Mandi L. Pratt-Chapman, PhD1,2; Hannah Arem, PhD3,4

1Department of Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

2GW Cancer Center, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

3Healthcare Delivery Research, MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, DC

4Department of Oncology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Background: During the COVID-19 pandemic, many cancer care services were delayed. Studies have documented increased distress and physical impacts on cancer survivors during the pandemic. Our study describes access to healthcare challenges, worry of COVID-19, health and social changes, and quality of life (QOL) among cancer survivors approximately 6 months into the pandemic, with specific focus on time since diagnosis.

Methods: The Cancer Survivor Experiences with COVID-19 Survey was fielded from October 8 to November 6, 2020. We recruited cancer survivors (N=535) primarily through institutions accredited by the Commission on Cancer and other collaborating organizations. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Related Quality of Life in Cancer Patients and Survivors scale and the 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) scale were used to assess levels of anxiety and QOL. Severity of fear and QOL impact were reported using descriptive statistics. Analysis of variance was used to examine differences in challenges obtaining medical care for comorbid conditions, COVID-19 worry, and SF-12 mean scores by time from diagnosis. Content analysis was conducted on open-ended questions.

Results: Most respondents indicated their cancer was in remission or had no evidence of disease (79%). One-quarter of the respondents were able to work from home, while approximately one-fifth could not work or had lost their job. Declines in physical (27%), emotional (39%), spiritual (19%), and sexual (13%) health were reported. Moderate worry about COVID-19 and moderate QOL scores with worse mean scores for survivors 2 to 5 years from diagnosis compared with those diagnosed within 2 years or longer than 5 years were reported.

Patients with a history of cancer have unique health risks from COVID-19 compared with the general population. A systematic review of studies of COVID-19 among cancer patients compared with the general population showed that cancer was significantly associated with severe COVID-19 adverse events,1 including a nearly 3-fold increase in risk of death compared with those without cancer. Patients with hematological malignancies have been shown to have a greater risk for more severe COVID-19 compared with patients in treatment for solid tumors.2 Most extant studies on cancer and COVID-19 have focused on patients in active treatment.3-5 A smaller number of studies have examined the impact of the pandemic on posttreatment survivors.6-8 Findings from these studies suggest that cancer survivors in the United States experienced social isolation and mental distress as a result of the pandemic,9 as well as delays to medical care.10 Despite the vast amount of information gathered from prior literature, there have been limited data about the effects of the pandemic on survivors based on time since diagnosis.

To contribute to knowledge about the experiences of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic, we aimed to capture self-reported changes in cancer survivors’ physical and mental health, challenges in obtaining care, fear of COVID-19, and employment and social changes approximately 6 months into the pandemic. We also assessed differences by time since diagnosis.

Methods

Data Collection

Respondents were asked 2 screening questions to confirm eligibility: whether they had ever had a cancer diagnosis, and whether they resided in the United States. A series of additional questions were embedded to reduce the risk of fraudulent responses or bots.11 Informed consent was indicated by checking a box and continuing on to respond to survey questions. The survey was offered in English, Spanish, French, and Chinese.

Respondents completed an 88-item questionnaire, previously published,12 which included questions about demographics (ie, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, partnership status, education, employment status, insurance type, and household size and income) along with adapted measures from the literature. Measures included the unpublished Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) in Cancer Patients and Survivors scale (accessible on PhenX toolkit), the Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale, the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire, and the 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12). For surveys that used Likert scales, scales were eliminated and checklists were incorporated to reduce the length of the survey. For the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and HRQOL in Cancer Patients and Survivors scale,13 5 items were added to measure positive responses to the pandemic. The Preparing for Your Doctor’s Visit worksheet from the Advancing Patient-Centered Cancer Survivorship Care Toolkit14 was used to ask about whether physical health, emotional health, spiritual health, sexual health, relationships, ability to do things, employment, finances, and insurance coverage had gotten better, worse, or not changed since the start of the pandemic.

Respondents were also asked if they or friends or family members had been diagnosed with COVID-19. An open-ended question asked participants to share any additional comments of their experiences as a cancer survivor during the pandemic to inform future improvements to cancer survivorship care.

