Kelly N. Owens, PhD1; Marleah Dean, PhD2,3; Elizabeth Bourquardez Clark, MPH2; Piri Welcsh, PhD1; Diane Rose1; Erica S. Kuhn, MPH4; Dennis P. DeBeck, MA2; Jessica Conaty, MPH5; Robin H. Pugh Yi, PhD6; Sue J. Friedman, DVM1; Jennifer Klemp, PhD, MPH7

1Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE), Tampa, FL

2Department of Communication, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL

3Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

4Susan G. Komen, Dallas, TX

5Health Informatics Institute, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL

6Akeso Consulting, Vienna, VA

7Division of Clinical Oncology, University of Kansas Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS; Caris Life Sciences, Irving, TX

Background: Oncology nurse navigators (ONNs) facilitate breast cancer patients’ care via information, resources, and referral services.

Objective: To determine the needs and barriers of ONNs serving young breast cancer (yBC) patients and metastatic breast cancer (mBC) patients.

Methods: Fifty-two active ONNs completed an online needs assessment survey created and reviewed by a multistakeholder working group under the CDC-funded Project EXTRA program.

Results: Familiarity of ONNs with topics relevant for breast cancer patients, referral patterns, and perception of educational needs varied by career stage. Earlier-career ONNs (≤5 years of work experience) were less familiar with clinical trial participation (45% vs 79%; P=.0315) and genetic counseling and testing (73% vs 96%; P=.0431), and referred patients less often to clinical trials (35% vs 89%; P=.0014 for yBC patients, and 36% vs 89%, P=.0028 for mBC patients). ONNs reported substantial barriers to many services, but not to fatigue, menopause management, and pain management. Most ONNs were interested in continuing education for sexual health and intimacy, but not clinical trials, treatment side effects, or pain management. The majority cited a need for patient materials about sexual health and intimacy and mental health issues. Although most ONNs were confident in their ability to address questions about breast cancer in the media, they indicated additional resources would be useful.

Conclusion: Familiarity, referral patterns, educational needs, and barriers faced by earlier-career ONNs differ from later-career ONNs. Site-specific attention to distinct needs of ONNs by job tenure may benefit patient outcomes. Notably, 5 years of work experience appeared to be a meaningful threshold for distinguishing novice and expert ONNs. ONNs expressed significant barriers to referral for clinical trials, most commonly patient understanding of value, suggesting that patient education and materials may reduce this barrier. Improving clinical trial referral (or other site-specific barriers) are actionable steps for ONN programs.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed apart from skin cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States.1 Two important groups among breast cancer patients are young women with breast cancer (yBC), defined as women aged 45 years or younger, and metastatic breast cancer (mBC) patients due to their distinct needs for clinical care and services. Together, they represent approximately one-third of breast cancer patients.2

Challenges for Young Women and Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer

yBC and mBC patients experience distinct but overlapping challenges, including fear, uncertainty, impacts on quality of life, and substantial financial burdens.3-8 Both groups report psychosocial distress9,10 and struggle with quality-of-life issues.9,11 However, the cancer experiences of yBC and mBC patients raise concerns that are distinct from the broader breast cancer patient population. More often than older counterparts, yBC patients face disruptions to family planning, potential emotional and psychological distancing from family and peers, and body image concerns. mBC patients have the additional challenges of facing mortality and end-of-life issues, often intense treatment side effects, and potentially substantial financial burdens. Furthermore, these groups are not mutually exclusive; some yBC patients are also mBC patients and experience unique difficulties because of their cancer.9-11

Oncology nurse navigators (ONNs) are central facilitators of breast cancer care. ONNs provide clinical expertise on cancer issues to support education of patients, facilitate decision-making, and assist with navigating treatment plans.

To cope, yBC and mBC patients often use media and internet resources for healthcare information,12-14 but they may struggle to evaluate confusing and misleading information,15-17 causing distress and impacting decision-making.13,18 Information from family and friends, while well-meaning, may not reflect the intricacies of the cancer experience of yBC or mBC patients.

