Linda Nguyen, BS1; Hunter Park, BS1; Kelsi Batioja, BS1; Natasha Bray, DO1; Benjamin H. Greiner, DO2; Micah Hartwell, PhD1,3

1Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine at Cherokee Nation, Office of Medical Student Research, Tahlequah, OK

2University of Texas Medical Branch, Department of Internal Medicine, Galveston, TX

3Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tulsa, OK

Background: More than 1.6 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year. Despite the different treatment options available for cancer, many individuals refuse treatment for various reasons. However, little is known about the cumulative group of individuals who refuse treatment.

Objective: Our primary objective was to use the 2017-2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to quantify the number of individuals who refuse or delay treatment by cancer type and conduct a demographic analysis of these individuals. Secondarily, we aimed to assess whether individuals who refuse or delay cancer treatment have different levels of pain compared to those who receive treatment.

Population and Setting: Individuals diagnosed with cancer who were respondents to the 2017-2020 BRFSS. Secondary data analysis of 2017-2020 BRFSS.

Methods and Study Design: We performed a cross-sectional study using the 2017-2020 BRFSS to analyze the prevalence of individuals who refuse or delay cancer treatment by type of cancer and sociodemographics using chi-square tests. In addition, we used logistic regression to determine whether individuals who refused treatment were more likely to report cancer-related pain.

