell E, et al. Nurturing advocacy inclusion to bring health equity in breast cancer among African American women. Breast Cancer Manag. 2014;3:487-495.

- Clark EJ, Stovall EL. Advocacy: the cornerstone of cancer survivorship. Cancer Pract. 1996;4:239-244.

- Lythcott N, Green BL, Kramer Brown Z. The perspective of African-American breast cancer survivor-advocates. Cancer. 2003;97(suppl):324-328.

- Mollica MA, Nemeth LS, Newman SD, et al. Peer navigation in African American breast cancer survivors. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:131-144.

- Smith A, Vidal GA, Pritchard E, et al. Sistas taking a stand for breast cancer research (STAR) study: a community-based participatory genetic research study to enhance participation and breast cancer equity among African American women in Memphis, TN. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15;2899.

- Zebrack B. An advocate’s perspective on cancer survivorship. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001;17;284-287.

- Krieger N, Jahn JL, Waterman PD. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992-2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28;49-59.

- Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, et al. An analysis of race-related attitudes and beliefs in black cancer patients: implications for health care disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27;1503-1520.

- Sutton AL, He J, Edmonds MC, Sheppard VB. Medical mistrust in black breast cancer patients: acknowledging the roles of the trustor and the trustee. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34: 600-607.

- White-Means SI, Osmani AR. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication with breast cancer patients: evidence from 2011 MEPS and experiences with cancer supplement. Inquiry. 2017;54:46958017727104.

- Flannery IM, Yoo GJ, Levine EG. Keeping us all whole: acknowledging the agency of African American breast cancer survivors and their systems of social support. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27;2625-2632.

- Hoffman B, Stovall E. Survivorship perspectives and advocacy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;24:5154-5159.

- Molina Y, Mckell MS, Mendoza N, et al. Health volunteerism and improved cancer health for Latina and African American women and their social networks: potential mechanisms. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33:59-66.

- Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:364-372.

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369-387.

- Dedoose. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.Dedoose.com

- Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1997;33:363-374.

- Thomas TH, Donovan HS, Rosenzweig MQ, et al. A conceptual framework of self-advocacy in women with cancer. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2021;44;E1-E13.

- Anderson JN, Graff JC, Krukowski RA, et al. “Nobody Will Tell You. You’ve got to ask!”: an examination of patient-provider communication needs and preferences among black and white women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Commun. 2021;36;1331-1342.

- Ashing-Giwa K, Tapp C, Rosales M, et al. Peer-based models of supportive care: the impact of peer support groups in African American breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:585-591.

- Corvin J, Coreil J, Nupp R, Dyer K. Ethnic differences in cultural models of breast cancer support groups. International Journal of Self-Help and Self-Care. 2013;7(2):193-215.

- Bellhouse S, McWilliams L, Firth J, et al. Are community-based health worker interventions an effective approach for early diagnosis of cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2018;27:1089-1099.

- Knobf MT, Erdos D. “Being connected” The experience of African American women with breast cancer: a community-based participatory research project: Part I. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2018;36:406-417.

- Shelton RC, Dunston SK, Leoce N, et al. Advancing understanding of the characteristics and capacity of African American women who serve as lay health advisors in community-based settings. Health Educ Behav. 2017; 44:153-164.

- Smith MA, Conway-Phillips R, Francois-Blue T. Sisters saving lives: instituting a protocol to address breast cancer disparities. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:427-432.

- Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, et al. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans’ participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:13-32.

- Eggly S, Barton E, Winckles A, et al. A disparity of words: racial differences in oncologist-patient communication about clinical trials. Health Expect. 2015;18:1316-1326.

- Molina Y, Scherman A, Constant TH, et al. Medical advocacy among African-American women diagnosed with breast cancer: from recipient to resource. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3077-3084.