The Role of Oncology Nurse Navigators in Breast Cancer Care

Oncology nurse navigators (ONNs) are central facilitators of breast cancer care. ONNs provide clinical expertise on cancer issues to support education of patients, facilitate decision-making, and assist with navigating treatment plans. They act as frontline emotional and psychological support for patients.19,20 ONNs also handle diverse aspects of patient needs by providing information and referring patients to clinical services that impact treatment, lifestyle services that impact quality of life, as well as guideline-recommended genetic counseling and testing services.

As a part of a larger effort to support healthcare of yBC and mBC patients, the patient advocacy organization Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE) and researchers at the University of South Florida (USF) created and conducted a needs assessment survey of ONNs serving the breast cancer community. This manuscript reports ONN familiarity with key topics, referral patterns and barriers, and educational and resource needs for facilitating care of yBC and mBC patients.

Methods

ONNs completed a 17-question needs assessment survey (Appendix, click to see) about their experience with yBC and mBC patients in the prior 6 months. The survey was created by our working group of patients, patient advocates, ONNs, and cancer and health communication experts under FORCE’s Project EXTRA. FORCE recruited participants via social media, email, and anonymous link distributed to members of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+). Data were collected through the USF’s Qualtrics survey system from May 4, 2020, to September 30, 2020.

ONN respondents were excluded if they were not practicing ONNs (n=13), were outside the United States (n=2), or provided an incomplete survey (n=34, typically <25% completion). Data were evaluated for statistical significance by 2-tailed Fisher exact test with a significance threshold of P≤.05. Of 52 participants, 46 provided length of work experience; responses from this subgroup were similar to the full cohort for all questions assessed.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Fifty-two ONNs completed the survey. Participants’ workplace included community cancer centers (21, 40%), nonprofit organizations (11, 21%), academic institutions (8, 15%), federally funded health centers (3, 6%), industry (2, 4%), rural settings (6, 11%), and as volunteers (1, 2%). Eleven (21%) worked in multiple settings, and 18 (35%) did not report workplace.

Of 46 ONNs who provided information about work experience, about half had 5 years of experience or less, referred hereafter as “earlier-career ONNs” (n=22, 48%), and about half worked as ONNs for more than 5 years, hereafter “later-career ONNs” (n=24, 52%).

In the prior 6 months, most ONNs saw more yBC than mBC patients—most commonly 10 to 19 yBC (35% of ONNs) and 1 to 4 mBC (34% of ONNs) patients. The volume of yBC or mBC patients did not correlate with work experience. Of note, the overlap between yBC and mBC patients was not determined.