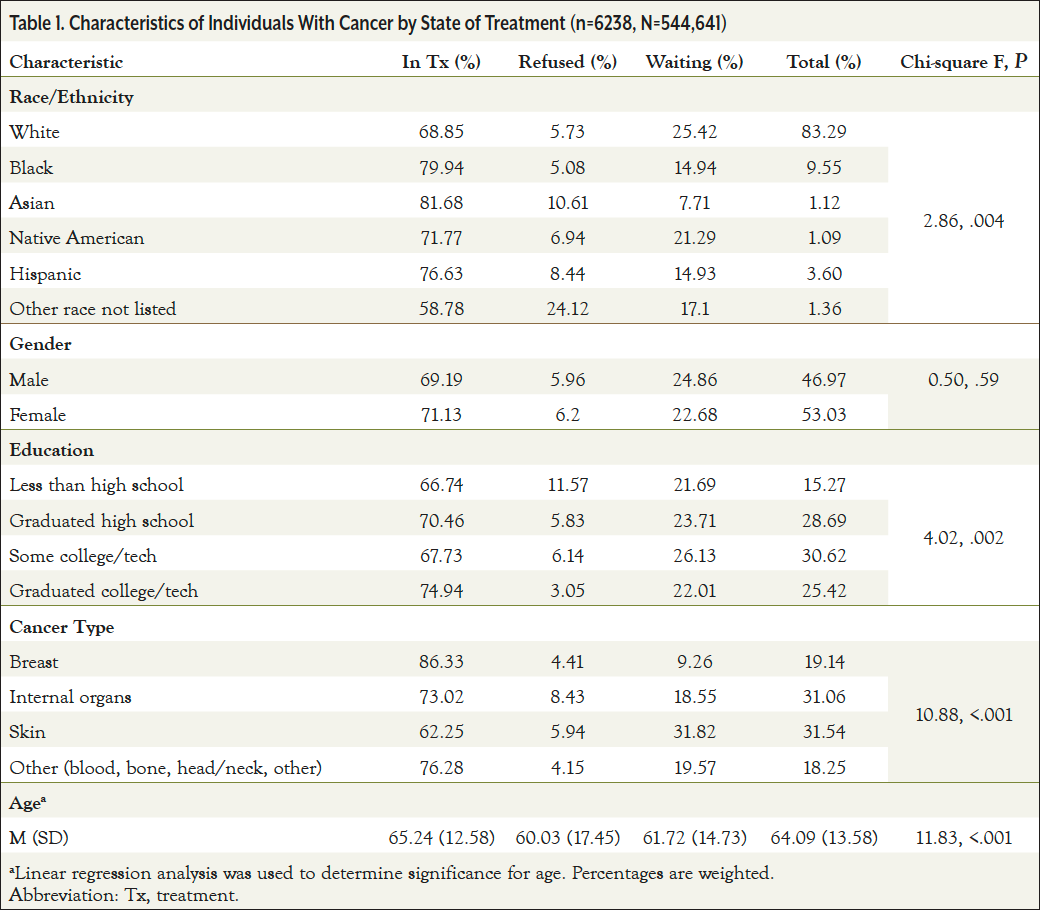

Results: The sample included 6238 individuals of whom 83% were White, 53% were female, and over half reported attending college or technical school. Individuals with cancer of internal organs had higher rates of cancer treatment refusal at 8.43%, compared with 4.41% for breast cancer, 5.94% for skin cancer, and 4.15% for other types. Individuals who did not graduate high school were nearly twice as likely to refuse cancer treatment than other education groups (11.57%; P <.01).

Conclusion: Our investigation contributes to the literature as it brings awareness to the sociodemographic disparities in cancer treatment refusal rates, allowing future research to focus on these groups. Focused efforts on educating these groups may improve cancer screening rates and treatment awareness, thus increasing cancer survival rates.

More than 1.6 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year.1 According to a CDC report, cancer mortality decreased 27% from 2011 to 2020.1 Despite this decrease, cancer is still the second leading cause of death worldwide. Thanks to technological advances in medicine, many options are available for treatment, including chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy, thermal ablation, immunotherapy, photodynamic therapy, stem cell transplant, and surgery.2 Many factors are taken into consideration by patients when deciding whether to seek treatment. Cost can be a major factor in a patient’s decision on whether to receive treatment. The economic burden of cancer was over $21 billion, which included patient out-of-pocket costs and patient time costs—time off from work, transportation costs, room and board, waiting for and receiving care—in 2019 alone.3 The relationship between financial burden and the ability to undergo cancer treatment has been previously demonstrated.4 In addition to cost, personal beliefs and sociodemographic variables such as age, race/ethnicity, gender, and educational attainment are important considerations when deciding on cancer treatment.

Few studies exist that examine cancer treatment refusal. Dias and colleagues found older patient age to be one of the strongest predictive factors associated with cancer treatment refusal.5 The study also showed other factors associated with treatment refusal, including female gender, being of a non-White race, having government insurance or no insurance, and being unmarried.5 A systematic review by Puts and colleagues showed that reasons for declining treatment included fear of side effects, unclear benefits of the treatment, feeling too old for treatment, financial reasons, and physician lack of communication or distrust.6 Furthermore, the importance of patient–physician communication and shared decision-making has been shown to be of the utmost importance.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess population-based sociodemographic characteristics of individuals who refuse or delay cancer treatment in the United States. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a publicly available data set that collects state-level data about chronic health conditions, use of preventive services, and health risk behaviors.7 Our primary objective was to use BRFSS to quantify the number of individuals who refuse or delay treatment by cancer type and conduct a demographic analysis of these individuals. Secondarily, we aimed to assess whether individuals who refuse or delay cancer treatment have different levels of pain compared with those who receive treatment.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study using the BRFSS data from 2017 to 2020 to analyze the prevalence of individuals who refuse or delay cancer treatment by type of cancer and group characteristics, as well as differences between individuals refusing cancer treatment compared with those currently receiving treatment. We then used the 2020 BRFSS data to assess whether those refusing or delaying treatment had a difference in pain level compared with those receiving treatment. BRFSS is a system of telephone surveys collecting state-level data about many public health behaviors of US adults, as well as their demographic information.7 It was established in 1984 and now collects data in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and US territories. The data allow researchers and physicians to make informed decisions on (1) identifying high-risk populations for chronic health conditions, (2) monitoring changes in disease rates and health risk behaviors, and (3) establishing disease prevention strategies.7

First, we reported the prevalence rates of individuals in each category. We then estimated the population-based demographic based on age, race/ethnicity, gender, and education and on subgroups of cancer type.

Eligibility/Inclusion

We analyzed BRFSS data to examine the number of patients who elect to refuse or delay treatment by cancer type and sociodemographic variables. To assess characteristics of those who refused cancer treatment, we included BRFSS respondents who answered affirmatively to the prompt “Do you have cancer?” and subsequently answered “Are you currently receiving cancer treatment?” with choices of “currently receiving treatment,” “refused treatment,” or “am waiting for treatment.” Respondents who answered “unsure” or were marked as missing were excluded from this study.

