Meredith Doherty, PhD1; Jessica Jacoby, MS1; Amy Copeland, MPH2; Christina Mangir, MS3; Rifeta Kajdic Hodzic4; Tamara J. Cadet, MPH, LICSW, PhD1

1School of Social Policy and Practice, University of Pennsylvania

2Small Spark Consulting, LLC

3Rhizome Consulting, LLC

4Association of Community Cancer Centers

Background: Cancer-related financial hardship is linked to poor health outcomes and early mortality. Oncology financial advocacy (OFA) aims to prevent cancer-related financial hardship in oncology settings by assessing patients’ needs and connecting them to available financial resources. Despite promising evidence, OFA remains underutilized.

Objectives: Describe oncology financial advocates’ perceptions about the challenges to and opportunities for implementing OFA in community cancer centers.

Methods: Nine virtual focus groups were conducted with 45 oncology financial advocates. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using template-based thematic analysis informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR); 2 study team members coded each transcript, and all 6 team members identified emergent themes.

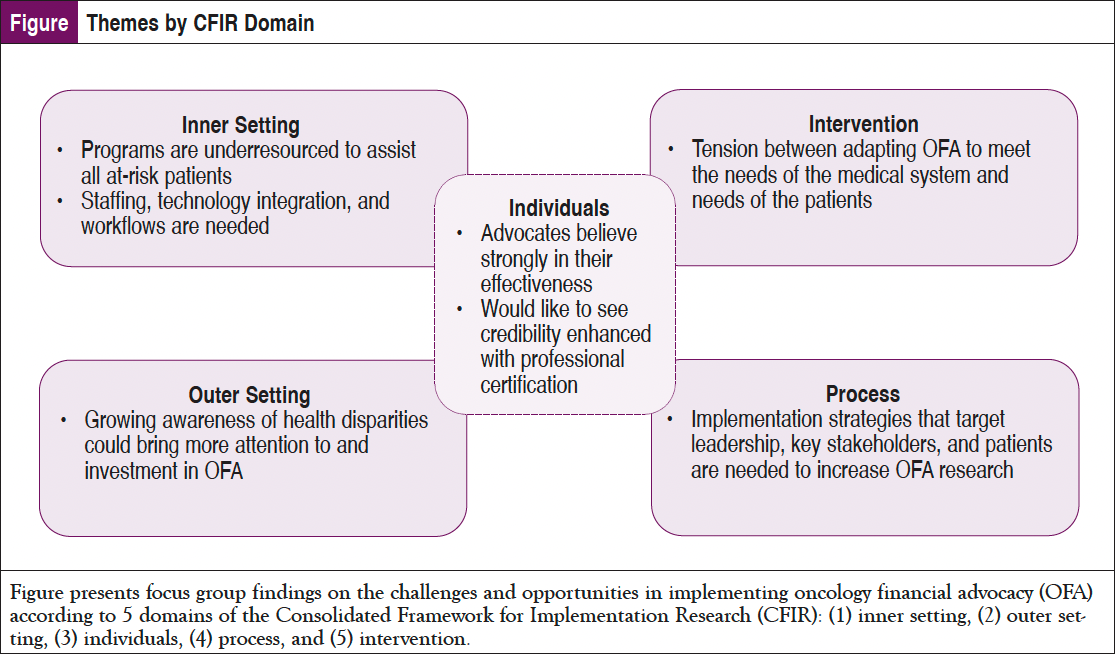

Results: Salient themes were identified across all 5 domains of the CFIR framework: (1) intervention characteristics: participants described challenges of adapting OFA to meet the needs of the medical system instead of the needs of the patients; (2) outer setting: growing awareness of health and cancer disparities could bring more attention to and investment in OFA; (3) inner setting: programs are underresourced to assist all at-risk patients; staffing, technology integration, and network/communication workflows are needed; (4) characteristics of individuals: advocates believe strongly in the effectiveness and would like to see their credibility enhanced with professional certification; and (5) process: implementation strategies that target the engagement of leadership, key stakeholders, and patients to increase program reach are needed.

Conclusions: OFA cannot reach all at-risk patients because of understaffing, poor communication between departments, and a lack of understanding OFA as an intervention among colleagues, key stakeholders, and patients. To reach full implementation, advocates need assistance in making the case for more resources, research on patient outcomes, professional certification, and the use of policy to incentivize financial advocacy as a standard of care in medicine.