Participant Recruitment

A survey was fielded from October 8 to November 6, 2020. The Commission on Cancer requested that cancer registrars at its accredited cancer centers forward the survey link and sample messaging to a Survivorship Coordinator to facilitate dissemination of the survey to cancer survivors. Participants were also recruited through the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Association of Oncology Social Work, GW Cancer Center professional listservs, Boston University’s Translating Research Into Practice research team, and CDC National Networks that provide technical assistance to diverse minoritized racial, ethnic, and sexual and gender subgroups.

We originally received 1977 responses. However, patterns of responses prompted the study team to systematically investigate potential false responses and bots; this analysis has been published elsewhere.11 After applying extensive data quality checks, our final sample was N=535.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize major survey domains. For the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and HRQOL in Cancer Patients and Survivors scale, the 5 items added to measure positive responses to the pandemic were reverse coded before summing the scale for a continuous variable (range, 0-20). Higher scores indicated greater worry.

The SF-12 scale was calculated from 12 variables that asked participants to rate their physical and mental health. Four items were reverse scored, so that lower scores for all items indicated better health (range, 0-35). Because we chose to use linear scoring, which has been shown to be a reasonably accurate means of interpreting results from the scale, the directionality of our data (lower scores equal better health) is the inverse of that for studies using the SF-12 with weighted scoring.15

We examined associations in the self-reported experiences by time from diagnosis. We also conducted content analysis to describe themes from open-ended feedback.

