Linda Fleisher, PhD, MPH1; Cassidy Kenny, MBA1; Emily Gentry, BSN, RN, HON-ONN-CG, OCN2

1Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA

2Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators, Cranbury, NJ

Background: The CAPE Lung initiative is a web-based patient education platform created by the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+); it is designed to improve patient education and enhance patient care. CAPE permits navigators and cancer care teams to send patients “e-prescriptions” that contain personalized education customized for each patient’s circumstances and treatment status.

Objectives: Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) in collaboration with AONN+ conducted a pilot study to evaluate patient efficacy, provider feedback, and implementation of CAPE Lung using an implementation science framework in diverse cancer settings.

Methods: Patients were recruited to the evaluation at each site and completed a baseline survey, received personalized e-prescriptions, and completed a 1-month follow-up survey over the phone with the FCCC research team about their experience with CAPE. Implementation strategies were site specific and tailored to meet the needs of each site’s clinical workflows. The perceived usefulness and educational value of the CAPE platform across the diverse sites were measured through meeting notes, debrief interviews with site staff, and a focus group with navigators beyond the pilot sites.

Results: Fifty-three English-speaking patients with non–small cell lung cancer were enrolled in the CAPE program within 12 weeks of their diagnosis. The majority of the patients who used the CAPE resources viewed it positively. However, some patients felt overwhelmed by their diagnosis or other external factors. In reviewing the implementation data, several factors were identified that influenced the potential effectiveness of CAPE, such as overwhelmed patients, short-staffing, low technology literacy, and provider handoffs throughout the trajectory of care.

Conclusion: Overall, patients and providers felt that CAPE is a supportive resource, that it fit within patient workflow practices and matched patient educational needs. Based on these findings, AONN+ believes there are strategic points in the patient care process at which CAPE could be introduced into the treatment trajectory. A one-size-fits-all approach to implementation timing may not be optimal, and the insights from these preliminary findings will guide future implementation and dissemination of CAPE.

When diagnosed with cancer, a patient and their family’s quality of life (QOL) is often impacted immediately and includes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects. To address QOL with high-quality care, it is essential to have extensive patient education covering the entire disease trajectory. It has been shown that especially at the time of diagnosis, patients and their caregivers often feel that they have not received all-encompassing information, and their needs have not been met concerning information about their diagnosis and treatment.1,2 It is critical that patients and caregivers are included in all aspects of their cancer care by acknowledging their perceived QOL, understanding their goals related to care, and confirming their preferences.3-5

Moreover, ensuring that patients receive the “right” information at the “right time” addresses information overload that can be overwhelming in cancer treatment. Just-in-time, web-enabled digital health patient education tools designed to streamline and personalize patient education have shown great promise, yet implementing these innovations into practice remains challenging from both a patient and provider perspective.6-8 Digital health education materials, such as web-based interventions and mobile/online health tools, have become increasingly utilized in patient care and healthcare education as people of all ages regardless of demographic backgrounds are using digital modalities of communication more frequently. The use of digital health facilitates patient education by optimizing the frequency and timeliness of healthcare education interventions and allows for education to be personalized and in sync with patient and caregiver needs.8-10 The goal of digital health interventions is to supplement learning outcomes and promote informed decision-making in patients through shared information, knowledge, and support regardless of geographic distance or resources within diverse clinical settings.8,10

Although digital health education materials and technology continue to evolve and have shown promise, real-world application of these technologies remains low. To implement digital health tools in real-world clinical settings, implementation must be tailored to meet the needs of each institution’s patient population and clinical workflow. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.11,12 Research into the dissemination and implementation of digital health interventions has increased rapidly in recent years. The rise of research into evidence-based interventions, practices, and policies in real-world clinical settings has optimized the safety and effectiveness of digital health, with researchers not only looking at how to implement these interventions but also why they may or may not work across populations and health systems. In addition, the introduction of these tools by a trusted source, such as oncology navigators, may encourage utilization of digital health tools in diverse clinical settings.11

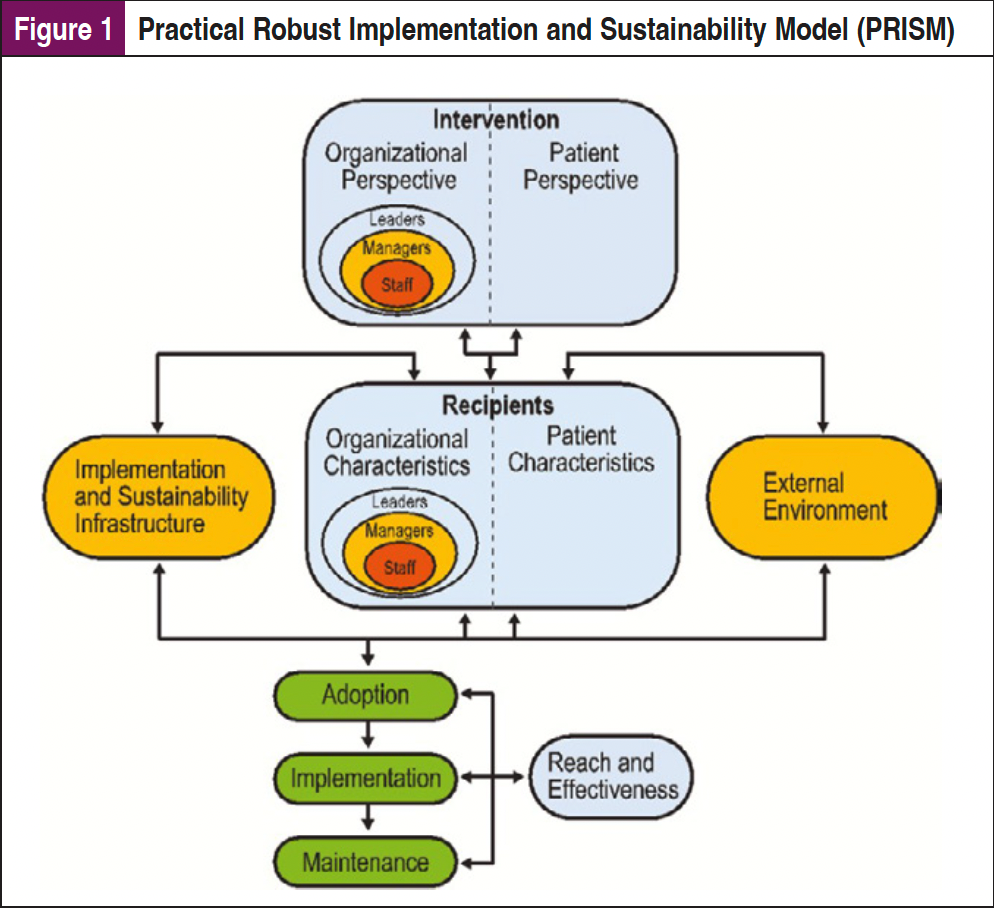

These types of tools can be implemented to benefit both the patient and the provider in terms of efficacy, accessibility, and feasibility. However, implementation of digital health tools into clinical care requires planning and an understanding of the institutional context and workflows to ensure that these tools are truly integrated into care. Dissemination and Implementation (D&I) science frameworks are essential to a systematic approach to explore the factors that will facilitate implementation of these tools. There are multiple D&I frameworks that can be considered, including the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM), which expands the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to identify contextual factors (eg, organizational and patient perspectives) impacting implementation (Figure 1). These multilevel contextual factors can impact operational processes and available resources unique to different healthcare sites and systems.13-15