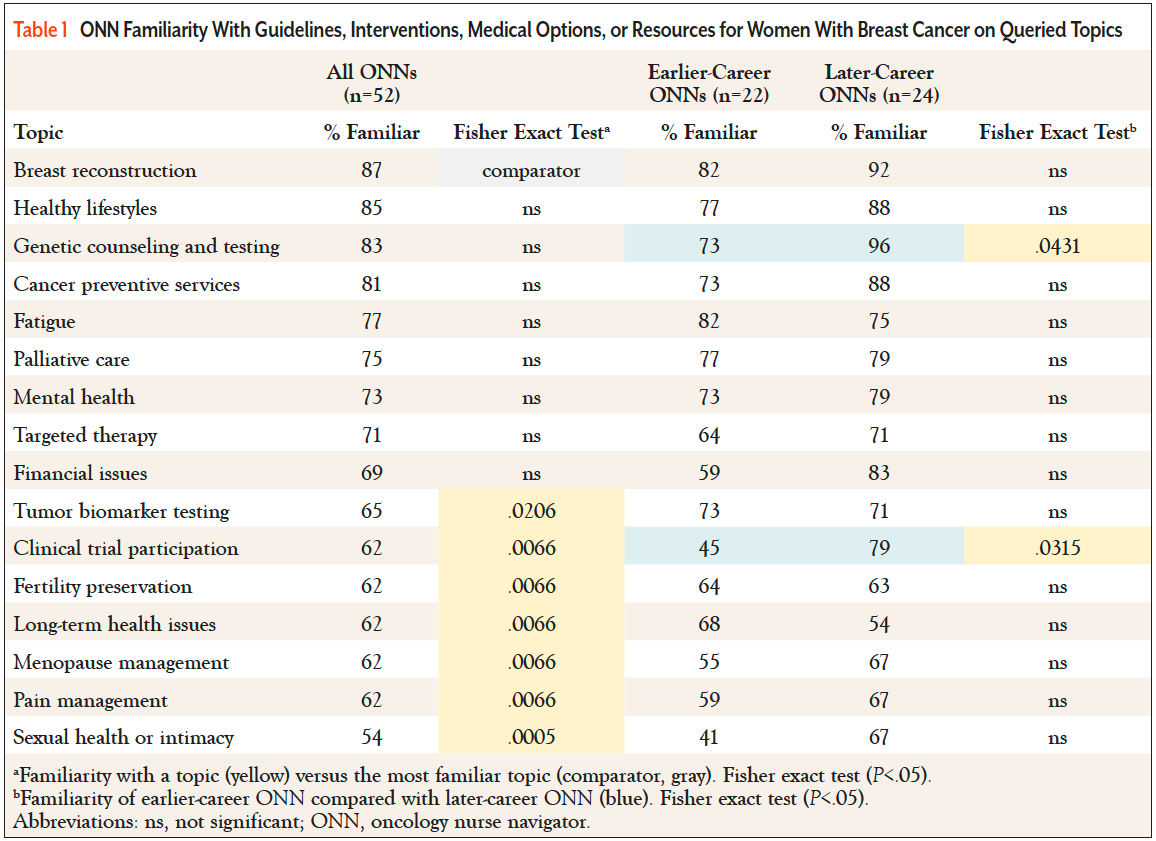

Familiarity With Guidelines, Interventions, Medical Options, and Resources

ONNs reported familiarity with “any guidelines, interventions, medical options, or resources available for women diagnosed with breast cancer” for 16 topics (Table 1). Most ONNs (83%-87%) were familiar with the topics of genetic counseling and testing for inherited mutations, healthy lifestyles, and breast reconstruction. Fewer were familiar with issues related to sexual health or intimacy (54%), pain management (62%), menopause management (62%), long-term health (eg, cardiovascular, bone health, neuropathy [62%]), fertility preservation (62%), clinical trial participation (62%), or tumor biomarkers (65%).

Earlier-career ONNs were less familiar than later-career ONNs for most topics, but this was statistically significant only for clinical trial participation and genetic counseling and testing.