Results

Participant Characteristics

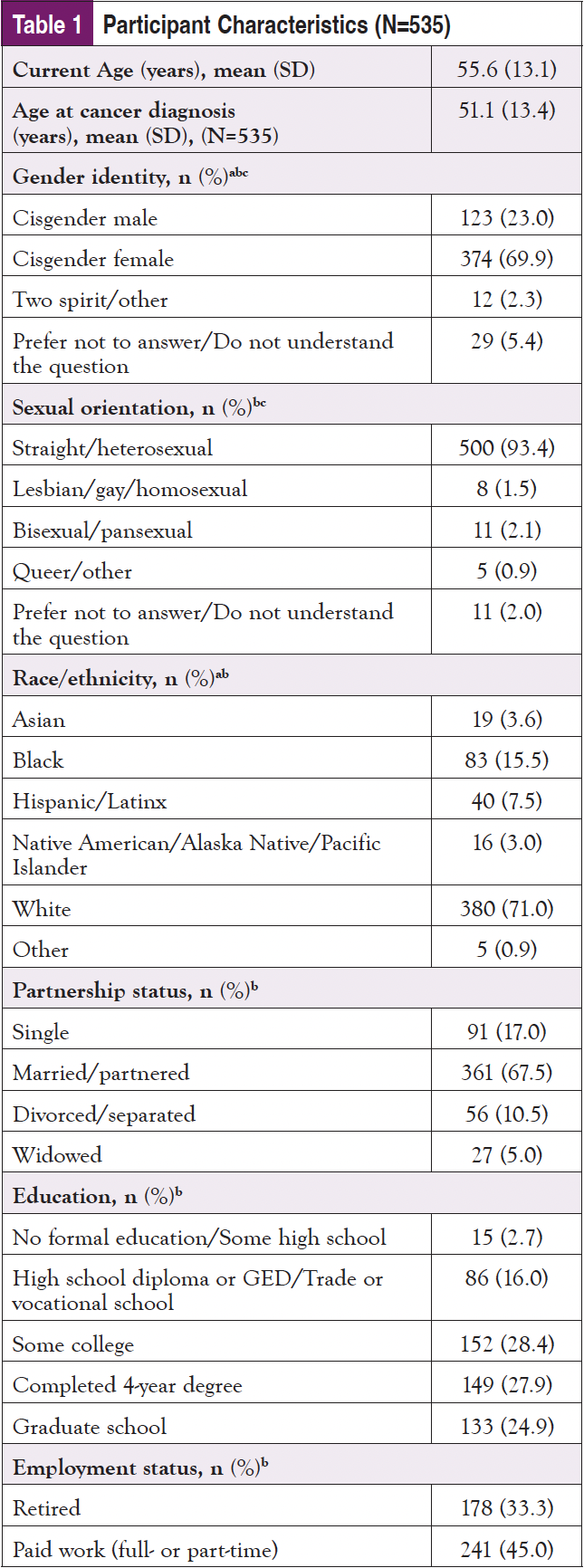

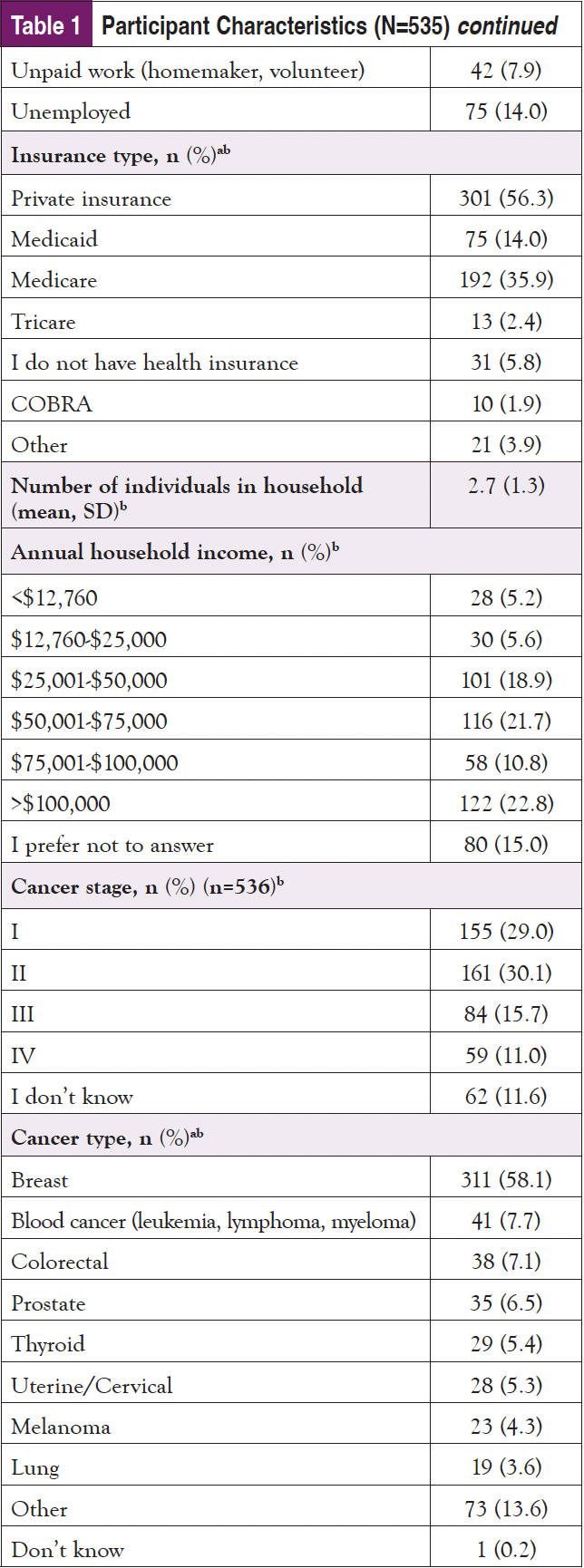

Participants represented 43 states and the District of Columbia in the United States. Approximately 7% of the sample reported being part of a tribe or territory (n=36). Our population was on average age 55.6 years (SD=13.1). The sample primarily identified as cisgender female (70%), straight/heterosexual (93%), White (71%), and married or partnered (68%). Most of the participants were employed part-time or full-time (45%) or retired (33%). Level of education, type of insurance, and household income varied widely. The most common diagnoses reported were cancers of the breast (58%), hematologic (8%), colon or rectum (7%), and prostate (7%). Cancer stages at diagnosis were most commonly stage I (29%) or II (30%), with most respondents indicating that their cancer was in remission or they had no evidence of disease (79%) (Table 1).