Medical and technological innovation have improved rates of detection and survival in many common cancers.1 However, new oncology treatments and diagnostics often come at a significant financial cost to patients.2 Bankruptcy is high among cancer survivors.3 In addition to high out-of-pocket costs, cancer patients and caregivers may experience work interruptions and income losses.4 At least half of US cancer patients report experiencing financial hardship that ranges from increased financial worry to difficulty paying bills.5 Patients often find it difficult to cope with the complexities of insurance, billing, and accessing co-payment programs while receiving cancer treatment. This complexity and the fragmentation of the US healthcare system result in administrative burdens for patients and caregivers. Administrative burdens may include disputing denials from insurance companies, coordinating payments, scheduling and clinical record transfers across specialists, and shopping around for more affordable medications. Administrative burden has been associated with delays in accessing care.6-8 Cancer centers may have processes in place for assessing financial distress and providing financial assistance. However, the processes tend to be delivered inconsistently and may fail to reach the patients in a thorough and timely way.9-11 To help patients navigate the complexities of paying for care and prevent financial burden, empirical evidence suggests that the use of financial advocates or navigators is effective.12

Financial advocates help patients to understand and navigate the complexities of paying for treatment while helping them to access programs that can reduce the out-of-pocket costs of treatment.13 Oncology financial advocacy (OFA) programs vary widely, however. The core components of the OFA intervention include identifying patients who would benefit from advocacy; providing out-of-pocket cost estimates and helping patients to plan for these expenses; providing education to help patients understand and optimize their health insurance; and connecting patients to a range of financial and material supports to ensure access to care and bolster quality of life.14 OFA connects patients to cancer programs and community-based resources (eg, more affordable health insurance plans, co-payment assistance programs, financial assistance grants, and payment plans) while reducing bad debt for cancer programs. Further, patients who use financial advocates report greater satisfaction with care and less financial worry.15-19 Despite promising evidence, OFA fails to reach many of the patients who would benefit from it.9,10 To broaden the reach of OFA, there is a need to understand the challenges and opportunities in implementing OFA in a range of cancer treatment settings.

Focus groups with financial advocates were conducted to understand the challenges they face in delivering their services across a range of settings and the resources they need to reach more patients. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a well-established conceptual framework of implementation determinants, was used to organize the inquiry and categorize findings.20

Methods

Nine focus groups were conducted to understand the barriers that financial advocates face in delivering OFA in a range of cancer treatment settings and to gather their suggestions for improving implementation. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) Financial Advocacy Network to participate in a virtual summit of 3 sessions on issues facing financial advocates. All members of the Financial Advocacy Network of the ACCC were invited to a virtual Financial Advocacy Summit, through which the focus groups were coordinated. The network invited people to the summit by email and advertisements on the ACCC website. The target group reached by email consisted of 107 OFA stakeholders who had signed up for the network email list, many of whom had attended events in the past. The network provides interdisciplinary OFA training to a range of oncology stakeholders who represent a range of professions, including financial advocates, navigators, nurses, patient advocates, physicians, pharmacists, and representatives of community organizations. Emails directed recipients to an online registration link where they could register for any number of the 3 summit sessions. Twenty-four registered for all 3 sessions, 12 registered for 2 sessions, and 9 registered for 1 session. On the registration page participants consented to participating in focus groups that would be recorded for the purposes of research.

Instrument

The semistructured research guide focused on 3 main topics of concern to oncology financial advocates: Screening for Risk of Financial Distress, Defining the Scope of Financial Advocacy Services, and Amplifying the Role of Financial Advocacy in Health Equity.

Procedure

Virtual summits were held over 3 days in September 2021. After a preliminary introduction and discussion, attendees were divided into 3 breakout groups for focus groups facilitated by assigned leaders. The focus groups were recorded on Zoom videoconferencing software (Version 5.13.5) and transcribed by 2 researchers with the assistance of Otter.ai.21,22 A total of 9 focus groups were conducted with an average of 8 to 12 participants in each group.

