Joanna Abi Chebl1,3; Lidia A. Vognar1,3,4; Jayme Dandeneau2; Mercy Jimenez3; Le Hanh Dungo Do1,3; Ponnandai S. Somasundar2,3

1Department of Geriatric Medicine, Roger Williams Medical Center, Providence, RI

2Department of Surgical Oncology, Roger Williams Medical Center, Providence, RI

3Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA

4Department of Medicine, Brown University, Providence, RI

Background: Of the 1.9 million new cancer diagnoses made in 2022, 55.8% were made in adults aged 65 years and older. The care of these patients differs from that of the general adult cancer population mainly because these patients are vulnerable to geriatric syndromes such as dementia, frailty, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy.

Objectives: The Geriatric Surgery Verification (GSV) Program is designed to improve surgical care and outcomes for older adults, aiming to provide early intervention and prevention strategies to maximize therapeutic response using multidisciplinary team approaches.

Population and setting: We evaluated the implementation of the GSV Program in a small community hospital, Roger Williams Medical Center (RWMC), based in Rhode Island. RWMC is a teaching community hospital that has an established geriatric surgical oncology department.

Methods: As part of GSV implementation, the Geriatric Surgery Quality Committee was established, which consists of a geriatric surgery director, coordinator, nurse navigator, registered nurses, case manager, surgical specialty representatives, and a geriatrician. All patients referred to the surgery oncology clinic were evaluated for the GSV Program starting in April 2022. Of those, 50 patients met age criteria and were assessed utilizing the Age-Friendly Health Systems 4Ms framework for what matters, mobility, medication, and mentation.

Results: This yielded 12 referrals for specific interventions dependent on deficits identified upon evaluation, including 6 geriatric medicine referrals, 1 social worker referral, and 5 nutrition referrals. Outcome measures collected include patient satisfaction, delirium diagnosis, palliative care, and hospice utilization.

Conclusion: The GSV Program has demonstrated impact on patient satisfaction, with patients and caregivers noting additional support through transitions of care, increased inpatient geriatric medicine consults, earlier identification of patients at high risk for developing delirium, and increased utilization of palliative and hospice services.

There are currently more than 56 million adults aged 65 years and older in the United States. This geriatric population is the fastest growing, with expectations to rise from 16.8% to 22% in the upcoming year.1 Among this population, cancer remains a common diagnosis. Of the 1.9 million new cancer diagnoses made in 2022, 55% were in the geriatric population, with the median age at time of diagnosis being 66 years.2 Cancer care has undergone incredible development over the past 3 decades, with improved treatment modalities, increased access to care and treatment across all age groups, and decreased overall cancer mortality of 32%.2 Currently, the percentage of older adults actively undergoing cancer surgery or treatment differs based on the cancer site. Historically, cancer care options have not been delineated by age group but more by cancer type and stage, leading to the application of standardized cancer care across all age groups, including the geriatric population.3 In a retrospective review of 81 patients with treatable head and neck cancer, 62% of those older than 65 years received radiation therapy along with 2 chemotherapy agents.4,5 In another retrospective review, conducted at multiple institutions, therapeutic interventions were examined for 131 older adult patients with ovarian cancer.4,6 Of those between the ages of 70 and 79 years, 89% underwent debulking surgery, and 87% received platinum-based combination chemotherapy.4,6 However, applying the same model of care to all cancer patients regardless of age can have unfavorable outcomes. Studies have shown that geriatric patients have increased rates of cancer care complications, including depression and anxiety (18%), falls and fractures (20%-40%), difficult pain control (40%-55% during and after cancer treatment), fatigue (>70%), cognitive impairment known as chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (70%), and malnutrition (66%).7,8

Historically, cancer care options have not been delineated by age group but more by cancer type and stage, leading to the application of standardized cancer care across all age groups, including the geriatric population.