Cancer Advocacy & Patient Education

To address patient education gaps throughout the cancer care trajectory, the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) developed the Cancer Advocacy & Patient Education (CAPE) Program, a digital education platform that provides a multimedia approach to patient education by providing an extensive library of content from respected organizations that is personalized by navigators (and other health professionals) and delivered to patients through an easy-to-use online interface. The information within CAPE was curated through an extensive process with respected patient education and advocacy organizations and selected utilizing best-practice, evidence-informed resources.16

AONN+ partnered with Takeda Oncology and a multistakeholder coalition of leading patient advocacy organizations for lung cancer. A predetermined QOL model based on the domains of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being was utilized to determine the needs of patients and their caregivers. A comprehensive search of the published literature from the past 10 years was conducted. A total of 1610 articles were screened, 205 full-text publications were reviewed, and 50 relevant articles were identified. Findings from the review and analysis of relevant articles, using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) model, identified common areas of need/concern for patients with lung cancer and their caregivers.17

With the help of an integrated educational program such as CAPE, there is opportunity to actively engage patients and caregivers by assigning them materials relevant to their diagnosis, increase productivity, and allow them to become more involved in their treatment decisions and trajectory, ultimately increasing their QOL.

CAPE is designed to facilitate patient education by having navigators and healthcare professionals send personalized education to patients to engage, inform, and empower them throughout the trajectory of their care. The goal is to cultivate informed decision-making and improve QOL of their patients by utilizing the tool before/during/after patient encounters through an easily accessible platform that serves as a “one-stop-shop.” Through the use of CAPE, navigators and healthcare professionals are able to send personalized digital prescriptions from the online repository within the CAPE platform directly to patient and caregiver email addresses in real time from any device that connects to the internet. The resources within the CAPE platform can also be printed and viewed during patient encounters. Currently, the CAPE Lung platform has 7 modules, including understanding your diagnosis, treatment options, self-care, coping, shared decision-making, financials, and caregiver and family roles. Each module is carefully designed to support patients throughout the trajectory of their cancer journey, leveraging and carefully vetting reputable educational sites and resources commonly used within clinical settings by navigators and other healthcare professionals.

CAPE Lung Pilot Study

The CAPE Lung pilot study, conducted by Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC), focuses on the implementation of CAPE Lung in real-world settings and provides insights from both the perspective of navigators and patients.18 The evaluation provided an opportunity to gather patient feedback about how the CAPE platform improves understanding of their diagnosis, treatment, and coping abilities, as well as how they used this information in their discussions with providers. Additionally, the CAPE pilot study evaluated implementation in diverse clinical workflows and cancer centers. These insights and findings will guide future efforts to introduce the CAPE platform in a broad array of oncology care and broadly disseminate the findings to guide digital health intervention implementation in oncology care.

Objectives

The primary objectives of the CAPE Lung pilot were: (1) to explore patient perceptions about the value and impact of the CAPE platform to improve their self-efficacy in communicating with their physician regarding their lung cancer diagnosis, and (2) to evaluate the implementation barriers and facilitators to the utilization and sustainability of the CAPE platform in diverse oncology settings. Our evaluation focused on the barriers to implementation since we anticipated challenges in introducing patient education into clinical workflows.

Methods/Study Design

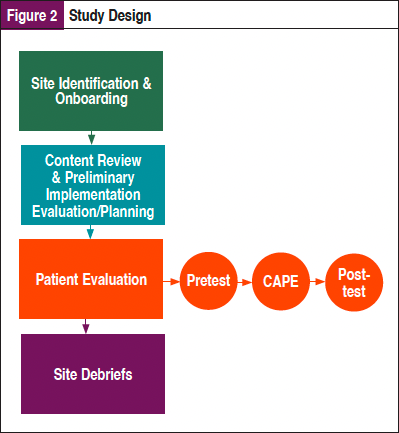

As shown in Figure 2, this multisite evaluation study employed a mixed-methods approach utilizing both qualitative and quantitative data to explore the perceptions and utilization of this comprehensive patient education platform on newly diagnosed patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and providers and explored the implementation of the tool in diverse clinical settings. In addition, the study team conducted extensive content review and implementation planning prior to the launch of the pilot.

Patient-Level Evaluation

A pretest/posttest design was utilized for the patient evaluation using standardized questions regarding knowledge, engagement with provider, and satisfaction collected through a baseline survey and telephone follow-up survey.

HIPAA-certified research staff and clinical teams at each site identified newly diagnosed patients with NSCLC at their first clinical visit and gave them more information about the CAPE study. Interested patients were verbally consented and verbally administered a short 5- to 10-minute baseline survey and then sent/printed an e-prescription for them to review at their earliest convenience. All sites were given a REDCap link specific to their site where they recorded all study-related data. Within REDCap, the study team captured patient contact information, consent status, and baseline responses.