Referral Patterns

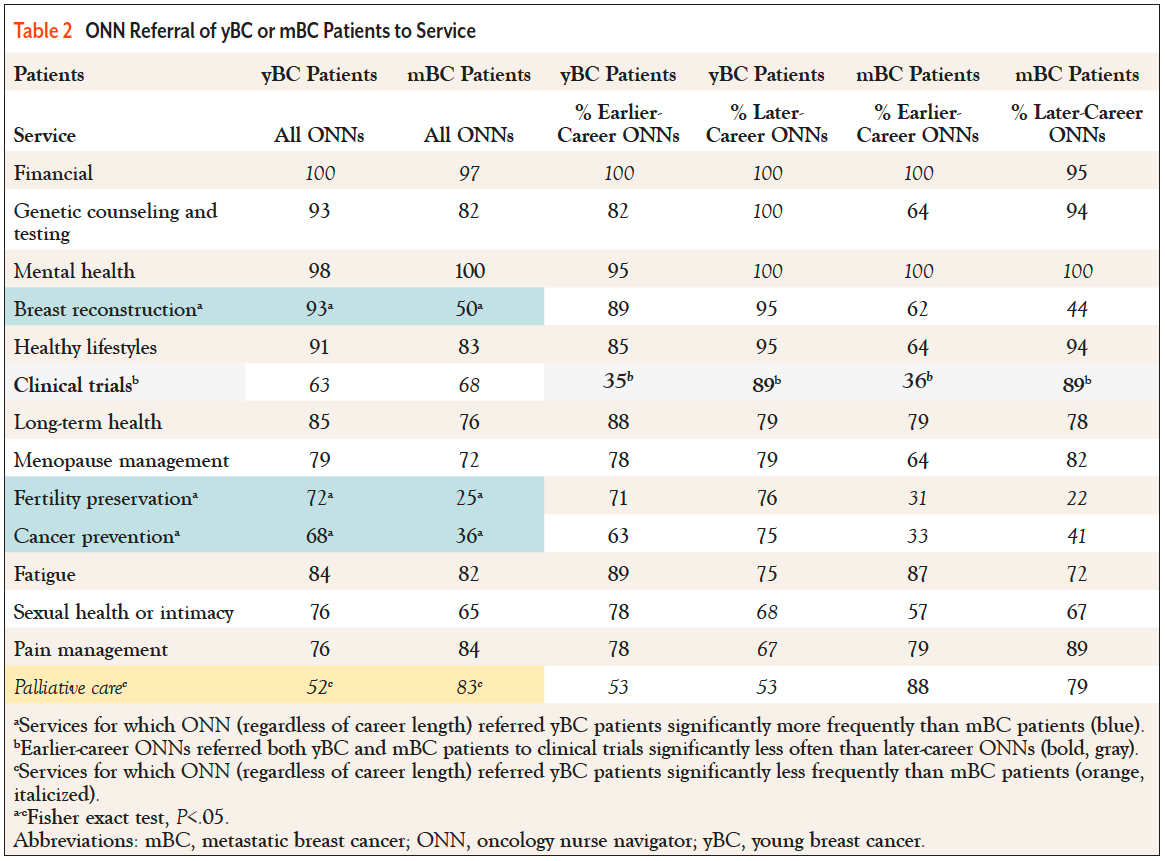

Table 2 shows referral patterns of ONNs for the prior 6 months. Most ONNs referred yBC and mBC patients for financial, mental health, or genetic testing services. For many other services, referral patterns of yBC and mBC patients differed. ONNs referred yBC patients more frequently (Table 2, blue bars) than mBC patients to breast reconstruction (P=.00001), fertility preservation (P<.00001), and cancer prevention services (P=.0091), and less often to palliative care (Table 2, orange bars; P=.0048).

For some topics, referral patterns differed by ONNs’ career stage. Earlier-career ONNs referred yBC and mBC patients significantly less frequently to clinical trials than later-career ONNs (35% vs 89%, P=.0014 for yBC patients; 36% vs 89%, P=.0028 for mBC patients). While not statistically significant, earlier-career ONNs tended to refer mBC patients less often than yBC patients for genetic counseling and testing, healthy lifestyles, menopause management, and sexual health or intimacy services. In contrast, later-career ONNs referred yBC and mBC patients at similar rates.