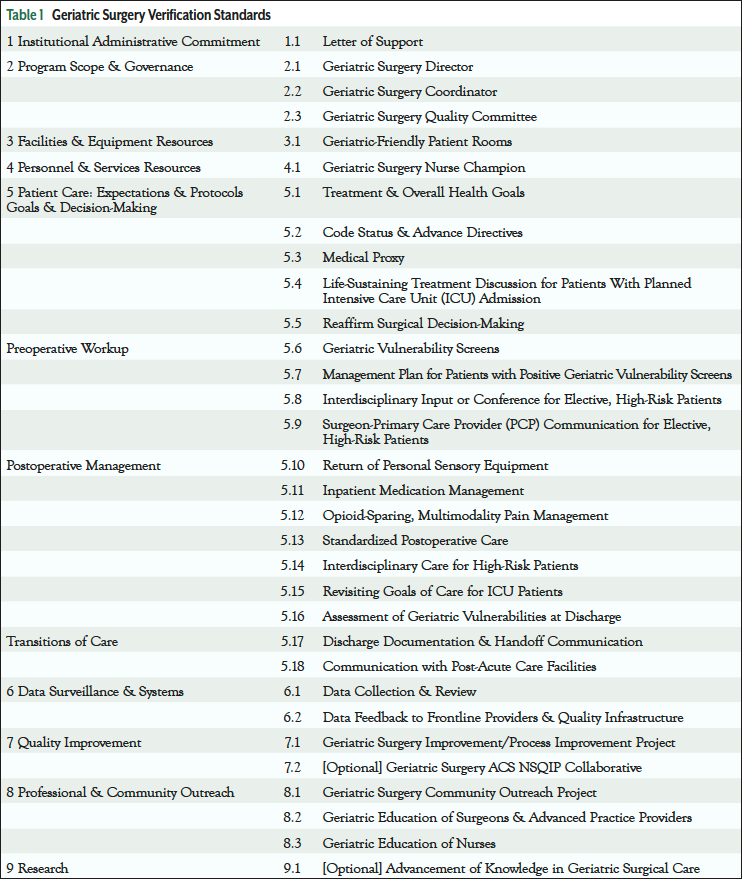

To improve cancer care management and outcomes in the geriatric population, the Geriatric Surgery Verification (GSV) Program was developed by the American College of Surgeons in 2019 with support from The John A. Hartford Foundation.9 The program encompasses 32 evidence-based standards of geriatric surgical care aimed at improving perioperative and postoperative outcomes for older adults, with a strong utilization of the Age-Friendly Health Systems 4Ms framework of what matters, mobility, medication, and mentation.9,10

This program is now being implemented in 32 hospitals in the United States.11 Hospitals involved include academic teaching hospitals, community for profit and not for profit hospitals, rural hospitals, VA hospitals, and cancer treatment centers.11 Hospitals can apply for a GSV Verification Level 1 or Level 2, for which all required standards must be implemented and a site visit conducted, or they can apply for the GSV Commitment Level, where no site visit is performed, but the hospital is expected to be actively preparing for verification for up to 24 months.11 The hospitals currently implementing GSV have either been verified or are part of the Commitment Level, and the number of hospitals in the process of seeking verification for Level 1 or Level 2 continues to rise. The aim of this paper is to share a surgical oncology nurse navigator’s perspective from the ground up on the implementation of the GSV Program in a small community teaching hospital with limited resources.

GSV Implementation Process

We evaluated the implementation of the GSV Program in a small teaching community hospital with limited resources. Roger Williams Medical Center (RWMC) is the smallest teaching community hospital to implement the GSV Program, both locally and nationally.11 RWMC has an established geriatric surgical oncology department and an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2-year surgical oncology fellowship. The geriatric surgical oncology department physician team is staffed by 4 surgical oncologists, 2 physician assistants, 1 nurse navigator, 2 nurse champions, 6 surgical floor nurses, and 2 surgical oncology fellows. This department has a high level of GSV implementation commitment per GSV standards.