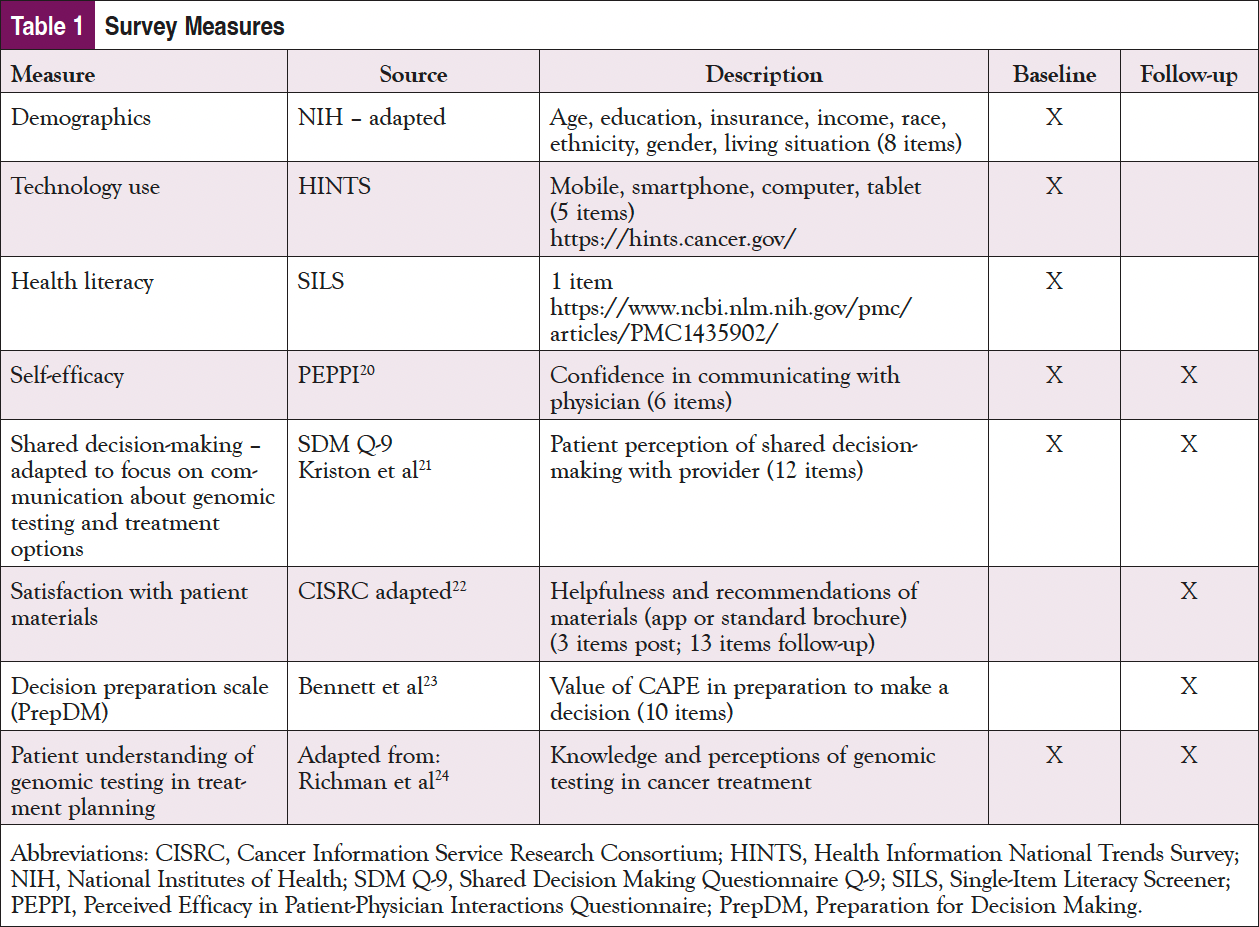

The FCCC study team conducted follow-up surveys for all sites and study participants over the phone 1 month after e-prescriptions were sent. The baseline and follow-up surveys for patients included common measures for technology use, including the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions (PEPPI), knowledge of genomic testing, Preparation for Decision Making (PrepDM), and satisfaction with the tool. In addition, the follow-up included multiple open-ended questions to gather feedback on the tool. The measures used are listed in Table 1.19-25

Implementation Site Identification, Onboarding, and Data Collection

Participating sites were identified by FCCC and the AONN+ team based on carefully defined eligibility criteria to ensure representation of various clinical settings, appropriate caseloads for study accrual, workflows, and navigation models to elicit insights from diverse provider and patient populations.

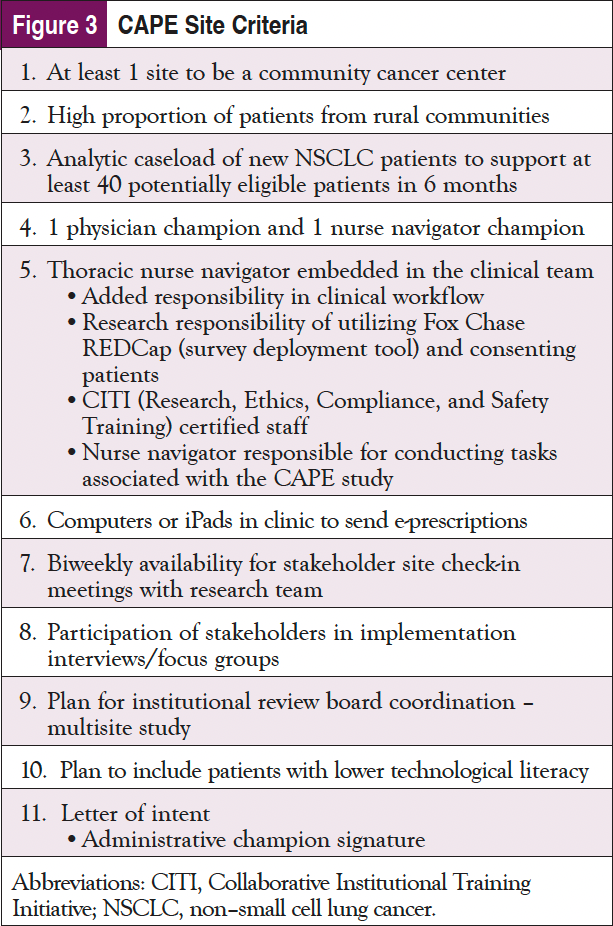

FCCC and Temple Fox Chase (TFC), both within the broader Temple University Health System, were the first sites identified and represented an urban/suburban health system that serves a diverse group of patients. Both FCCC and TFC had analytic caseloads large enough to support the needs of the CAPE study and different navigation models, as well as institutional support and buy-in. At TFC, there was no involvement of navigation but rather provider support, whereas at FCCC, they predominantly have intake navigators who touch the patients mainly when they are newly diagnosed. The additional sites were selected based on criteria shown in Figure 3 to ensure representation and commitment to the CAPE study.

Baptist Health Deaconess Madisonville in Kentucky and Vidant Medical Center in North Carolina were selected as additional sites in this multisite study. Both represent community cancer centers serving more rural populations. The Fox Chase team conducted training with the study teams at each site and completed regulatory responsibilities to onboard participating sites, including multisite institutional review board approval, contracting, and the Memorandum of Understanding.