Descriptive Statistics and Exploratory Analysis

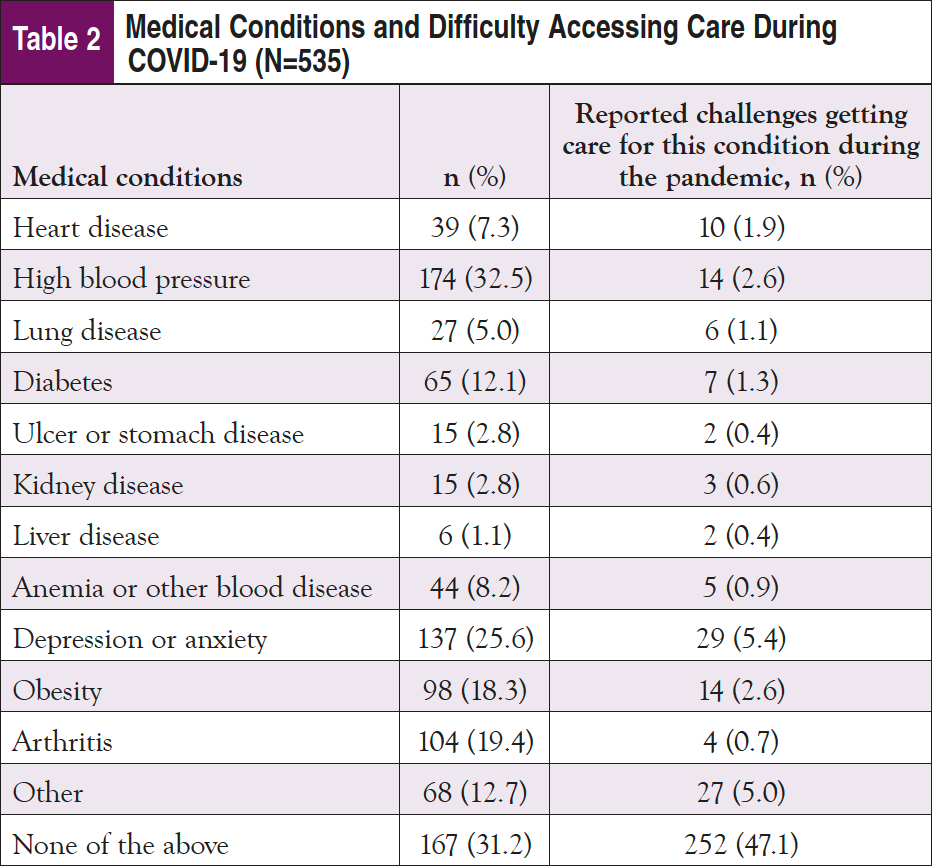

More than half of the sample reported at least 1 comorbid condition, the most common being high blood pressure (33%) followed by depression or anxiety (26%). While approximately half of participants reported that they did not have any challenges getting care, nearly a quarter reported challenges getting access to care for their comorbid condition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression or anxiety was the most common condition reported in terms of challenges in obtaining needed care during the pandemic (Table 2).