Cancer-Related Variables

We analyzed the prevalence of refusal or delay in cancer treatment by cancer type from the 2017-2020 BRFSS data. Cancer types included: (1) breast, (2) internal organs, (3) skin, and (4) other (blood, bone, head/neck, and other). For 2020 BRFSS data only, individuals diagnosed with cancer were divided into 3 groups: (1) receiving treatment, (2) refused treatment, and (3) waiting for treatment, and we nalyzed whether they were experiencing pain.

Demographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables extracted from BRFSS and reported in our investigation as controls were gender (male or female), education (less than high school, high school graduate or GED, some college, college graduate or higher), and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Native American, Hispanic, and other).

Statistical Analysis

First, we reported the prevalence rates of individuals in each category. We then estimated the population-based demographic based on age, race/ethnicity, gender, and education and on subgroups of cancer type. We tested for associations between these groupings using design-based chi-square tests. Then, using the 2020 data, we constructed logistic regression models to assess the associations, via odds ratios, between cancer treatment groups and whether they were experiencing cancer-related pain. Survey design and sampling weights, provided by BRFSS, were employed for all analyses. Alpha was set at .05, and analyses were conducted in Stata 16.1.

Results

Using the BRFSS data from 2017-2020—after excluding individuals with no history of cancer and those who had completed treatment—our sample size (n) was 6238, which represents a weighted population estimate of 544,641 (N). We also used the BRFSS data from 2020 to identify a sample size (n=2408), which represented a population (N=225,257).

Sociodemographics

Our sample primarily included White individuals (83.29%) followed by Black individuals (9.55%) and Hispanic individuals (3.60%; Table 1). The majority of our sample was female (53.03%). Over half of our sample reported having some college/tech education or graduated from college. The mean age of all participants was 64.09 years.

Cancer Treatment Status and Associations

Individuals with cancer of internal organs had higher rates of cancer treatment refusal at 8.43%, compared with 4.41% for breast cancer, 5.94% for skin cancer, and 4.15% for other types (Table 1). Breast cancer showed to have the most patients undergoing treatment (86.33%) compared with the other cancer types. However, skin cancer was almost twice as likely to have patients awaiting cancer treatment (31.82%) when compared with other cancer types (P<.001). All minority races/ethnicities were significantly less likely to be waiting for treatment, with Asians being the least likely (7.71%), followed by Hispanics (14.93%) and Whites (25.42%; P=.004). Individuals who did not graduate high school were almost twice as likely to refuse cancer treatment than other education groups (11.57%; P=.002). No statistically significant association was observed between cancer treatment status and gender.