Implementation at Pilot Sites

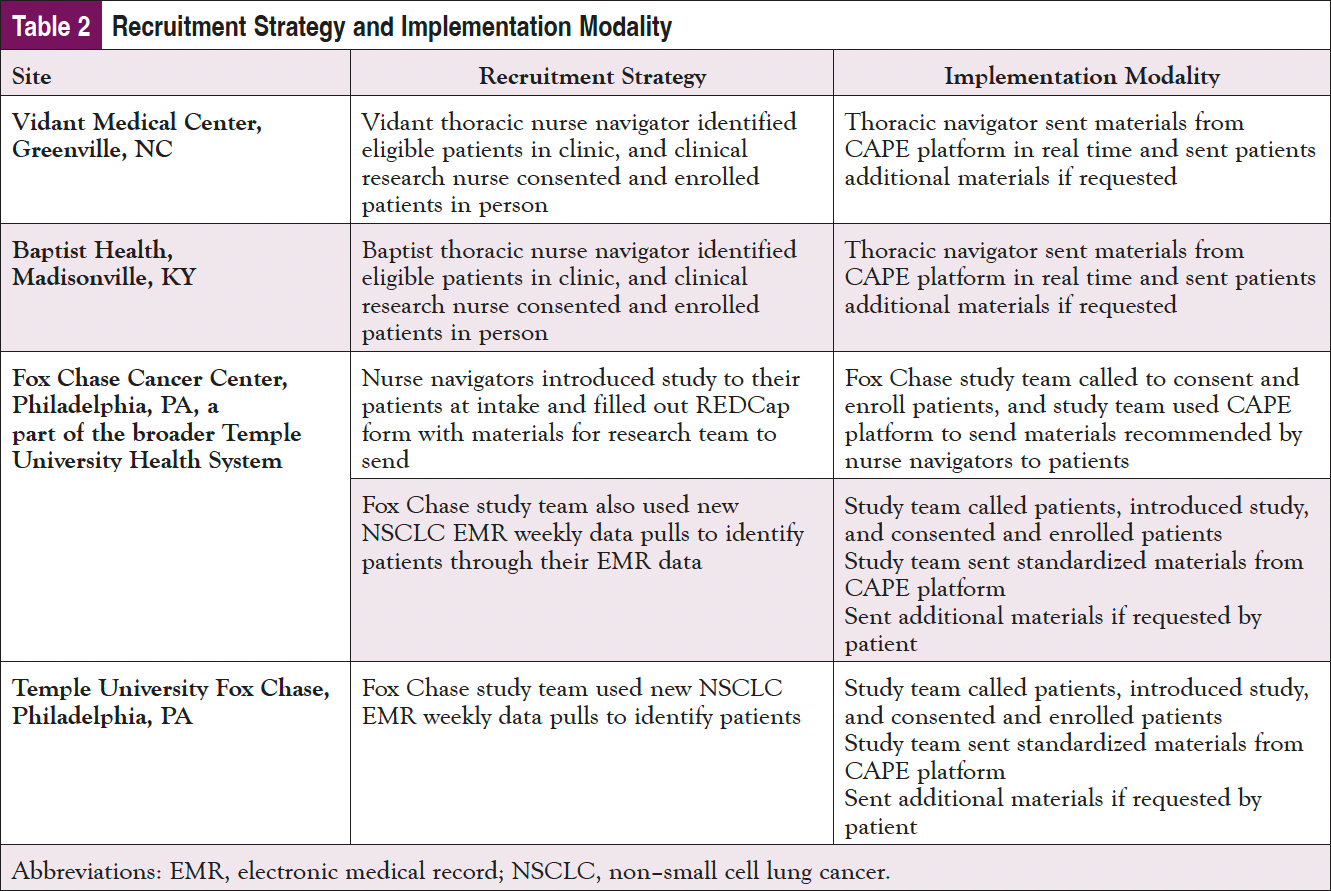

Patient recruitment and implementation of the study participants were tailored based on the needs, staffing, and resources at each of the 4 sites (Table 2).

It was recognized that each site would need to tailor their implementation based on staffing, clinical workflows, and patient populations. The data collection for implementation was predominately qualitative, including meeting notes (both before and during implementation), accrual review, and debriefing conversations.