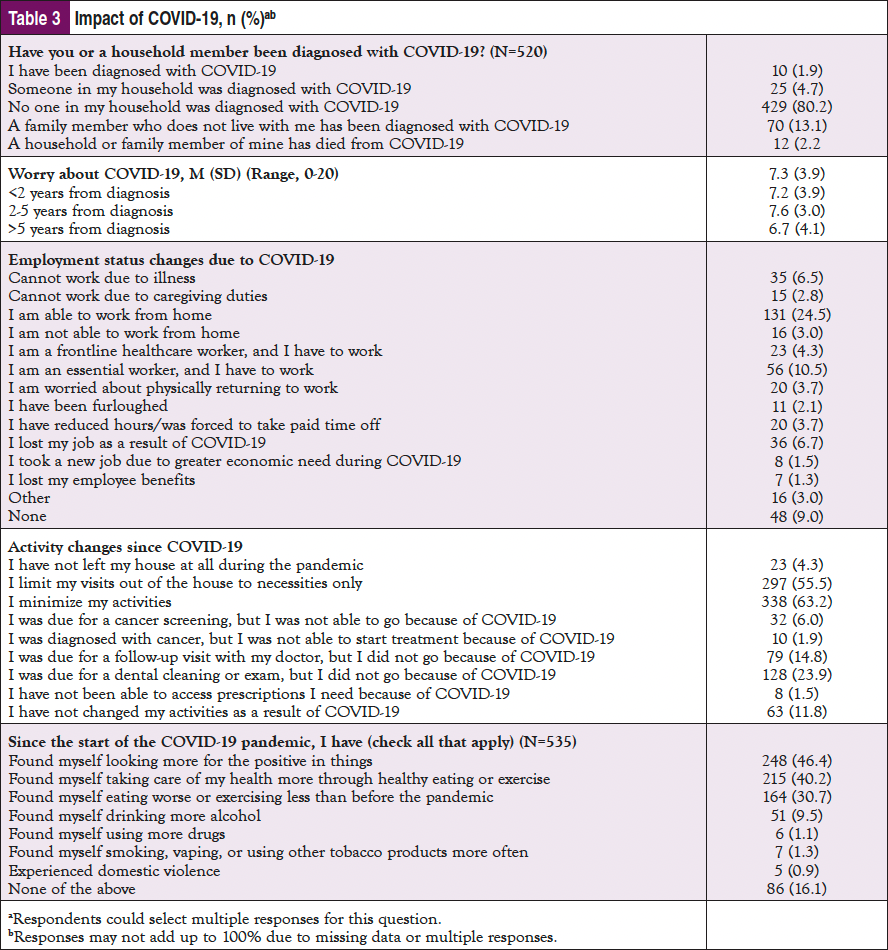

At the time of survey completion, 80% of participants indicated that no one in their household had been diagnosed with COVID-19, 13% indicated that a family member who did not reside with them had been diagnosed, 2% indicated a family member had died of COVID-19, and 2% reported having been diagnosed with COVID-19.

When asked about worry about COVID-19, the mean score was 7.3 (SD=3.9) with a range of 0-20 (lower scores mean less worry). Notably, a third of the sample (34%) indicated optimism that a vaccine would arrive soon, and 45% reported hope that the pandemic would end soon (data in text only). Cancer survivors between 2 and 5 years postdiagnosis (n=155) reported statistically significantly more worry (M=7.6, SD=3.9) than peers in the groups with either less than 2 years (n=225) (M=7.2, SD=3.9) or more than 5 years (n=134) (M=6.7, SD=4.1) since diagnosis (F[2, 511]=8.0, P<.01) (Table 3).

When asked about employment changes since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a quarter of the respondents indicated the ability to work from home, while 11% were essential workers. Approximately 10% of respondents lost their job, were furloughed, or lost employee benefits during the pandemic, and another 9% could not work due to illness (Table 3).

The majority of respondents (63%) indicated that they had minimized activities since the pandemic began, with over half (56%) indicating limiting activities out of the house to only necessities. Almost half of the sample indicated not getting necessary healthcare, including dental cleaning (24%), cancer care follow-up (15%), cancer screening (6%), cancer treatment (2%), and prescriptions (2%). A minority (12%) reported being unaffected in their activities as a result of the pandemic.

In terms of coping, almost half of the sample (46%) endorsed looking for the positive in things since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately 40% indicated taking better care of their health through nutrition and exercise, while approximately 31% reported doing the opposite since the start of the pandemic. Approximately 10% reported drinking more alcohol, and a small percentage (1%) reported using more drugs or tobacco since the start of the pandemic. One percent also reported experiencing domestic violence during the pandemic. Less than a fifth of respondents indicated they were unaffected behaviorally as a result of the pandemic (Table 3).