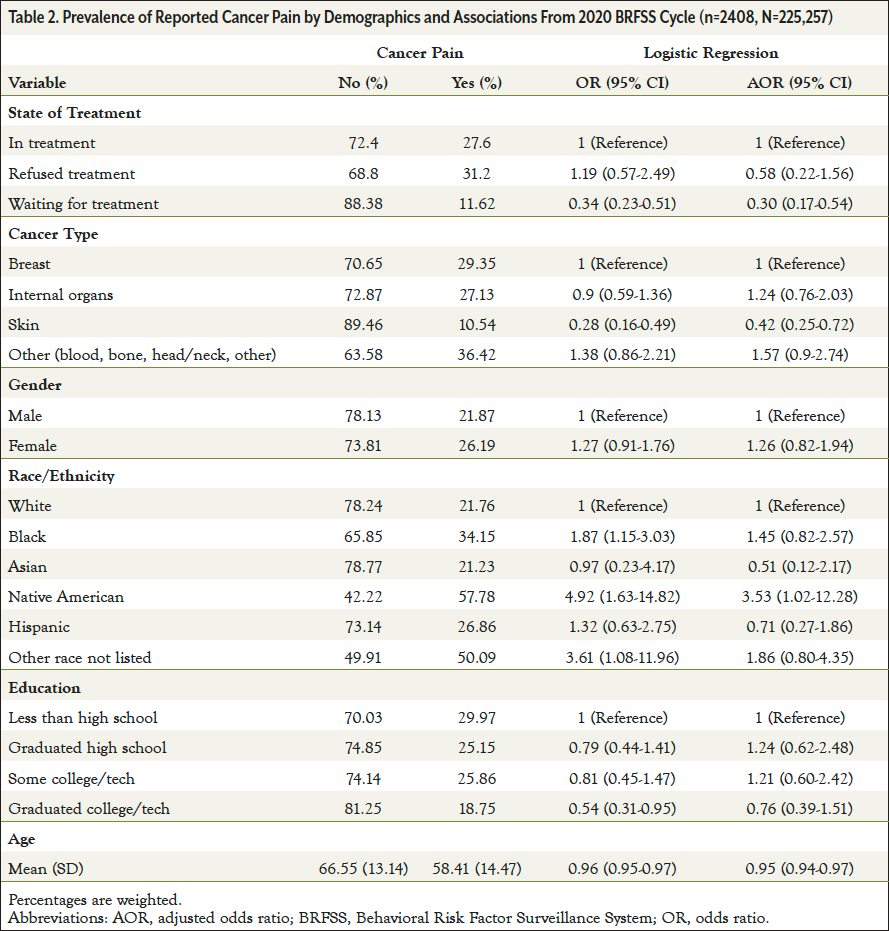

Cancer Pain

Among individuals with cancer, those waiting for treatment were significantly less likely to report experiencing cancer-related pain (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.30; 95% CI, 0.17-0.54) compared with those currently receiving treatment (Table 2); however, those refusing cancer treatment did not significantly differ in the likelihood of reporting cancer-related pain. Compared with breast cancer, individuals with skin cancer were significantly less likely to report cancer-related pain (AOR=0.42; 95% CI, 0.25-0.72). Native American individuals were significantly more likely to report cancer-related pain compared with White individuals (AOR=3.53; 95% CI, 1.02-12.28). Individuals reporting cancer pain were on average younger (58.41 years) than those reporting no cancer pain (66.55 years), revealing a statistically significant difference (AOR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.94-0.97). There were no statistically significant results for gender or education level with cancer-related pain reporting.

Discussion

Our investigation revealed statistically significant relationships between individuals who refused cancer treatment by race and cancer type. In addition, individuals who did not complete high school had cancer refusal rates that were nearly double all other education groups. Among individuals diagnosed with cancer, those who refused treatment had no significant difference in reporting cancer-related pain when compared with those who were currently receiving treatment. However, individuals waiting for treatment were significantly less likely to report pain compared with the in-treatment group. Previous studies have shown similar results regarding low education levels and refusing cancer treatment.5,8 Cancer treatment refusal in these individuals could be due to a lack of knowledge, poor access to healthcare, delayed diagnosis resulting in reduced treatment responsiveness, or lower socioeconomic status.5,9,10

Low educational attainment is associated with more chronic conditions, functional limitations, and disability leading to worse overall health.11 One study showed that higher education was associated with higher health literacy scores.12 These findings lead to concern for low health literacy in individuals with lower education levels. Low health literacy has been shown to be associated with individuals who are older, have limited education, are minorities, and have lower income,13 which is in agreement with our results. Therefore, individuals refusing cancer treatment might be doing so due to lower health literacy, a hypothesis supported by a worldwide systematic review that showed an increased risk for delayed diagnosis of cancers in patients with low educational attainment.14 A study by Busch and colleagues showed that individuals with higher health literacy were more likely to receive chemotherapy when diagnosed with stage III/IV cancer; however, there was no difference in health literacy regarding cancer stage at diagnosis.15 Further, a systematic review evaluating 60 papers in the field of oncology found that higher health literacy was also associated with increased odds of adjuvant chemotherapy for late-stage colon cancer,16 showing that those with higher health literacy were more likely to receive treatment. It has been demonstrated that individuals with low health literacy are significantly less likely to have heard of multiple cancer screening tests—colonoscopy, mammogram, prostate-specific antigen—or even identify the type of cancer associated with each test.14 These individuals were also more likely to discuss cancer prevention with a healthcare provider rather than seeking out information regarding their health online.14

Individuals waiting for treatment were significantly less likely to report pain compared with the in-treatment group. Previous studies have shown similar results regarding low education levels and refusing cancer treatment.