Analysis

Although the interview guide was broadly developed to focus on distress screening, the scope of financial advocacy, and financial advocacy in health equity, the focus group conversations evolved to focus on OFA implementation challenges. With this in mind, focus group transcripts were analyzed using template analysis based on a priori themes from the CFIR framework, and themes were also allowed to emerge inductively.23 The entire research team participated in coding: 2 researchers were assigned to each focus group to generate preliminary codes, and then the entire group participated in discussions to calibrate coding and reach consensus on the coding of each transcript. Findings were then summarized by CFIR domain: (1) intervention characteristics (eg, issues related to OFA and how it is perceived as an intervention); (2) outer setting (eg, the system and policy level conditions that influence how OFA is implemented); (3) inner setting (eg, the characteristics of the institution/organization where OFA is being implemented); (4) characteristics of individuals (eg, attributes of individuals involved in implementing the intervention); and (5) process (eg, activities involved in implementation) (Figure).

Results

Participants included 45 financial advocates from a range of practice settings (21 integrated health systems; 11 community cancer centers; 2 nonprofit advocacy organizations; 3 academic medical centers; 8 represented other settings). Most participants identified their professional role as financial advocates or social workers, followed by nurses, and patient navigators. Twenty participants reported their roles as program directors, supervisors, or administrators, and 25 indicated that they were in direct practice. Participants reported barriers to implementing OFA and generated suggestions to improve care delivery.

Intervention Characteristics

Evidence Strength and Quality: Advocates were concerned that perceptions of OFA were too focused on the financial benefit to the cancer programs. Participants described how their interactions with patients were driven by a concern for the patient’s well-being, yet they acknowledged the competing demands and pressures to meet the cancer program’s “bottom line.” These competing incentives influenced how they delivered the intervention. The demonstrated value of OFA to cancer programs was a double-edged sword for advocates who believed that value arguments for implementation would increase buy-in among leadership, but they expressed concern about how it would shape the delivery of the intervention itself. Participants expressed that while both patient and cancer program needs can be met with a financial advocacy program, patient outcomes must be prioritized. Advocates said:

Everything that we do, in my opinion, should be patient centered. We should always put the patient first. Sometimes it gets tempting, when you do financial advocacy, that we focus our attention on how much we’re saving the hospital or the provider, and sometimes forget about the impact on the patient. And so central focus is about treating and healing the patient from a financial toxicity standpoint.

I think that a lot of times when you help the patient with co-pays and some of their financial concerns, you also can benefit the organization. I do believe, though that at the crux or the core that it has to be patient-centered and not provider or, you know, the clinic-centered.

You know, obviously there is a return on investment for the provider or the hospital system that does this and does it well. But there’s additional value here that’s very difficult to measure. You know, patient experience, patient stress level, access to care. It impacts so many different aspects and levels of the patient’s care, not just the financial. So, we probably should include or have a conversation about, what are all of the different values that this program would bring to a health system. And that might help get the attention of the stakeholders in the hospital systems that are looking at adding this.

Advocates described OFA as highly adaptable, meaning that it could be interpreted and delivered in many different ways. They felt that this feature was both a strength and a weakness.

Complexity: Participants described the complexity of healthcare payment systems, and that as a result OFA was necessarily a complex intervention. They discussed the complex nature of their work and the specialized knowledge required for it. They noted that ever-changing federal and state laws, regulations, policies, coverage requirements, assistance opportunities, and eligibility requirements added to the complexity. Participants acknowledged that many of the populations they served were uninsured or underinsured and had a range of unmet social needs, including needs for transportation assistance and help applying for public benefits. Advocates described how they built relationships with and earned the trust of patients who were not used to receiving help. They reasoned that their years of experience and time in the field improved their ability to build these relationships. Advocates said:

Just because a person has coverage doesn’t mean it’s gonna, you know, cover all the services that the physician is going to provide, understanding what a prior auth is, understanding what services are not uncovered, that means ultimately, it could be the patient’s responsibility and being able to educate the patients accordingly.

And if you’re constantly talking to that individual, and even bringing up some of those hard to talk about conversations, as you’re going along, they begin to trust you and relax and say, ‘Okay, I can trust this person, and it’s okay to talk to them.’ Because for the most part, I don’t deal with individuals that have insurance. So that’s even a more difficult conversation to have, because these are underserved individuals in the community. So they’re underserved in a lot of different ways in the community. And when they come into a healthcare institution, at first you’re saying to them, ‘How can I help you?’ ‘You want to help me? I don’t see this out in the community so what...what’s going on,’ right?