As part of this certification process, the Geriatric Surgery Quality Committee (GSQC) was established, consisting of a geriatric surgery director, coordinator, nurse navigator, registered nurses, case manager, surgical specialty representatives, and a geriatrician. All patients aged 65 years and older who presented to the RWCC with newly diagnosed solid cancers were evaluated for the GSV Program. The purpose of implementing the program and gathering the data produced is to improve cancer care management and associated patient care outcomes.

GSV implementation criteria encompass institutional commitment, facility and equipment resources, dedicated personnel, and patient care expectations including decision-making, preoperative workup, postoperative management, transitions of care, data surveillance, quality improvement, and professional community outreach (Table 1).10 The GSV nurse navigator represents a central entity linking GSV Program standards and GSV Program development. The nurse navigator role includes identification of appropriate patients, preoperative assessment, optimization of postoperative care, and provision of patient education and support throughout the entire process. The GSV nurse navigator is also responsible for educating the geriatric surgical oncology team, coordinating consultative efforts with geriatric medicine, and providing current reports on systemwide efforts to hospital administration.

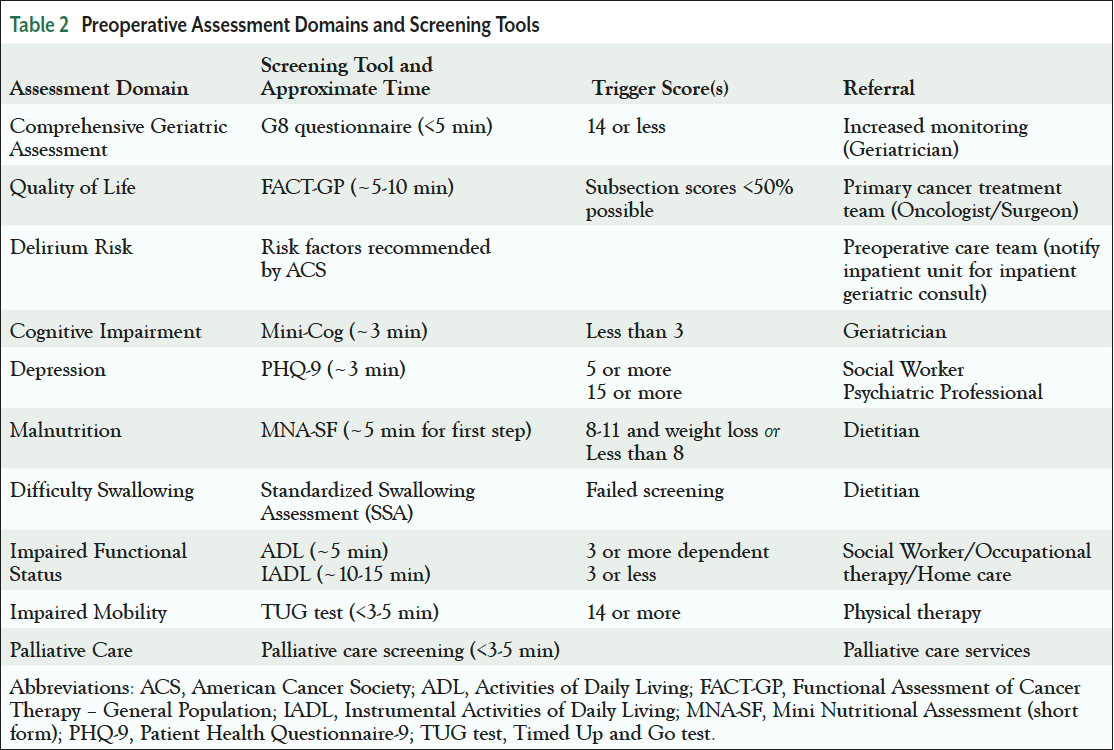

At RWMC, the nurse navigator is stationed within the surgery oncology department and is the lead of the GSQC, which is designed to uphold the GSV criteria listed above. The GSV nurse navigator identifies all patients aged 65 years and older with newly diagnosed solid cancers. The GSV nurse navigator is then responsible for triaging these identified patients and completing the preoperative assessments in clinic, at the bedside, or by phone when applicable (Table 2). Patient assessments are in the domains of cognitive, functional, and nutritional status. The GSV nurse navigator follows the patient through the surgical intervention, hospital admission, and for 3 months after discharge.