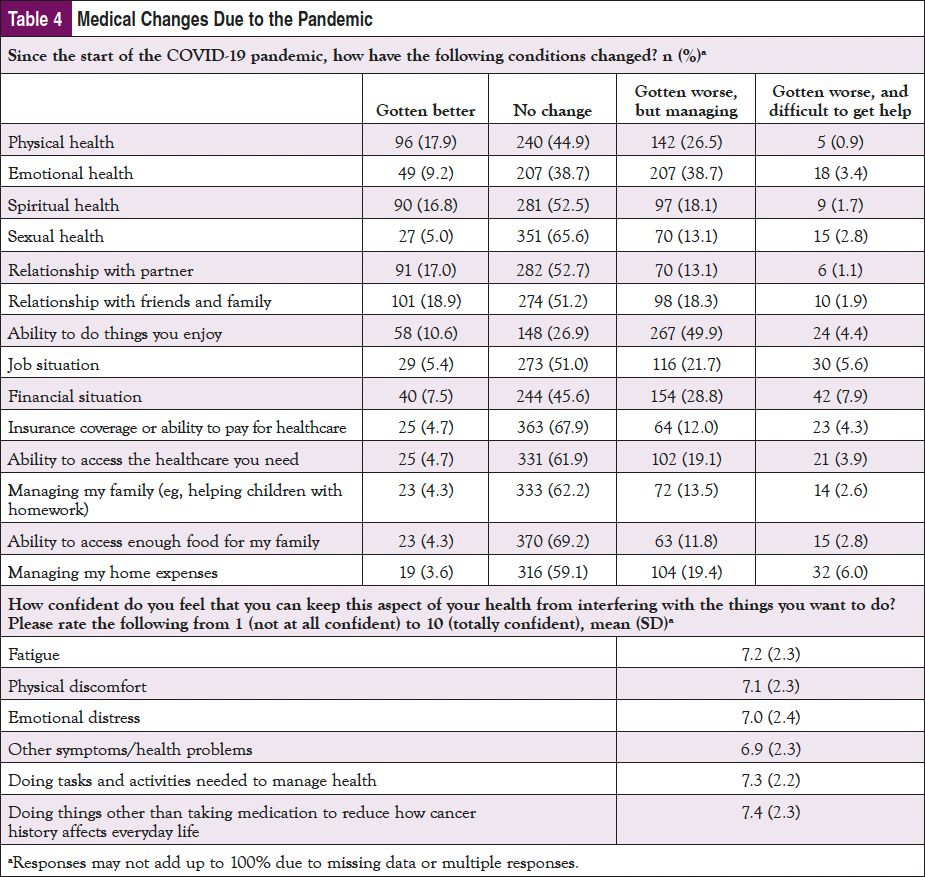

For quality of life (QOL), more than one-quarter of participants indicated that their physical health had worsened since the start of the pandemic, and 39% reported worse emotional health (Table 4). Nearly half indicated their ability to do things they enjoyed was impaired since the start of the pandemic. Over a fifth of respondents said their job situation and financial situation had worsened, and they had difficulty managing household expenses. A minority of respondents indicated they could not get help for these challenges, and mean scores indicated an above average level of confidence that respondents could manage their physical health. For the summed SF-12, the mean score was 14.2 (SD=6.8; range, 0-35), and cancer survivors between 2 and 5 years postdiagnosis had statistically significantly lower QOL (M=15.3, SD=6.5) than peers in the group with either less than 2 years (M=14.3, SD=6.8) or more than 5 years (M=12.5, SD=6.8) since diagnosis (F[2, 511]=5.6, P<.01) (data in text only). In addition, COVID-19 worry and QOL were statistically significantly correlated (P<.001) (data in text only).

Open-ended feedback indicated 2 major themes: the detrimental impact of social isolation and the need for continued cancer survivorship care services. One respondent indicated that isolation during the pandemic made treatment more difficult:

The hardest part has been actual physical and emotional connection with people. Isolation is a very depressing. Before COVID the best and most successful part of my cancer treatment was being able to connect with other people. Share the good times and the bad. Mental health to me is the BIGGEST obstacle in overcoming cancer.

Another respondent said:

Although we have been able to participate in our support group through Zoom, it is just not the same as meeting in person. Wish there was a way to provide a safe environment where we could be socially distance, but still meet in person.

Others voiced similar frustrations, but also voiced appreciation for the healthcare team:

Not being able to have family members or friends share in the experience of chemo/going to appointments was initially difficult, but I found it peaceful attending these appointments alone, in that I was able to find time for myself and meet others in the same situation. The nurses and doctors have made it a wonderful process!!!

Another respondent agreed, saying:

My diagnosis came March 13, 2020. My husband was not allowed to accompany me to any medical appointments or my surgery. I was scared to death and alone! BUT all the medical associates I dealt with were awesome and caring. And shutting down made me feel so much safer from getting COVID-19.

Finally, another respondent recommended “social interactions for those living alone.”

The second theme was the importance of obtaining necessary survivorship care services. One person said:

Others are sicker than I am, but that doesn’t mean I don’t need services, too.

Another person reported:

Missing an important 3-month cancer checkup had severe consequences. I wish someone from my cancer team had called and told me to at least get bloodwork done in May.

A third respondent said:

My care team and I were monitoring an enlarged lymph node for the first 2 months of the pandemic. We were hesitant to get scans or surgery given COVID, but after months of waiting, decided to proceed. COVID made a very anxiety-provoking time even worse, almost unimaginable. As someone in remission, I have felt even more so during the pandemic that I am low priority for oncology providers. Survivorship is always last on the list and during a time of crisis, I worry that very little attention is being paid to it.

In contrast, those in need of more urgent treatment were able to access services. One person said:

I was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer a few months prior to the pandemic so I have had many [doctor] appointments. I was very hesitant about going to the cancer center and lab at first, but they have done a great job keeping everyone safe.