Barriers to Referrals

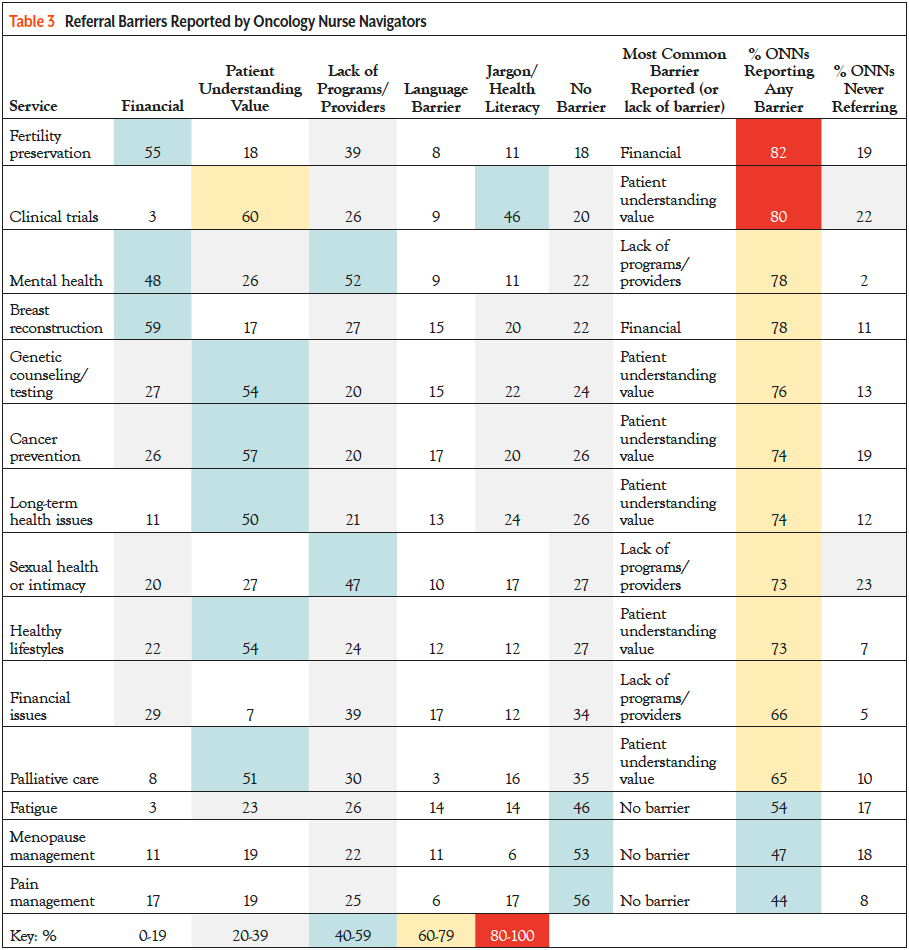

ONNs reported referral barriers for 14 services (Table 3). Barriers included finances, patient understanding of value (ie, not understanding what the service was, its potential uses or impact), lack of local programs or providers, language, and medical jargon/health literacy. The majority cited at least 1 referral barrier for 12 of 14 services, often citing multiple barriers.

The services for which ONNs most frequently reported barriers were fertility preservation (predominantly financial and lack of programs/providers) and clinical trial services (patient understanding of value and medical jargon/health literacy barriers). Notably, clinical trial participation was the only service for which ONNs reported medical jargon/health literacy as a substantial barrier.

ONNs referred patients infrequently to some services despite reporting few barriers. Most ONNs indicated there was no barrier to referral for menopause management and pain management services (no barrier was reported twice as often as any individual barrier). And yet, 17% to 18% of ONNs never referred patients for fatigue or menopause management services (Table 3). This observation contrasts with breast cancer patients’ reports that these services are frequently needed.21

For several services, the greatest barrier was lack of “patient understanding of value.” This may reflect patients misunderstanding what the service entails or its potential impact on cancer care. Although ONNs indicated that patient understanding of value was a referral barrier for cancer prevention and genetic counseling and testing, ONNs indicated they were familiar with these services and could readily refer patients, suggesting these may be useful areas to target for patient education efforts. In contrast, for healthy lifestyles, long-term health issues, and palliative care services, ONNs also indicated their own lack of familiarity, suggesting a need for continuing education opportunities on these topics.

Finally, most ONNs (60%) indicated “patient understanding of value” was the greatest barrier for clinical trial referrals, followed by medical jargon/health literacy and lack of local programs/providers. Furthermore, 22% of ONNs never referred patients for clinical trial participation. Together, these findings suggest that ONNs may benefit from additional support for navigating patients to clinical trial participation.