Results

Patient Perspectives

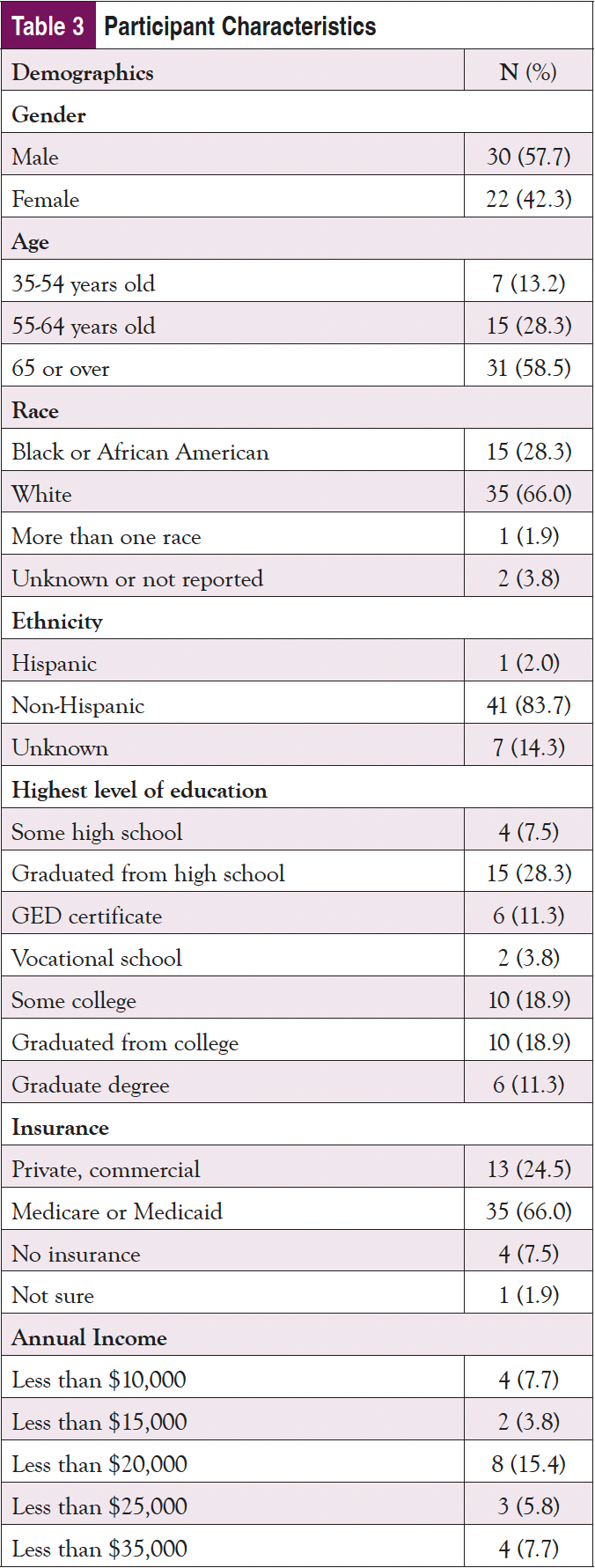

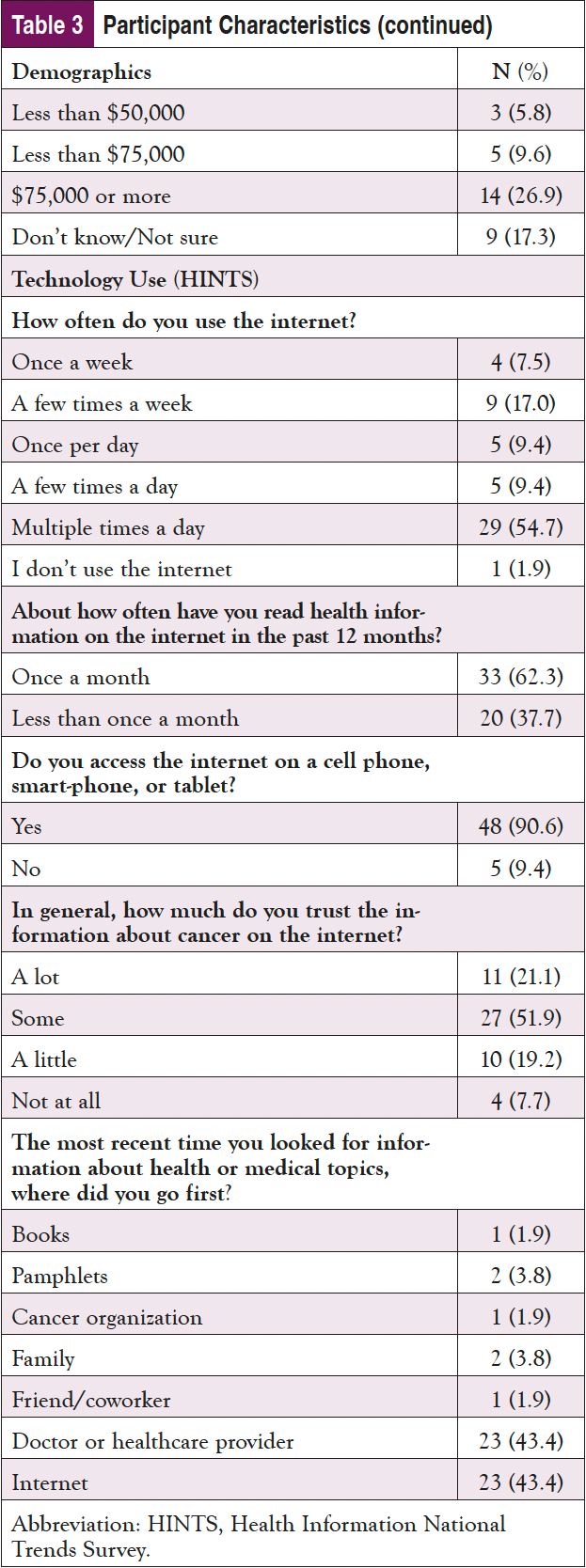

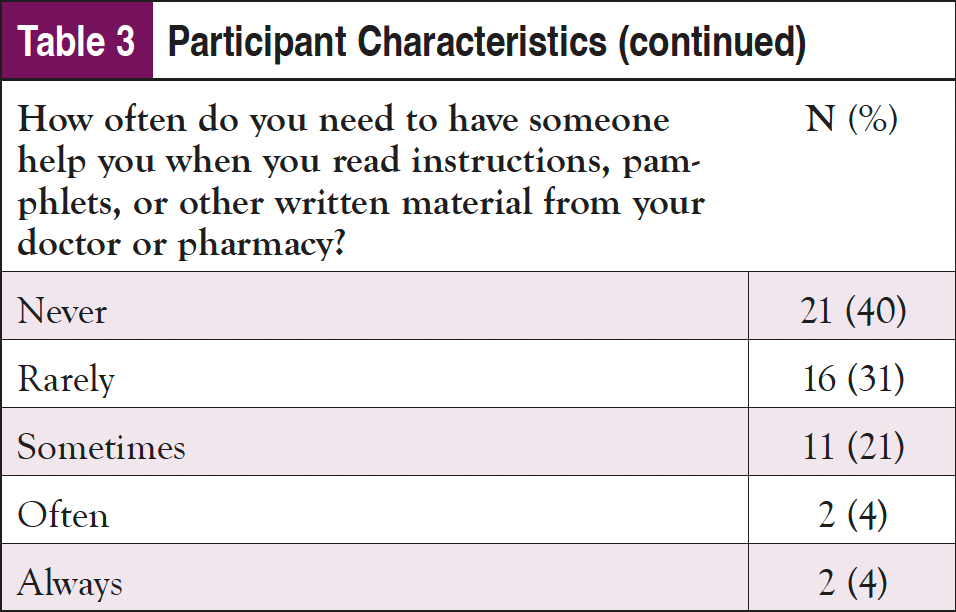

As shown in Table 3, nearly 60% of the sample identified as male and 65 years or older; almost 30% identified as Black or African American, and 2% indicated they were Hispanic. Only about one-fourth had a college education, and most were on federally funded insurance. Despite being an older population, nearly 3 in 4 participants indicated that they use the internet at least once per day, with over 60% using it multiple times per day; 90% of participants said that they access the internet using a cellphone, smartphone, or tablet. Fewer than half reported that the internet is their first source of healthcare information; however, only about 20% of the sample stated they trusted information about cancer on the internet “a lot." Doctors or other healthcare providers were the first source for an additional 40% of participants. Almost 1 in 4 participants indicated some issues with health literacy and reported sometimes needing help, and 4% reported they often or always need help when they read instructions, pamphlets, or other written material from their doctor or pharmacy.

On the posttest, participants were asked if they remembered receiving the CAPE email from their care team; 83% reported that they remembered. Of those, 1 participant received printed information, and the rest received information from CAPE via email. Over half (57%) of those sent materials electronically from CAPE reported that they opened the links. Of those who opened the links, most reported reading over the materials, and 2 reported printing the materials to review them further later on. While some could not remember whether they had opened any of the links, those who did recall opening the links reported that the information made them feel depressed, scared, or overwhelmed, and they were not interested in viewing them.

Self-efficacy and knowledge about genomic testing were compared between baseline and 1-month follow-up. To assess perceived self-efficacy, the shortened PEPPI scores were calculated. The PEPPI measure asks questions about a person’s confidence in getting a doctor to listen to their concerns rated on a scale of 1 (least) to 5 (most). The top score for the shortened PEPPI is 25. We asked an additional PEPPI question not contained in the 5-item set, “(Confidence) In your ability to ask a doctor for more information if you don’t understand what he or she said?” This question was assessed separately and had a top score of 5. PEPPI scores for both the shortened measure and additional question increased slightly in the posttest, indicating the patient materials may have been helpful in increasing self-efficacy.

Knowledge about genomic testing was assessed using an adapted knowledge test. In the pretest, participants were asked to first rate their knowledge on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) on the role of genomic testing in determining treatment options, followed by 5 knowledge questions, each worth 1 point for a total top score of 5. The same 5 knowledge questions were asked again at the posttest. The mean score for the self-assessment of knowledge was the same as the pretest knowledge scores, indicating that participants accurately estimated their knowledge regarding genomic testing. The posttest knowledge scores increased slightly, indicating that the patient materials were somewhat helpful at increasing knowledge.