Another indicated:

I was diagnosed with MBC-triple positive in Dec 2019 and was responding well to treatments when COVID-19 took off. I’ve continued treatments to stay alive so I had to have faith that the providers were doing what they could to keep us safe.

Collectively, open-ended feedback indicated trust in the healthcare team and distress about delayed survivorship care and social isolation.

Discussion

Our study supports prior studies showing the negative impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on cancer survivors’ physical and mental health,9,16 daily activities,17 and QOL.16 Several studies have shown heightened distress due to fear of COVID-19 and fear of delays to cancer care as a result of the pandemic. Early in the pandemic (May-June 2020), one study reported low levels of cancer patient anxiety.16 However, studies capturing survivor experiences after the pandemic had been endured for many months (May-October 2020) showed heightened anxiety compared with levels before the pandemic began.18 Some studies indicated greater distress among those with advanced disease.19 Results have been mixed in terms of outcomes stratified by sex or age.3,18,19 Prior studies were limited in their attention to effects on survivors based on time since diagnosis.

Our study directly follows the timing of these previous studies by surveying cancer survivors October-November 2020, reporting impact on cancer survivors as the pandemic lingered. Almost half of survivors reported worse physical health, and nearly 40% reported worse emotional health. Over half reported worse spiritual health (53%), worse sexual health (67%), and deteriorating relationships with their partner (53%) and with friends and family (51%). Contrary to other studies showing decreased physical activity of cancer survivors during the pandemic,20,21 our study suggests that more cancer survivors (40%) reported being more conscious of healthy eating and exercise than those who reported worsening health behaviors (31%). More than 30% of respondents in our sample indicated adverse employment impacts of COVID-19. These findings align with other studies showing the impact of unemployment and reduced hours among cancer survivors during the pandemic.22 Loss of work during the pandemic has been linked to reduced access to treatment and higher mortality.22 Similar to published studies, our sample reported a high level of disruption in daily activities, social isolation,23 and loneliness.9 Over 63% of our sample indicated they had minimized activities, and over half indicated they go out of the house only for necessities. Open-ended feedback confirmed the impact of social isolation and not having support during appointments.

In addition, when asked about delays to healthcare, only 6% of the sample indicated delays in cancer screening, and less than 2% reported delays to the start of cancer treatment, but 15% said that follow-up care posttreatment had been delayed. Given known delays to cancer screening and diagnoses nationwide, these results are likely due to the greater frequency of recommended cancer follow-up care compared with general cancer screening among cancer survivors. These findings have important implications for the provision of longitudinal cancer survivorship care.

A contribution of our study is the differences reported among survivors at various years from diagnosis. While survivors of all time periods since diagnosis reported moderate worry of COVID-19 and moderate QOL, survivors between 2 and 5 years from diagnosis had statistically significantly greater worry and worse QOL compared with peers who had been diagnosed less than 2 years from the time of survey completion or more than 5 years. This is a critical finding, since some past studies (outside of a pandemic context) have reported poorer QOL of breast cancer survivors less than 2 years since diagnosis24 and individuals living with chronic cancer,25 but similar QOL of cancer survivors and peers without a history of cancer after 2 years.24 Our results suggest that the pandemic may have created a greater disruption of supportive care services for survivors 2 to 5 years postdiagnosis compared with those more readily seen for treatment (less than 2 years since diagnosis) or those with a longer period of time to adjust to changes since cancer treatment (those more than 5 years from diagnosis). Open-ended feedback supports this interpretation, since patients in need of immediate surgery and chemotherapy reported being able to receive services, while those who were further from treatment voiced more frustrations in care delays. Those far from diagnosis reported feeling similar to noncancer peers. One respondent said, “Since I am 10+ years out, the impact has been about the same as it has for noncancer people, just living life day by day and listening to the experts as to how to protect ourselves for exposure.”

Limitations of our study include a convenience sample from snowball sampling. Our sample demographics also do not reflect the diversity of lived experiences of those in the United States. Despite translating the survey into 4 languages and disseminating the survey through numerous community partners, our sample was predominantly White, cisgender female, straight/heterosexual, and had a history of breast cancer. These demographics limit the generalizability of our findings. Our study is also limited by data captured only at a single point in time.