Adaptability: A common problem they described was being understaffed and underresourced to meet patient needs, which limited the number of patients that could be seen and forced them to ration services to the highest priority groups. Sites varied in how they determined which groups were the highest priority groups. Advocates described OFA as highly adaptable, meaning that it could be interpreted and delivered in many different ways. They felt that this feature was both a strength and a weakness. In standardizing the intervention, they suggested developing program guidelines to fit the needs of higher and lower resource environments; they discussed developing OFA guidelines with minimum and enhanced tiers so that cancer programs with fewer resources could implement less intensive (but still effective) adaptations of OFA. Advocates said:

One of the things I said, jokingly, is like, silver and gold plans, right? So this is silver advocacy program. This is a gold advocacy program, but more just to say, hey, it exists, but it exists to what level, you know what they’re able to, because we know each cancer center, depending on how big they are, if they even have this role, you know, you can’t expect them to do that full loop of a closure for each patient. So with that, it’s more understanding what are the core functions? We’d like a goal of understanding and standardizing across the board.

So we need to add to that conversation…what are the standards that need to be in place for the role itself? Understanding all of the different options that are out there to help navigate patients from avoiding financial toxicity, it gets complex pretty quickly. And so there should probably be a conversation about what are the minimum requirements that a financial advocate should be able to do, or to be able to function in this role?

Cost: Perceived costs of setting up an OFA program were noted as a barrier to implementation. However, the advocates highlighted that the intervention returns value to the cancer program by preempting patient payment problems. They emphasized that while calculating the anticipated costs and potential financial benefits of an OFA program is a practical step in the planning process, “bottom-line” reasoning cannot be the only motivation for building and sustaining an OFA program. One advocate said:

And when we reported it to that business office, ‘hey, the free drug program saved our cancer center a million dollars this last fiscal year,’ it didn’t mean much to them. The way that they looked at the infusion-free drug program was that, ‘is it really a savings if the insurance denied it?’ They didn’t see it from the care team point of view of, ‘this is needed for my patient’….So, I think the different stakeholders have a different value on how they feel about the advocacy program and what it brings.

Outer Setting

Patient Needs and Resources/Peer Pressure: Advocates expressed concern that inconsistent or absent financial and social need screening led cancer programs to underestimate the true extent of financial toxicity among their patients and minimize the need for skilled financial advocates. Participants noted, however, that cancer programs were becoming more aware of the prevalence of financial toxicity and its impact on cancer patients in general. The predominance of research, media coverage, and newly implemented screening tools for social needs and psychosocial distress have placed pressure on cancer programs to act, setting the stage for the implementation of OFA programs. One advocate said:

For me, I think it would be advantageous for us to focus on the [screening] tools, because that seems to be one of the glaring inefficiencies across the cancer programs – that there’s not one tool that we all can use to identify financial stress and financial toxicity. So if we could drill down on some key components to a tool that we all could use across the board, it would help us kind of measure how well we’re doing in that area where right now it’s kind of all over the place, we really don’t have anything to you know, identify what our patient’s needs are.

Cosmopolitanism: Advocates described their need to be in communication with other organizations to meet patients’ needs, especially patient grant and co-payment programs, to facilitate referrals and track when funds open and close. They discussed leveraging their relationships with representatives from pharmaceutical companies to advocate for more co-payment resources when they noted gaps in coverage. One advocate said:

We talked a lot about the education as well, to us and to our advocates, and how we’re doing it into the patients. I think something uniquely brought up was making sure that we have tools and resources for the patients as well, or partnering with the organizations who already have the tools and organizations to help the patients understand. You know, we do a lot of education internally with each other, or helping each other or to launch things.

External Policy and Incentives: Participants noted the lack of OFA in guidelines and regulations and felt that lack of interest from the government or other institutions that can influence the quality of cancer care delivery slowed the active proliferation of OFA as a standard of care. Participants acknowledged the growing interest in addressing social needs and the financial burden of care at the federal policy level, and they explored how some current policies could be augmented to incentivize patient navigation and advocacy programs. Participants noted that it would not be a “huge legislative leap” to include OFA in existing programs and policies. Existing government programs like Medicare and Medicaid could be expanded to regulate and include reimbursement for OFA. Advocates said:

I just wanted to jump in on the conversation here about having standards in place for oncology programs, who have financial advocacy. One, once again, I’m going to say 100% agree with this. It’s actually kind of shocking, to understand that when it comes to financial advocacy, technically, there’s no state regulations, federal regulations for people to be in this role.

I think every time that you work with a body, such as the Commission on Cancer and the American College of Surgeons, which really does have the majority of cancer programs, or cancer patients in the program, we need to lobby as a group to implement a standard related to financial advocacy….So, I think as a group, we need to lobby for that.