For GSV implementation to be successful, the GSV nurse navigator also needs to continually monitor for GSV buy-in from the GSV committee participants. Institutional commitment and resource support need to be established prior to GSV implementation and then fostered throughout the process with frequent updates and progress reports. The GSV nurse navigator, as the lead of the GSV committee, has an integral role in this as well, serving as a bridge between “in the field” work and hospital administration goals.

Another key component of successful implementation is the role of the geriatrician. RWMC has an ACGME-accredited geriatric fellowship, and geriatric fellows are required to participate in the GSV Program. High-risk patients identified by the nurse navigator are referred to geriatric medicine for preoperative evaluation. Patients are assessed utilizing the Age-Friendly Health Systems 4Ms framework.9 The geriatrician assesses cognitive status by screening for depression, dementia, and delirium, then evaluates functional and nutritional status, along with a thorough review of patient medication and identification of possible polypharmacy. Provider then identifies what matters most to the patient regarding a treatment plan and goals of care moving forward. The geriatrician then follows the patient throughout their inpatient stay, continuing to monitor the 4Ms very closely.

Process implementation was evaluated utilizing Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology. PDSA cycle 1 represents the first 4-month period of GSV implementation, from April 1, 2022, to July 31, 2022. PDSA cycle 2 represents the next 5-month period of GSV implementation, from August 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022.

GSV Institutional Buy-In

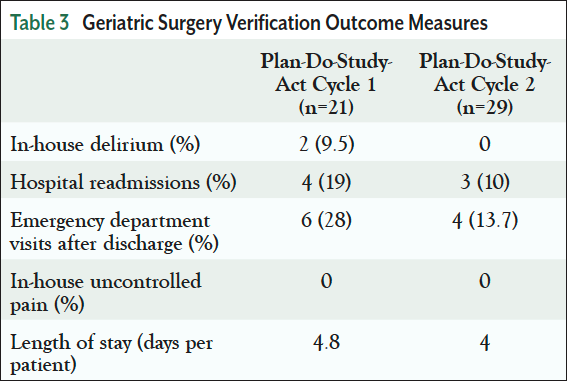

The state of Rhode Island has one of the highest proportions of adults aged 85 and older, ranking it first in New England.12 RWMC patient demographics mirror the above, with the hospital typically serving a much older patient demographic.13 RWMC has a senior-friendly emergency department and is home to the state’s first and only geriatric surgery oncology program.14,15 Despite the administration being supportive of age-friendly initiatives, RWMC is a small community hospital with limited resources. Institutional buy-in is imperative for the GSV Program to be successful, as implementation criteria mandate institutional commitment and allocation of facility and equipment resources.11 At RWMC, buy-in was aided by initial analysis reports that showed a significant reduction in length of geriatric surgery oncology patient stay. Data were collected from the 2 PDSA cycles (Table 3). The first cycle included 21 subjects, and the total length of stay (LOS) was 101 days, averaging 4.8 days per patient. The second PDSA cycle included 29 subjects, with a total LOS of 118 days, averaging 4.0 days per patient. With GSV implementation, LOS per patient decreased by 16.7%.