Education Needs and Patient Support

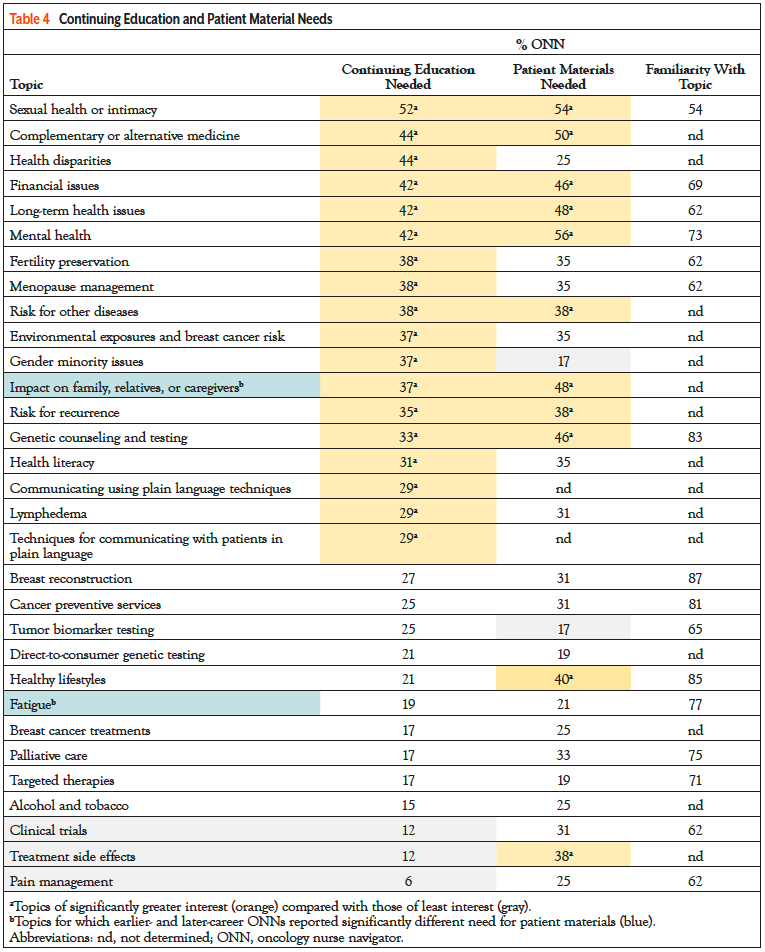

Table 4 summarizes ONNs’ interest in continuing education and patient education topics (orange bars highlight topics of significant interest). The majority were interested in continuing education about sexual health and intimacy and not interested in topics of clinical trials, palliative care, targeted therapies, and alcohol and tobacco use. Earlier- and later-career ONNs reported similar continuing education interests—despite differences in familiarity. The most requested topics for patient education materials were mental health, sexual health/intimacy, and complementary/alternative medicine, paralleling interests in continuing education. ONNs reported needing patient materials about healthy lifestyles and palliative care, despite low interest in corresponding continuing education opportunities. Last, earlier-career ONNs more frequently cited a need for patient materials than their later-career counterparts about fatigue (41% vs 4%) and impacts on family or caregivers (68% vs 33%).

Breast Cancer Information in the Media

Clarifying information and educating patients is an important role of ONNs. Most ONNs (67%) discussed media articles with 1 to 4 breast cancer patients during the prior 6 months. Earlier-career ONNs were less likely to discuss media articles with patients than later-career ONNs (77% vs 96%). More later-career ONNs (25%) discussed media articles with 10 or more patients in the prior 6 months than earlier-career ONNs (5%).

Regardless of discussion frequency, most ONNs (89%) were somewhat or very confident in their ability to address patients’ media-related questions. However, almost all ONNs (94%) indicated information about media articles on specific breast cancer topics would be useful, particularly current guidelines.

ONNs were asked about FORCE’s XRAY—eXamining Research Articles for You—program,22 which reviews scientific studies and media articles about breast cancer and provides plain language summaries, relevance ratings, questions for healthcare providers, related clinical trials, guidelines, and resources. Overall, ONNs indicated the XRAY program was an effective tool for understanding media about breast cancer, but only 17% of ONNs (9 of 52) were familiar with the XRAY program, and few (7 of 52, 13%) had used it. Among this small group, 94% indicated that XRAY review features were “very” or “somewhat useful,” particularly the summary, relevance ratings, expert guidelines, and printer-friendly version. All noted features tailored for ONNs (eg, questions most asked by patients, continuing education opportunities, related patient services, and key issues) would be useful.

Discussion

This study reports the needs and barriers of ONNs when facilitating care for yBC and mBC patients. We discuss key findings, limitations, and how these inform future advocacy and education efforts.

First, ONNs’ familiarity with breast cancer–related topics differed with work experience. Earlier-career ONNs were less familiar with clinical trial participation and genetic counseling and testing, while later-career ONNs were less familiar with fertility preservation and long-term health issues. The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) defines a “novice ONN” as a nurse who has worked 2 years or less as an ONN and continues to build upon prior training and an “expert ONN” as a nurse who has worked “at least 3 years, is proficient in the role, and has the education and experience to use critical thinking and decision-making skills pertaining to the evolution of navigation processes....”20 We found ONNs’ familiarity with topics, referral of services, and perception of education differed depending on career stage. These findings suggest that 5 years of work experience may be a more useful threshold for distinguishing novice and expert ONNs.