Inner Setting

Structural Characteristics/Networks and Communication: Participants noted that large institutions and siloed departments (eg, surgical vs radiation vs pharmacy and medical oncology; clinical vs financial) made it difficult to refer patients for OFA and for advocates to get accurate cost estimates to patients. Advocates stated that access to integrated, real-time information on patients’ treatment and associated costs (eg, integrated electronic health record) would make it easier to deliver care. They also noted that care providers across the system needed to learn about OFA services at their institution and know how to refer patients to them. Advocates said:

…the sky’s the limit on the automation, it would be great if we get some kind of notification that there are new consults. And then are there denials? Did they lose their insurance? Did they...what is their...what is their current balance right now where you can maybe set a threshold where you get notified if they have more than $500 in outstanding balances that would be or whatever, you know, baseline you want to set so a lot of more...a lot of times as we know we kind of stumble across ‘Oh, there’s a denial, Oh, you have no more or your insurance coverage is not valid anymore and patient access did not notify us.’

These are silos. Even though we have an EMR [electronic medical record] and tumor boards, and notes, and a lot of communication amongst our treatment teams – a patient will go to one appointment and hear about a cost for that appointment. They might have had an inpatient stay and they have a bill from that. They go to physical therapy and they have a co-pay there, then they have their cancer treatment – and that’s a silo.

It takes a village to accurately assess [a patient’s financial needs]. Sometimes patients share more with others based on their relationship. [So] We use our financial coordinators, navigators, social workers, and others to ask questions throughout the cancer journey to ensure we meet their needs as those financial needs change often.

Advocates described how they learned and honed their skills on the job, and that this created a long learning curve for new hires and fostered idiosyncrasies across programs.

Tension for Change: Advocates described bringing patient stories and aggregate data on patient need to the attention of leaders to highlight the need for change. They encouraged advocates to use their experiences and the stories patients have told them to drive change from the leaders of medical institutions. One advocate said:

I think having the patients voice concerns loud enough actually makes the stakeholders listen a little bit too. I don’t know if any of you are...use, like, the Press Ganey survey, but we repetitively...we constantly got feedback from our patients that they felt like you know, the care, their cancer care was amazing, clinically, but the whole billing cycle financial part of it was a nightmare for them, and trying to deal with that on top of the cancer diagnosis was just too much. So I started to compile that information from our Press Ganey, you know, and it kind of gave me a little bit more leverage in my discussion with the cancer team leadership.

Available Resources: Participants described needing more resources for their programs; staffing, physical space, and time were all barriers to delivering what they perceived to be effective care. Due to understaffing, they needed to ration their time with patients (eg, no follow-ups) or prioritize only patients with the highest need. They also noted that advocates should be aware of available resources (within the cancer program and wider community) and have methods for addressing identified needs before widespread financial and social needs screenings are implemented. One advocate said:

Face it from a staffing perspective, you know, every program doesn’t have the number of patient advocates to talk to every patient that may come through their door. So you try to, you know, streamline it and really try to drill down on the ones that actually have the need, but that, you know, it’s kind of arbitrary.

Characteristics of Individuals

Knowledge and Beliefs About the Intervention: Participants felt that other providers (eg, physicians, nurses) were not always aware of OFA or were not comfortable making referrals to them. They believed that if their cancer program colleagues understood the full scope of what advocates do, and that the intervention aims to protect patients, they would feel more confident coordinating patient care with advocates. Advocates said:

…then all of our providers, all the clinic staff, would know that if the patient says anything about a concern about insurance or bills, or costs of something to reach out to the financial counselor.

I think ultimately, the importance of financial advocacy in each cancer program would be a good place to start. I know there are some smaller organizations that do not have the role. And I think defining what advocacy...advocacy is within a cancer organization. Because we have, you know, there’s social workers that serve as advocates, there’s financial counselors that serve as advocates.

Self-efficacy: Advocates described how they learned and honed their skills on the job, and that this created a long learning curve for new hires and fostered idiosyncrasies across programs. Advocates felt strongly about the need for a certification program that would standardize preparation and lend credibility to the profession. Advocates said:

…thinking about some of those financial problems and barriers that can happen along the way. You know, you kind of learn how, after dealing with so many patients over the years, what are some of those things that you really need to address.

The patient’s looking at us as a resource for everything…who’s going to bill those foundations? Who’s going to get the patient their claims? Who can I send that patient to get them that surgery estimate?