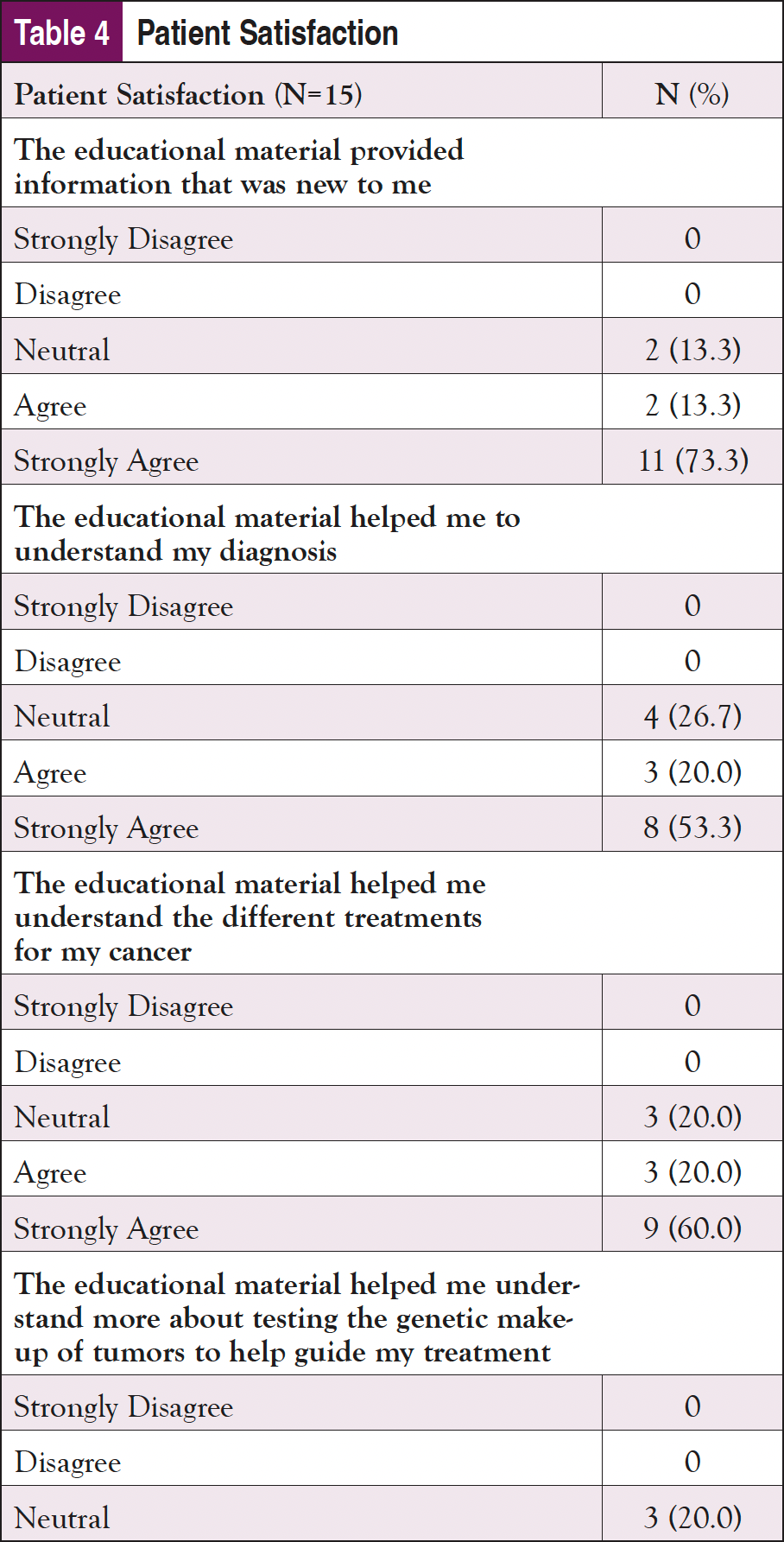

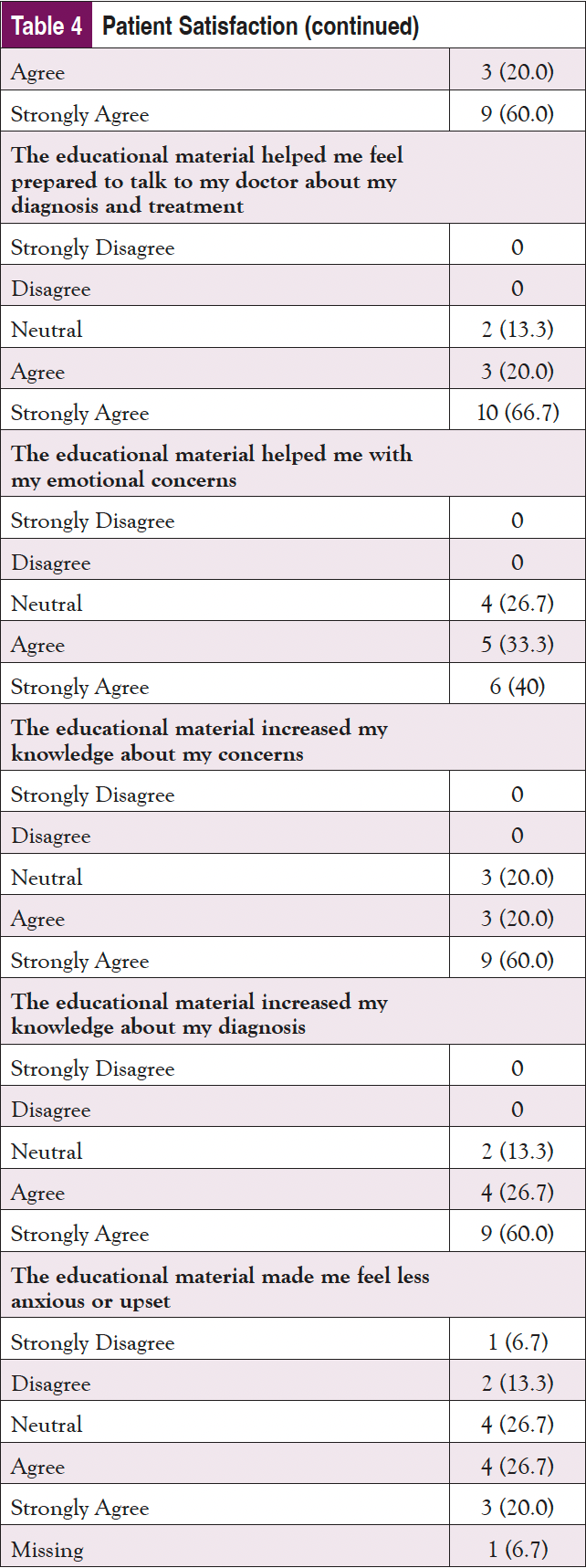

Finally, patient satisfaction with the materials and how prepared they felt to make a decision after using them were assessed (Table 4). In response to the satisfaction questions (rated from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”), the participants were highly satisfied with the materials. “Strongly Agree” was the answer most often selected for almost all of the satisfaction questions, although participants did not feel as strongly that the materials helped them feel prepared emotionally. In a question about whether the materials made them feel less upset, 2 Vidant participants selected “Strongly Disagree” and “Disagree,” indicating that they found the materials to be upsetting, or that they did not help in reducing anxiety. In terms of preparedness to make a decision, all participants were satisfied with how the materials helped to prepare them. “Somewhat Prepared” was the lowest response received on all of the questions, with the majority of responses being “Quite a Bit” or “A Great Deal.”