Differences associated with career stage may indicate areas where more emphasis is needed during training or early mentorship, or, for later-career ONNs, may reflect changes in practice since training or a lack of clinical use or continuing education opportunities.

Lack of interest in palliative care may reflect confusion between palliative care and hospice or end-of-life care. Therefore, service-specific efforts to increase patient awareness and improve understanding of value may help.

ONNs’ familiarity with topics did not always align with continuing education interest. For example, ONNs reported less interest in continuing education about clinical trial participation despite a lack of familiarity; future research could explore this discrepancy and how to improve engagement. These findings may help organizations such as AONN+ and ONS target training programs for earlier-career development (eg, sexual health or intimacy and clinical trial participation) and later-career ONNs (eg, fertility preservation and long-term health).

Second, a key role of ONNs is helping patients and their families navigate healthcare system barriers.20 It is telling that ONNs reported multiple and significant barriers to most support services. “Patient understanding of value” was perceived as a significant barrier to referral for many services; however, the underlying reasons may vary between services. For example, patients’ lack of interest in genetic counseling and testing may be due to a lack of understanding of how inherited mutation status impacts cancer treatment or relatives’ health. Lack of interest in palliative care may reflect confusion between palliative care, which includes serious but nonterminal disease, and hospice or end-of-life care. Therefore, service-specific efforts to increase patient awareness and improve understanding of value may help.

More research is needed to determine how to overcome referral barriers and enhance access through all stages of a patient’s treatment.23 Surprisingly, language and medical jargon/health literacy were not barriers for most services, apart from clinical trial participation, where medical jargon was a common barrier.

Third, ONNs reported significant referral barriers to clinical trial participation. Earlier-career ONNs reported less familiarity and fewer referrals compared with later-career ONNs. The ONS defines this as a core competency for novice ONNs,20 so these results highlight an unmet need. Although few ONNs were interested in continuing education about clinical trials, they reported a desire for related patient materials. The greatest referral barriers to clinical trial participation were “patient understanding of value” and medical jargon/health literacy barriers. Therefore, providing patient-friendly, plain-language materials about the value of clinical trial participation might reduce these barriers and increase referrals to clinical trials.

Adapting efforts according to ONN career stage may be an important component for continuing education. For clinical trial participation, patientfriendly materials may help reduce barriers to referral and participation.

Last, ONNs reported wanting additional resources—tailored to their care needs—to help discuss media articles with patients. This supports previous literature indicating yBC patients have unique needs and can be overwhelmed by media information14,17 and reinforces the importance of helping mBC patients locate credible, reliable media and online health information. To this end, FORCE continues to revise the XRAY program to expand its reach and support healthcare providers and patients.

Limitations

This was a small pilot study, which limits its generalizability. Additionally, data were collected via an online survey (due in part to the pandemic), which limited the ability to ask respondents clarifying questions. However, this study provides a valuable baseline for understanding the needs of ONNs and barriers to referral services for yBC and mBC patients.

Conclusion

Understanding ONNs’ needs and barriers can guide development of educational curricula for ONNs and their patients. Most ONNs were confident in addressing patients’ questions about media reports on breast cancer but indicated they would welcome additional resources. Understanding barriers to information and referrals is necessary to develop approaches to reduce educational gaps and lower referral barriers. Adapting efforts according to ONN career stage may be an important component for continuing education. For clinical trial participation, patient-friendly materials may help reduce barriers to referral and participation. ONN programs may benefit from local evaluation of how tenure impacts the needs of ONNs, how gaps between topic familiarity and continuing education interests indicate areas for ONN and/or patient education, and how targeting barriers to referral services may improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the oncology nurse navigators who participated in this study and AONN+ for disseminating the needs assessment survey.

Ethics Statement and Informed Consent: The study was approved as an exempt protocol by USF IRB (Protocol #000339). Study processes were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Declaration of Interest: None of the authors reported any conflict of interest.

Contributions

Kelly N. Owens: conceptualization, survey development, methodology, writing—drafting, writing—review and editing, statistical analysis, funding acquisition.