I not only help with bills and costs but also with obtaining food, housing, and utility payment assistance, so I tend to be needed all over the place.

What are the core functions that a cancer center – regardless of how big they are, how many advocates they have – could do? Of course, helping the patient understand, understanding the patient’s actual coverage, optimizing resources, and you know, then getting into health literacy…of course, what everyone always wants [is] some type of certification. That’s definitely a goal, I think across the board is something that says ‘I’m certified as an oncology financial advocate.’

Process

Engaging Patients: Advocates focused on the challenges of engaging patients who were cautious about interacting with a financial advocate. Patients expected to hear from a financial counselor about unpaid balances and did not expect a financial advocate to be on their side. They talked about the importance of building trust and described some of the strategies they used to differentiate themselves from billing department representatives. It took time to build a relationship in which patients believed they were actually there to help them. Additionally, they suspect that patients had fears about being abandoned by their providers if they revealed payment issues. Some patients needed repeated contact to build trust and open up about their concerns. Advocates said:

I joke, I point to my right shoulder or my left shoulder and I tell them I have an invisible sign that says I’m not a bill collector. And it’s like it’s a good leeway into the patient’s realizing that we’re there not to just say hey, you have great insurance or you have crappy insurance, that we’re truly part of their support team.

…‘Okay, if somebody from finances coming to knock on my door, they want money.’ So to me, the way I start my introduction to the patient is, ‘I’m here to help you – to help you navigate, and I’m here to save you money versus taking money from you.’ So kind of an introduction, in a nutshell, is helping set the tone.

Engaging Stakeholders and Champions: Many of the advocates saw themselves as internal champions of the practice but needed their voice to be bolstered by nurses and physicians, because they lacked the power needed to lead systemic change. Participants focused on 2 strategies for engaging stakeholders in building OFA: (1) making the business case for OFA as a high-value intervention, and (2) using patient stories and data to demonstrate the need for OFA.

They also felt certification and policy change would give them more power to advocate for their patients. One advocate said:

I think it’s almost overwhelming to think of creating a financial advocacy for a large health system. But having...so in the health system that I work in, we have a new vice president, and he has been part of it longer than our health system has. And when he came in, he met with all of us, and he asked what did each of us want? And I said financial advocacy. And he said, ‘it’s at the top of my list.’ So he was the driving force to getting this done, even though it was something that we had been addressing for a few years.

Discussion

In this study, financial advocates were asked directly what they believed the barriers to OFA implementation were, and what they needed to effectively implement OFA so that more cancer patients can benefit from their services. The business case for OFA has been disseminated widely, with evidence that the intervention reduces lost revenue and bad debt for cancer programs.15 As a result, advocates experienced a tension between delivering patient-centered care and cancer program–centered care. They felt strongly that the relationship between advocate and patient is key to OFA effectiveness. Participants reported that their OFA programs were understaffed and underresourced to meet the needs of all patients. They noted that poor information sharing and communication between clinical and financial departments (as well as other siloed departments) of the cancer program led to inefficient delivery of OFA. One might infer that institutional investment in OFA programs could too easily use economic value as the primary metric for success and minimize investment to the point where only the bottom line is optimized, potentially leaving patients without adequate support.

Participants expressed excitement for what they perceived to be a window of opportunity for OFA. The current social climate has drawn attention to the financial burden of cancer and its implications for health equity. They described an urgency to use the current climate to advance the dissemination and implementation of patient-centered and equity-focused models of OFA. By framing OFA as an intervention that can address health equity, they felt the intervention had a chance of growing and helping more patients who need it. Advocates discussed the importance of engaging leaders and shared strategies for engaging patients, many of whom may be apprehensive to work with them due to the stigma of financial problems and fear of losing access to treatment.

Because the landscape of healthcare financing is so complex, financial advocates have a rich and specialized set of skills and knowledge that could be standardized. Advocates felt strongly about the need to enhance their credibility, professionalization, and job preparation through a certification program. Certification could provide the confidence and credibility to advocate for their patients’ needs and apply appropriate interventions.