Treatment refusal has also been shown to be associated with diagnosis of advanced-stage disease.5 The Annals of Palliative Medicine reviewed and analyzed multiple studies that showed the most common reason for the refusal of cancer treatment was the presence of stage III or IV disease.5 Lower socioeconomic positions have also been shown as risk factors for late-stage diagnosis and increased mortality in individuals with cancer.17 Socioeconomic status has been related to health literacy, which often equates to increased financial burden from cancer treatment and worse quality of life.16 We also found a significant association between cancer treatment groups, with racial/ethnic minorities more often refusing cancer treatment than White individuals. These results are supported by Wolf and colleagues, who found that African Americans were diagnosed with more advanced-stage cancer compared with White individuals.18 Cancer death rates for all cancers are higher in Black individuals followed by White individuals, while death rates are lowest in Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals.19 In addition, cancer mortality has been shown to be significantly higher in those with low education levels compared with those with higher education levels.20 Thus, increasing patient education in those with low health literacy may lead to improvement in both cancer screening and cancer treatment uptake. An article written by family physician Dr Moshe Frenkel documented that a patient, who was also a physician, was diagnosed with stage IIIB ductal carcinoma.21 After reviewing and finding that cancer survival rates with and without treatment were similar for her diagnosis, the patient ultimately decided to refuse treatment to preserve her quality of life.21

Recommendations

Cancer screening modalities allow for prevention or early detection of malignancy.22 Individuals with low health literacy may not be aware of these screening modalities or recommendations. It is of the utmost importance for physicians to be more aware of how to identify which patients are in need. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit can help increase patient understanding of their health and provide them with proper support based on their health literacy.23 This toolkit provides physicians with resources to improve communication with their patients. It also provides physicians with resources to be able to identify affected patients and provide them with resources to improve health literacy and access to both medical and nonmedical assistance programs.23 Increasing both physician awareness and implementation of this toolkit may help increase health literacy awareness and thus lead to its improvement.

Another way to increase cancer screening could be through the use of community-based programs. One study found that most women using mobile mammography units were racial/ethnic minorities who did not have insurance and were low income.24 These users also had lower adherence to the screening guidelines.24 A study by Drake and colleagues used funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to improve access to mammograms and reduce out-of-pocket cost through the use of patient navigators in underserved areas.25 Prevention Care Management was a telephone-based program designed to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening among women aged 50 to 69 years.26 By addressing barriers to screening, there was a significant increase in screening uptake among participants in all screening categories.26 In addition, a Community Cancer Screening Program in south Georgia showed that among low-income, underinsured, and uninsured patients aged 50 to 64 years, colon cancer screening uptake and compliance were significantly higher in participants than nonparticipants.27

Patient navigators could be a vital component of the success of community-based programs. Navigators should recognize the at-risk populations and help educate patients on needed health and cancer screenings to improve adherence to guidelines. Therefore, increasing implementation of community-based cancer screening programs could further increase uptake and decrease cancer incidence and, thus, cancer treatment refusal.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations to our study include that all data were collected via survey and were self-reported, which could introduce a recall bias. However, BRFSS is a nationally recognized telephone survey system that completes over 400,000 interviews annually, making it the largest in the world.28 Secondly, our study was cross-sectional in nature, so our findings are correlational rather than causal and should be interpreted as such. Thirdly, the calculated gender variable in BRFSS is binary; however, they do collect data if a participant identifies as transgender, but this has only been adopted by a few states, thus making it currently infeasible to use for this sample. Raw data from our sample show 28 participants out of 6238 identified as transgender. Finally, this study did not include stage of cancer diagnosis, reason for treatment refusal, or specific cancer types (eg, pancreatic, multiple myeloma), all of which directly influence a patient’s reasoning for treatment refusal. Future research should focus on determining the best evidence-based strategies and implementation of community-based programs to improve cancer screening, treatment awareness, and uptake. Additional efforts should focus on improving health literacy among groups with higher cancer refusal rates, which may, in turn, lead to improvement in cancer treatment refusal rates.