GSV Outcome Measures

At RWMC, GSV outcome measures collected include patient satisfaction, delirium diagnosis, in-house pain control, hospital readmissions, emergency department visits after discharge, and LOS (Table 3). All patients referred to the surgery oncology clinic between April 2022 and December 2022 were evaluated for the GSV Program. Of those, 50 patients met age criteria, with the mean age being 74 years. This yielded 12 referrals for specific interventions dependent on deficits identified upon evaluation. There were 6 geriatric medicine referrals, 1 social worker referral, and 5 nutrition referrals. All patients in both PDSA cycles had adequate in-house pain control. In the first PDSA cycle, 9.5% of patients experienced in-house delirium; no patients experienced in-house delirium in the second PDSA cycle. In the first PDSA cycle, 19% of patients were readmitted to the hospital; 10% of patients were readmitted in the second PDSA cycle. In the first PDSA cycle, 28% of patients had to revisit the emergency department post hospital discharge; 13.7% of patients in the second PDSA cycle reported visits post discharge. Patient satisfaction was captured by the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire that covers 5 dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.13,16

Patients were evaluated after discharge by the surgical oncology nurse navigator. Follow-ups were scheduled, and outcome measures were collected at 7, 30, 60, 90, and 180 days postoperatively. The timely care provided extensively at regular intervals by the nurse navigator allowed for preemptive identification of risk factors.

Discussion

GSV implementation at RWMC has thus far demonstrated great impact on patient satisfaction, with patients and caregivers noting additional support through transitions of care, increased inpatient geriatric medicine consults, earlier identification of high-risk patients for developing delirium, and increased awareness of palliative and hospice services. Implementation of the GSV Program has allowed the nurse navigator to identify patients who qualified for transitions of care programs, including skilled nursing facilities and home health programs with services, thus facilitating patient care across the continuum. Through collaborative efforts with geriatric medicine, GSV Program implementation has helped increase awareness among the GSV surgical oncology team in utilizing hospice and palliative care services. In addition to specialty referrals, the nurse navigator refers postoperative patients to physical and occupational therapy, nutrition specialists, and geriatricians while also coordinating surgical postoperative follow-up visits. To capture education efforts, the GSV Program has also led to the development of a geriatric surgery oncology curriculum with increased teaching and training of surgical oncology and geriatric fellows. Fellows can attend weekly consult collaborations and joint didactics on geriatric surgery–specific topics. Lastly, the formation of the GSQC allowed for a multidisciplinary team approach to GSV patient care. All members of the GSQC attended quarterly meeting schedules to discuss updates in GSV Program implementation at RWMC, with weekly meetings held when required to discuss patient-specific high-risk cases. All the above have helped build a standardized approach to GSV patient care as well as improve associated outcome measures as noted.

Barriers to GSV Implementation

GSV implementation requires that documentation of patient care preferences at the time of surgical evaluation be captured via goals of care discussions or Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form completion. This presented a barrier at RWMC initially, demonstrating the challenges still faced in other institutions as well in applying the GSV Program and the difficulty in bringing together patient care preference with medical decision-making. To provide better utilization of hospice and palliative care services, efforts are being made to increase familiarity of such models of care among the geriatric surgical oncology team. Another barrier to RWMC GSV implementation was staff retention. Retention of experienced staff is paramount during the process, particularly in the nursing sector, as the nursing profession enters another era of shortage. During PDSA cycle 1, there was staff turnover for nurse navigators, social workers, and registered nurses. During PDSA cycle 2, there was stabilization of GSV team members without additional staff turnover. Because GSV implementation relies heavily on nurse and nurse navigator roles, it is imperative to encourage interventions that will promote staff retention, participation, and recognition. Lastly, the quality-of-life questionnaire was not used in PDSA cycle 1 due to awaited approval from the original authors. We were able to use the questionnaire starting with PDSA cycle 2.

GSV implementation requires that documentation of patient care preferences at the time of surgical evaluation be captured via goals of care discussions or Medical Orders for Life- Sustaining Treatment form completion.