Organizational Perspectives

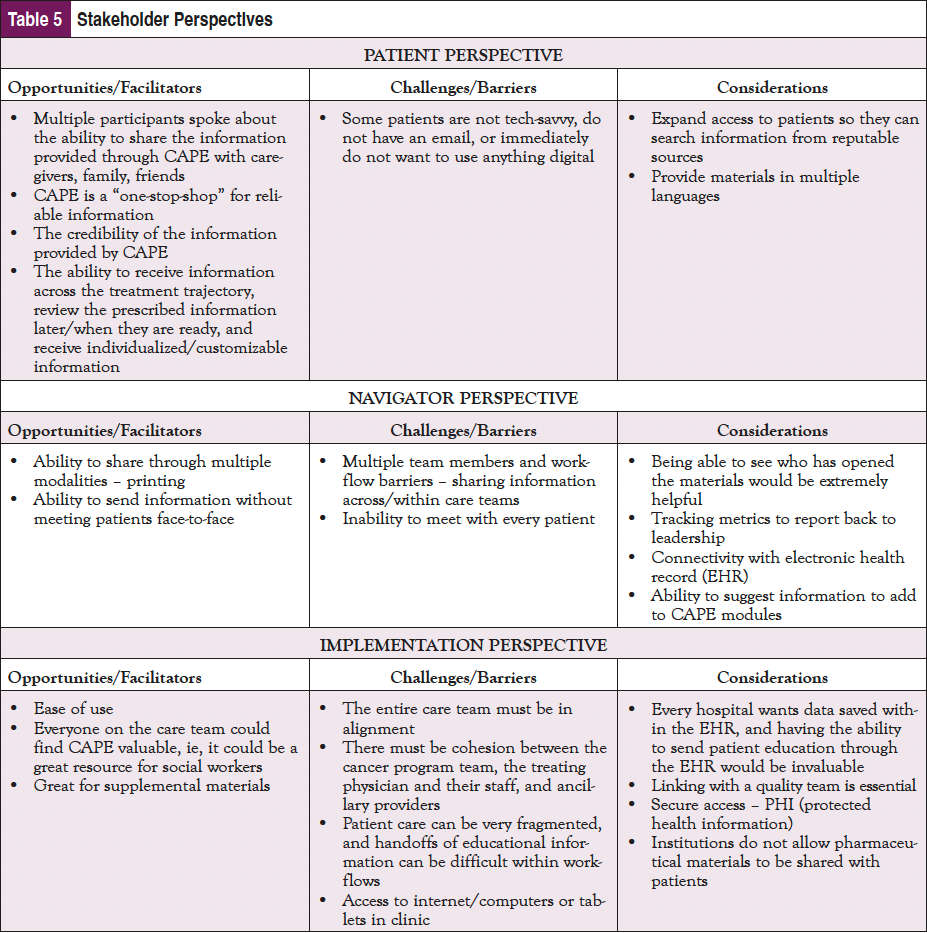

Feedback from the site debriefings was positive, and valuable insights of their experiences were derived from each debrief. Participants shared opportunities/facilitators, challenges/barriers, and considerations/recommendations for future implementation from their experience. Overall, CAPE was well received by all institutions despite varying levels of patient engagement and institutional resources. All sites liked that it is a patient-centered tool and saw a great deal of value in the tool having been developed by AONN+, an organization that they view as trustworthy and reputable. Navigators had heard of other tools similar to CAPE being utilized either within their clinical space or externally. One site expressed that their patients are typically receptive to the printed Lung Cancer Handbook, which serves as the main source of educational material for their NSCLC patients. The navigators felt that although CAPE is user-friendly, the study and consenting aspect was a barrier to patient engagement, and some patients were too overwhelmed to receive more information, especially those who were at a later stage of disease. The navigators loved that all educational information was in 1 place and felt that iPads do/would make implementing CAPE in the future much easier. It was noted that finding the right time to introduce it could be difficult, especially if patients were overwhelmed, but they felt that introducing CAPE within 12 weeks of diagnosis was beneficial. Navigators stated that the added preview button (to view resources prior to sending to patients) was helpful when prescribing patients materials, and a dashboard would make the tool even better in the future. The navigators felt that having the ability to share CAPE with caregivers would be invaluable, especially since not all patients are tech-savvy, and while the ability to print materials was helpful, it may not always be feasible in a clinical setting. In addition, they recommended sending limited amounts of materials to patients per encounter to avoid overwhelming them. Finally, all sites expressed that they had institutional support to utilize CAPE within their clinical settings and are interested in using CAPE in the future with their lung cancer patients, as well as in additional disease sites.

Focus Groups Findings

In addition to the pilot study, a focus group at the AONN+ 2022 Midyear meeting in Austin, TX, was conducted with 10 navigators to evaluate perceptions of the CAPE platform and address additional barriers/solutions to implementation in different oncology clinical settings. Participants were geographically diverse and represented various clinical roles and navigation types. Dr Fleisher’s team administered preread materials consisting of access to the CAPE platform, background information on CAPE, and a presurvey to collect initial thoughts of the platform, and conducted the focus group that centered on patient, navigator, and implementation perspectives. Dialogue from the focus group supported findings from the pilot study and was coded, and key takeaways focusing on opportunities/facilitators, challenges/barriers, and recommendations and considerations from the patient, navigator, and implementation perspective are highlighted in Table 5.

Since the CAPE Lung pilot study, AONN+ has begun expanding into other disease sites, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, renal cell carcinoma, and ovarian and endometrial cancers, and offers the CAPE platform to all AONN+ members.

Limitations

As this project started at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, recruitment was slow and sites had many additional challenges, including new responsibilities to manage the safety of cancer patients while treating patients with COVID. This was a tumultuous time for staff and patients and made it difficult to recruit. However, the sites remained committed to the project, and we were able to achieve a respectable sample for the evaluation. We did not have any posttest data from TFC or Baptist patients given their limited recruitment.