Marleah Dean: conceptualization, survey development, methodology, writing—drafting, writing—review and editing, supervision, resources, funding acquisition.

Elizabeth Bourquardez Clark: methodology, survey development, writing—review and editing.

Dennis P. DeBeck: writing—drafting, writing—review and editing.

Jessica Conaty: survey development, methodology, writing—review and editing.

Piri Welcsh: conceptualization, survey development, writing—review editing, funding acquisition.

Diane Rose: conceptualization, survey development, writing—review editing.

Erica S. Kuhn: conceptualization, survey development, writing—review editing.

Sue J. Friedman: conceptualization, methodology, writing—drafting, writing—review and editing, supervision, resources, funding acquisition.

Robin H. Pugh Yi: conceptualization, survey development, review and editing.

Jennifer Klemp: conceptualization, review and editing.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by Cooperative Agreement Number DP006677 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Principal Investigator Sue J. Friedman and Site Co-Principal Investigator Marleah Dean, Project Title: Expanding XRAYS ThRough Alliances: Project EXTRA. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for breast cancer: How common is breast cancer? www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

- Fernandes-Taylor S, Adesoye T, Bloom JR. Managing psychosocial issues faced by young women with breast cancer at the time of diagnosis and during active treatment. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:279-284.

- Freedman RA, Partridge AH. Management of breast cancer in very young women. Breast. 2013;22(suppl 2):S176-S179.

- Jacobsen PB, Nipp RD, Ganz PA. Addressing the survivorship care needs of patients receiving extended cancer treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:674-683.

- Krigel S, Myers J, Befort C, et al. ‘Cancer changes everything!’ Exploring the lived experiences of women with metastatic breast cancer. Intl J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20:334-342.

- Rotter J, Spencer JC, Wheeler SB. Financial toxicity in advanced and metastatic cancer: overburdened and underprepared. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e300-e307.

- Spoozak L, Wulff-Burchfield E, Brooks JV. Rallying cry from the place in between. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:451-452.

- Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, et al. Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:320-326.

- Mosher CE, Johnson C, Dickler M, et al. Living with metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative analysis of physical, psychological, and social sequelae. Breast J. 2013;19:285-292.

- Grabsch B, Clarke DM, Love A, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:47-56.

- Corneliussen-James CD. International survey identifies key support and lifestyle needs of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients. The Breast. 2011; 20:S53.

- Lleras de Frutos M, Casellas-Grau A, Sumalla EC, et al. A systematic and comprehensive review of internet use in cancer patients: psychological factors. Psychooncology. 2020;29:6-16.

- Pugh Yi RH, Rezende LF, Huynh J, et al. XRAYS (eXamining Relevance of Articles to Young Survivors) Program survey of information needs and media use by young breast cancer survivors and young women at high-risk for breast cancer. Health Commun. 2018;33:1525-1530.

- Fergie G, Hunt K, Hilton S. What young people want from health-related online resources: a focus group study. J Youth Stud. 2013;16:579-596.

- Laugesen J, Hassanein K, Yuan Y. The impact of internet health information on patient compliance: a research model and an empirical study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e143.

- Pugh Yi RH, Rezende L, Dearfield CT, et al. Results of a pilot test of effects of an online resource on lay audience understanding of media reports on breast cancer research. Health Education Journal. 2019;78:607-617.

- Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Węgierek P. The impact of online health information on patient health behaviours and making decisions concerning health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:880.

- Tay LH, Ong AKW, Lang DSP. Experiences of adult cancer patients receiving counseling from nurses: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16:1965-2012.

- Oncology Nursing Society. 2017 Oncology Nurse Navigator Core Competencies. 2017. www.ons.org/sites/default/files/2017ONNcompetencies.pdf

- Schmid-Büchi S, Halfens RJG, Dassen T, van den Borne B. A review of psychosocial needs of breast-cancer patients and their relatives. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2895-2909.

- FORCE. 2023. XRAY—eXamining Research Articles for You—program. www.facingourrisk.org/XRAY

- Kelly R. Defining the role of the oncology nurse and patient navigator. Blog published by the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators. February 23, 2021. www.aonnonline.org/blog/3609:defining-the- role-of-the- oncology-nurse-and-patient-navigator