Bankruptcy and other financial toxicities, like anxiety, depression, poverty exposure, and cost-related nonadherence to treatment, are real consequences of the cost of cancer treatment for many cancer patients.4 The cost of care and the complexities of the US payment system are barriers to care for many patients.6 Cancer-related financial hardship (ie, financial toxicity) has been associated with a host of adverse health effects, including early mortality.4,24 Although assertive structural interventions are needed to address the root causes of medical financial hardship, OFA as a clinical intervention has been shown to improve patient access to financial assistance, improve patient satisfaction and quality of life, and reduce financial worry.14,16,19 The number of studies examining the effectiveness of OFA interventions is growing, and experts now recommend OFA to prevent and reduce financial toxicity at the direct practice level.25,26

By applying an implementation science lens, CFIR, our findings contribute to the extant literature on OFA. Multiple studies have shown that the primary barrier to integrating OFA into routine care is that programs are underresourced to meet patient needs.9-11 Advocacy programs need greater investment in staffing, workforce development, and technology that supports real-time information transfer across departments. Our findings suggest that advocates have been able to build buy-in among leadership and increase investment for their programs by: (1) generating compelling program reports that combine data on patient needs and outcomes with cost–benefit data for the cancer program, and (2) finding other clinicians (eg, physicians, pharmacists) to champion their programs. To achieve these objectives, advocates should be collecting data on their services consistently and create opportunities to spread the word about their services across the cancer center.

In conclusion, although more robust structural interventions are necessary, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness and value of OFA. This study contributes to the emerging literature on the implementation of OFA and suggests that, with greater investment and standardization, OFA could become standard of care available to all patients.

Disclosures: The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

Funding: (TC)-K23AG062795

You Might Also Like

References

- Zeng C, Wen W, Morgans AK, et al. Disparities by race, age, and sex in the improvement of survival for major cancers: results from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program in the United States, 1990 to 2010. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:88-96.

- Keehan SP, Cuckler GA, Poisal JA, et al. National health expenditure projections, 2019-28: expected rebound in prices drives rising spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:704-714.

- Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1143-1152.

- Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: what do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2018;27:1389-1397.

- Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can’t pay the co-pay. Patient. 2017;10:295-309.

- Doherty M, Thom B, Gardner D. Administrative burden associated with cost-related delays in care in U.S. cancer patients. https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-1895068/v1/2b616014-08b1-4d42-8729-65b39c5db200.pdf?c=1684259069. August 19, 2022.

- Kyle MA, Frakt AB. Patient administrative burden in the US health care system. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:755-765.

- Herd P, Moynihan D. How administrative burdens can harm health. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20200904.405159/#:~:text=Administrative%20burdens%20can%20negatively%20affect,come%20from%20navigating%20burdensome%20bureaucracies. October 2, 2020.

- Biddell CB, Spees LP, Petermann V, et al. Financial assistance processes and mechanisms in rural and nonrural oncology care settings. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e1392-e1406.

- de Moor JS, Mollica M, Sampson A, et al. Delivery of financial navigation services within National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:pkab033.

- Khera N, Sugalski J, Krause D, et al. Current practices for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN member institutions. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18:825-831.

- Edward J, Petermann VM, Eberth JM, et al. Interventions to address cancer-related financial toxicity: recommendations from the field. J Rural Health. 2022;38:817-826.

- Sherman D. Oncology financial navigators: integral members of the multidisciplinary cancer care team. Oncol Issues. 2014;29(5):19-24.

- Doherty MJ, Thom B, Gany F. Evidence of the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of oncology financial navigation: a scoping review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2021;30:1778-1784.

- Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, et al. Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient out-of-pocket spending. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(suppl):S74-S79.

- Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122-e129.

- Wheeler S, Rodrigues-O’Donnell J, Rogers C, et al. Reducing cancer-related financial toxicity through financial navigation: results from a pilot intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29. Abstract 694.

- Lambert C, Legleitner S, LaRaia K. Technology unlocks untapped potential in a financial navigation program. Oncol Issues. 2019;34(1):38-45.

- Knight TG, Aguiar M, Robinson M, et al. Financial toxicity intervention improves outcomes in patients with hematologic malignancy. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e1494-e1504.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

- Otter.ai. Voice meeting notes & real-time transcription. https://otter.ai/. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Zoom Video Communications. One platform to connect. https://zoom.us/. Accessed February 4, 2023.

- Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Doing Qualitative Research. Research methods for primary care. Vol 3. Sage Publications, Inc; 1992:93-109.

- Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34:980-986.

- Lentz R, Benson AB III, Kircher S. Financial toxicity in cancer care: prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:85-92.

- Knight TG. Interventions for financial toxicity: more crucial than ever in the time of COVID-19. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:915-916.