Conclusion

“We are so glad to have you on board with us through every step of the way,” stated one of the geriatric surgical oncology patients to the GSV nurse navigator. We know that the American population is aging, and there are more adults aged 65 and older than ever before.1 Sadly, cancer diagnosis is also increasing, with 57% of the 1.9 million new cancer diagnoses made in 2022 being in the geriatric population.2 Studies support that geriatric patients have increased rates of cancer care complications, and that the “one fits all” approach to treatment is often not applicable. The GSV Program has been studied and presented as a possible solution to this problem. At RWMC, we were able to successfully implement the program with the GSV nurse navigator playing a central role not only in bridging GSV Program standards and implementation efforts with hospital administration but also in identifying appropriate patients, performing preoperative assessment, optimizing postoperative care, coordinating care across the continuum, and providing patient education and support throughout the entire process. Our GSV patients benefited from appropriate inpatient pain control, experienced decreased in-house delirium diagnoses, and improved satisfaction, with special acknowledgment of the nurse navigator support. There were also benefits to our healthcare system with reduced emergency department visits, fewer postoperative hospital readmissions, and reduced LOS of 4 days per patent. In conclusion, implementing the GSV Program at RWMC, a small teaching community hospital with limited resources, has proved to be possible with clear benefit for patient care and our healthcare system.

References

- America’s Health Rankings. Population - Adults Ages 65+ in the United States. www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/senior/measure/pct_65plus/state/ALL.

- American Cancer Society. Risk of Dying from Cancer Continues to Drop at an Accelerated Pace. Published January 12, 2022. www.cancer.org/latest-news/facts-and-figures-2022.html#:~:text=The%20risk%20of%20dying%20from,for%20which%20data%20were%20available

- Cancer.Net. Cancer Care Decisions for Older Adults. Published February 25, 2022. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/adults-65/cancer-care-decisions-older-adults.

- Berger NA, Savvides P, Koroukian SM, et al. Cancer in the elderly. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:147-155.

- Savvides P, Trang TT, Greskovich J, et al. Analysis of elderly (≥ 65 yrs) patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiation therapy for primary treatment of locoregionally advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck: a single center’s experience. Presented at the XVIII International Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (IFOS) World Congress, Rome, Italy. 2005.

- Uyar D, Frasure HE, Markman M, von Gruenigen VE. Treatment patterns by decade of life in elderly women (> or = 70 years of age) with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98:403-408.

- Shahrokni A, Wu AJ, Carter J, Lichtman SM. Long-term toxicity of cancer treatment in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:63-80.

- Tan HJ, Saliba D, Kwan L, et al. Burden of geriatric events among older adults undergoing major cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1231-1238.

- Zhang L, Escobedo M, Russell MM. Age Friendly - New Standards for Age-Friendly Surgical Care. Journal of the Catholic Health Association of the United States. 2022. www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/archive/article/winter-2021/age-friendly---new-standards-for-age-friendly-surgical-care

- Ma M, Zhang L, Rosenthal R, et al. The American College of Surgeons Geriatric Surgery Verification Program and the practicing colorectal surgeon. Semin Colon Rectal Surgery. 2020;31:100779.

- American College of Surgeons. Geriatric Surgery Verification. www.facs.org/quality-programs/accreditation-and-verification/geriatric-surgery-verification

- Rhode Island Office of Healthy Aging. Key Facts. https://oha.ri.gov/who-we-are/key-facts

- Montroni I, Ugolini G, Saur NM, et al. Quality of life in older adults after major cancer surgery: the GOSAFE International Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:969-978.

- CharterCARE. Cancer Center/Bone Marrow Unit. 2022. www.chartercare.org/services/cancer-center

- American Hospital Association. Roger Williams Medical Center - Senior-Friendly Emergency Departments. www.aha.org/case-studies/2016-01-01-roger-williams-medical-center-senior-friendly-emergency-departments

- Devlin N, Parkin D, Janssen B. Methods for Analysing and Reporting EQ-5D Data. Springer; 2020.