Conclusion/Discussion

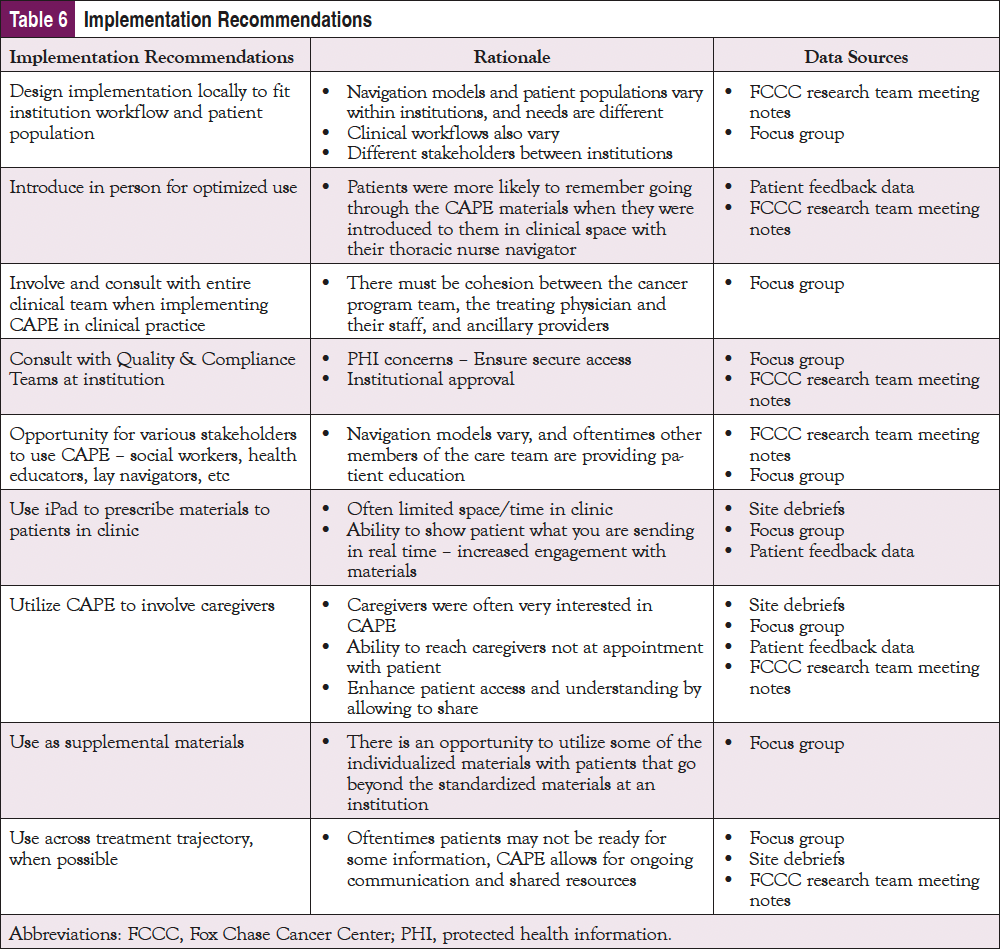

The majority of the patients who used the CAPE resources viewed them positively. However, some patients felt overwhelmed by their diagnosis or other external factors, so their ability to use or absorb the information provided through CAPE was diminished. This provides an important connection between the patient and the navigator and an opportunity to assess the patient’s emotional needs prior to prescribing specific information. In addition, using this tool in conjunction with a navigator or clinical team could increase utilization. Based on these findings, AONN+ believes there are strategic points in the patient care process at which CAPE could be introduced into the treatment trajectory. A one-size-fits-all approach to implementation timing may not be optimal. As shown in Table 6, a number of key implementation recommendations emerged from patient and organizational perspectives.

In addition to evaluating patient efficacy of healthcare delivery interventions, understanding contextual factors when addressing translation to real-world settings is critical for optimal implementation and dissemination. The insights from these findings can guide future implementation and dissemination of CAPE as it expands to different disease sites, and implementation planning and start-up checklists are available on the AONN+ site.

Acknowledgments

Zoe Landau, MPH, Fox Chase Cancer Center; Cheryl Bellomo, MSN, RN, OCN, ONN-CG, Intermountain Healthcare; Amy Jo Pixley, MSN, RN, OCN, ONN-CG; Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health; Ann B. Barshinger Cancer Institute.

Thank you to each of the sites, their navigators and staff, and the patients who participated in this project.

AONN+ acknowledges Takeda Oncology for its support and funding of this innovative, leveraged, and evidence- based program.

References

- Rivera MP, Katki HA, Tanner NT, et al. Addressing disparities in lung cancer screening eligibility and healthcare access. an official American Thoracic Society statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:e95-e112.

- Bellomo C, Pixley AJ, Johnston D. Physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients and caregivers following lung cancer diagnosis: a scoping review. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2019;10(8):296-303.

- Fujinami R, Otis-Green S, Klein L, et al. Quality of life of family caregivers and challenges faced in caring for patients with lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:E210-E220.

- Gould MK. Delays in lung cancer care: time to improve. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1303-1304.

- Lim C, Tsao MS, Leet LW, al. Biomarker testing and time to treatment decision in patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015:26:1415-1421.

- Lall P, Rees R, Law GCY, et al. Influences on the implementation of mobile learning for medical and nursing education: qualitative systematic review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019; 21:e12895.

- Chambers D, Coronado G, Green B, et al. Designing with implementation and dissemination in mind. In: NIH Pragmatic Trials Collaboratory. K. Staman, ed. https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/design/designing-with-implementation-and-dissemination-in-mind/.

- Aapro M, Bossi P, A Dasari, et al. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:4589-4612.

- Ruco A, Dossa F, Tinmouthet J, et al. Social media and mHealth technology for cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e26759.

- Manteghinejad A, Javanmard SH. Challenges and opportunities of digital health in a post-COVID19 world. J Res Med Sci. 2021;26:11.

- Buis L. Implementation: the next giant hurdle to clinical transformation with digital health. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e16259.

- Mathews SC, McShea MJ, Hanleyet CL, al. Digital health: a path to validation. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:38.

- Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337-350.

- Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:228-243.

- Glasgow RE, Battaglia C, McCreightet M, et al. Use of the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to guide iterative adaptations: applications, lessons learned, and future directions. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:959565.

- Bellomo C, Pixley AJ. The CAPE Initiative: developing meaningful educational materials to elevate quality of life for patients with lung cancer. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2019;10(7):260-262.

- Bellomo C, Pixley AJ, Johnston D. Filling an educational void: AONN+ announces Cancer Advocacy & Patient Education (CAPE) lung cancer initiative. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2019;10(12):532-538.

- McCreight MS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, et al. Using the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) to qualitatively assess multilevel contextual factors to help plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate health services programs. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9:1002-1011.

- National Cancer Institute. What is HINTS? https://hints.cancer.gov/.

- Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, et al. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:889-894.

- Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, et al. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:94-99.

- Marcus AC, Diefenbach MA, Stanton AL, et al. Cancer patient and survivor research from the cancer information service research consortium: a preview of three large randomized trials and initial lessons learned. J Health Commun. 2013;18:543-562.

- Bennett C, Graham ID, Kristjansson E, et al. Validation of a preparation for decision making scale. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:130-133.

- Richman AR, Tzeng JP, Carey LA, et al. Knowledge of genomic testing among early-stage breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2011;20:28-35.

- Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberget B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:21.