Conclusion

Our investigation was performed to identify and highlight sociodemographic differences in patients who choose to refuse or delay cancer treatment. It can contribute to the literature as it can bring awareness to the sociodemographic disparities in cancer treatment refusal rates, allowing future research to focus on these groups. Focused efforts to better understand why patients are refusing treatment may inform structural remedies to treatment refusal and patient education. Educating these groups may improve cancer screening rates and treatment awareness, thus increasing cancer survival rates.

Funding: This study was not funded.

Acknowledgements: Dr Hartwell receives research support through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grants R41MC45951 and U4AMC44250-01-02.

Conflicts of Interest/Declarations: Dr Hartwell receives research support through the National Institute for Justice and Health Resources Services Administration—unrelated to the current work.

Ethical Statement: This study was determined to be nonhuman subjects research by the Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An Update on Cancer Deaths in the United States. www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/research/update-on-cancer-deaths/index.htm. Updated February 28, 2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- National Cancer Institute. Types of Cancer Treatment. www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types. Published July 31, 2017. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- National Institutes of Health. Annual Report to the Nation Part 2: Patient economic burden of cancer care more than $21 billion in the United States in 2019. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/annual-report-nation-part-2-patient-economic-burden-cancer-care-more-21-billion-united-states-2019. Published October 26, 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:153-165.

- Dias LM, Bezerra MR, Barra WF, Rego F. Refusal of medical treatment by older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:4868-4877.

- Puts MTE, Tapscott B, Fitch M, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing older adults’ decision to accept or decline cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:197-215.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/fact sheets/brfss.htm. Published April 1, 2019. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- Suh WN, Kong KA, Han Y, et al. Risk factors associated with treatment refusal in lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2017;8:443-450.

- Hu X, Ye H, Yan W, Sun Y. Factors associated with patient’s refusal of recommended cancer surgery: based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Front Public Health. 2022;9:785602.

- Etminani R, Kan C, Mozaffarian L. Investigating the role of transportation barriers in cancer patients’ decision making regarding the treatment process. Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2021;2675(6):175-187.

- Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:273-289.

- Jansen T, Rademakers J, Waverijn G, et al. The role of health literacy in explaining the association between educational attainment and the use of out-of-hours primary care services in chronically ill people: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:394.

- Hickey KT, Masterson Creber RM, Reading M, et al. Low health literacy: implications for managing cardiac patients in practice. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:49-55.

- Baccolini V, Isonne C, Salerno C, et al. The association between adherence to cancer screening programs and health literacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2022;155:106927.

- Busch EL, Martin C, DeWalt DA, Sandler RS. Functional health literacy, chemotherapy decisions, and outcomes among a colorectal cancer cohort. Cancer Control. 2015;22:95-101.

- Holden CE, Wheelwright S, Harle A, Wagland R. The role of health literacy in cancer care: a mixed studies systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259815.

- Sorice KA, Fang CY, Wiese D, et al. Systematic review of neighborhood socioeconomic indices studied across the cancer control continuum. Cancer Med. 2022;11:2125-2144.

- Wolf A, Alpert N, Tran BV, et al. Persistence of racial disparities in early-stage lung cancer treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:1670-1679.e4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health, United States, 2020-2021. Cancer Deaths. www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/topics/cancer-deaths.htm. Accessed October 21, 2022.

- Ma J, Siegel RL, Islami F, Jemal A. Temporal trends in liver cancer mortality by educational attainment in the United States, 2000-2015. Cancer. 2019;125:2089-2098.

- Frenkel M. Refusing treatment. Oncologist. 2013;18:634-636.

- Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A. Cancer prevention and screening: the next step in the era of precision medicine. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2019;3:3.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, 2nd Edition. www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/toolkit.html. Accessed October 10, 2022.

- Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Mobile mammography participation among medically underserved women: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E140.

- Drake BF, Tannan S, Anwuri VV, et al. A community-based partnership to successfully implement and maintain a breast health navigation program. J Community Health. 2015;40:1216-1223.

- National Cancer Institute. Prevention Care Management. https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/programDetails.do?programId=295722. Accessed October 11, 2022.

- National Cancer Institute. Community Cancer Screening Program (CCSP). https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/programDetails.do?progr amId=24355707. Accessed October 11, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html. Accessed September 28, 2022.