Strengths of our study include that it was completed by participants in diverse geographies nationwide and captured a wide range of social and emotional, as well as practical implications of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Given the length of the pandemic, cancer survivors are likely to suffer from exacerbated mental and physical health effects for some time. Understanding patient concerns and QOL during this health crisis will be crucial to allocating resources and focusing resources and interventions on those who need them most. Importantly, our study suggests that those who have completed cancer treatment but are within 5 years of diagnosis may have significant unaddressed healthcare and social care needs. Long-term implications of these effects and interventions to address them are needed.

Author Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, contract #EADI-12744.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jenna Moses for data management support and Ruta Brazinskaite for logistical support. Thank you to advisory board members Megan Slocum, Sara Field, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Maureen Killackey, Shelley Fuld Nasso, Beth Sieloff, Cindy Cisneros, Ysabel Duron, and Benoit Blondeau for their input on this project. Thank you to the advisory board members as well as Lindsay Houff and Linda Bohannon for help with survey dissemination. Review of a prior draft by Larissa Nekhlyudov and Maureen Killackey is much appreciated.

References

- Tian Y, Qiu X, Wang C, et al. Cancer associates with risk and severe events of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:363-374.

- Lee LYW, Cazier JB, Starkey T, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1309-1316.

- Zhang H, Han H, He T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19–infected cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:371-380.

- Zarifkar P, Kamath A, Robinson C, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2021;33:e180-e191.

- Yang L, Chai P, Yu J, Fan X. Effects of cancer on patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 63,019 participants. Cancer Biol Med. 2021;18:298-307.

- Yousefi Afrashteh M, Masoumi S. Psychological well-being and death anxiety among breast cancer survivors during the Covid-19 pandemic: the mediating role of self-compassion. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:387.

- Leach CR, Kirkland EG, Masters M, et al. Cancer survivor worries about treatment disruption and detrimental health outcomes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39:347-365.

- Gallo O, Bruno C, Locatello LG, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:6297-6304.

- Bargon CA, Batenburg MCT, van Stam LE, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient-reported outcomes of breast cancer patients and survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;5:pkaa104.

- Dhada S, Stewart D, Cheema E, et al. Cancer services during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of patient’s and caregiver’s experiences. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:5875-5887.

- Pratt-Chapman M, Moses J, Arem H. Strategies for the identification and prevention of survey fraud: data analysis of a web-based survey. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7(3):e30730.

- Arem H, Moses J, Cisneros C, et al. Cancer provider and survivor experiences with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e452-e461.

- Penedo FJ, Cohen L, Bower J, Antoni MH. COVID-19: impact of the pandemic and HRQOL in cancer patients and survivors. www.phenxtoolkit.org/toolkit_content/PDF/UMiami_HRQoL.pdf. 2020.

- GW Cancer Center. Advancing Patient-Centered Cancer Survivorship Care Toolkit. https://cancercontroltap.smhs.gwu.edu/news/advancing-patient-centered-cancer-survivorship-care-toolkit. Accessed February 8, 2022.

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. QualityMetric Inc; 1998.

- Baffert KA, Darbas T, Lebrun-Ly V, et al. Quality of life of patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Vivo. 2021;35:663-670.

- Seven M, Bagcivan G, Pasalak SI, et al. Experiences of breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:6481-6493.

- Graves CE, Goyal N, Levin A, et al. Anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based survey of thyroid cancer survivors. Endocr Pract. 2022;28:405-413.

- Klaassen Z, Wallis CJD. Assessing patient risk from cancer and COVID-19: managing patient distress. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(5):243-246.

- Tabaczynski A, Bastas D, Whitehorn A, Trinh L. Changes in physical activity and associations with quality of life among a global sample of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Surviv. 2022:1-11.

- Faro JM, Mattocks KM, Nagawa CS, et al. Physical activity, mental health, and technology preferences to support cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7:e25317.

- Baddour K, Kudrick LD, Neopaney A, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on financial toxicity in cancer survivors. Head Neck. 2020;42:1332-1338.

- Kirtane K, Geiss C, Arredondo B, et al. “I have cancer during COVID; that’s a special category”: a qualitative study of head and neck cancer patient and provider experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:4337-4344.

- Wang S-Y, Hsu SH, Gross CP, et al. Association between time since cancer diagnosis and health-related quality of life: a population-level analysis. Value Health. 2016;19:631-638.

- Firkins J, Hansen L, Driessnack M, Dieckmann N. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:504-517.