Samantha Curriero, MPH1; Kate Konkle, MPH2; Nirmal Ahuja, DrPH2,3; Eugene J. Lengerich, VMD, MS2,4,5

1Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD

2Penn State Cancer Institute, Hershey, PA

3Department of Biobehavioral Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Education,

The Pennsylvania State University, Middletown, PA

4Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA

5Department of Family and Community Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA

Background: Patient navigation (PN) improves cancer-related care, especially care among vulnerable populations who have limited access to medical and preventive care. The Cancer Navigation and Survivorship Network (CaNSuN), established in 2018, aims to connect, educate, and share evidence-based practices among navigators in Pennsylvania.

Objectives: To conduct an environmental scan to increase understanding of navigation in Pennsylvania and identify strategies to better support and strengthen PN. The scan sought to describe characteristics of navigators, funding for and primary location of PN, measures of success, and important challenges.

Methods: A 19-question survey was developed, piloted, and then administered in September 2021. The survey was initially distributed to the 169 CaNSuN newsletter subscribers and members of the Pennsylvania Cancer Coalition with a request to complete the survey and distribute the survey to colleagues. Additionally, requests were emailed to health system partners, state Department of Health, American Cancer Society, and community-based organizations. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted.

Results: Of the 82 complete responses, 77% were from nurse navigators and community health workers and were almost equally divided between working in community, clinical, and hospital settings. Navigators reported being in the field, on average, for 6 years. Challenges identified were lack of clarity on the role (32%), lack of guidelines for navigation (28%), measuring program success (28%), and funding (25%). About 40% reported their positions were funded by a hospital, and 20% by nonprofits. Patient satisfaction (50%) and time to treatment (24%) were the most common measures used to evaluate success. Significant relationships were observed between the navigator type and work setting, involvement at different stages of the cancer continuum, evaluation methods, and challenges.

Conclusion: Results identified opportunities to strengthen support for both navigators and navigation systems in Pennsylvania. Navigation is a growing field with many navigators being new to the role. Groups like CaNSuN can provide professional development and facilitate a statewide learning community of navigators. CaNSuN can advocate for systems and policy change that will better support PN.

Patient navigation (PN) has been shown to reduce the morbidity for cancer patients and to address cancer health disparities within a community.1-3 Historically, a patient navigator has been broadly described as a trained professional who provides one-on-one assistance and support to a patient, thereby facilitating transitions and care throughout the healthcare system.4-6 Prior studies have highlighted the efficacy of PN to improve cancer screening rates and timeliness of initial treatment, increase adherence to follow-up visits with health professionals and, ultimately, improve health outcomes.3,7-9 The number of healthcare systems in the United States with a PN program has increased since the introduction of PN over 3 decades ago.

However, several challenges restrain additional improvement of PN. First, the size and sustainability of cancer navigation programs in cancer centers are variable,10 thus navigators may feel professionally isolated and vulnerable. This fragmented approach may contribute to PN programs being poorly funded.11,12 Second, while patients may benefit from local community services or even services from another healthcare system, a patient navigator within a healthcare system may have little awareness of dispersed community resources or healthcare services, especially if the patient resides a long distance from the navigator’s place of work, as often happens for patients from rural communities. Finally, many states, including Pennsylvania, lack statewide support to train and equip navigators who provide a variety of services and at different points along the cancer control continuum.8,13

While the structure and impact of navigation within an individual healthcare system have been studied previously,8,9,13-21 less attention has been given to the development and study of navigation programs across healthcare systems and those within a specific state. Recognizing the need for a central source of evidence-based resources, applied research, and timely communication for cancer patient navigators throughout Pennsylvania, the Penn State Cancer Institute established the Cancer Navigation and Survivorship Network (CaNSuN) in Pennsylvania in 2018. CaNSuN’s mission is to connect, educate, share, and enhance evidence-based practice among patient navigators in Pennsylvania. By understanding how navigation programs operate on a state level, groups like CaNSuN can implement initiatives and advocate for policies to improve cancer PN throughout a state.

To better understand the scope and practice of cancer PN in Pennsylvania, CaNSuN conducted an environmental scan of cancer navigation programs across the state. An environmental scan is the process of collecting information regarding program development and implementation to better understand the gaps and trends to make future informed strategic decisions.22,23 The objectives of this manuscript are to: (a) report the results of that environmental scan; (b) identify challenges and potential strategies to overcome them and to better support and strengthen PN in Pennsylvania; and (c) establish a baseline to gauge and help direct future cancer PN-related research within Pennsylvania.

Methods

Survey Development

We developed, piloted, and administered a survey to collect data on cancer, PN programs across Pennsylvania. To inform survey development, we conducted a literature search using key words “patient navigation,” “navigation in Pennsylvania,” and “patient navigation environmental scans” to identify articles that had assessed PN. We drafted a 19-question survey that was then divided into 3 sections (demographics, individual-level, and program-level) and piloted with colleagues and key partners. After assessment of response latency, accuracy, potential errors and ambiguous words, the survey was finalized. Institutional review board exemption for human subjects research was granted by The Pennsylvania State University (STUDY00018488). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine.24

Survey Measures

The survey was divided into 3 primary areas: demographics, individual-level, and program-level characteristics to understand the multidimensional and interactive effects that impact navigators and navigation systems. Survey participants were asked to respond to questions related to their demographic characteristics (such as type of navigator, organization worked for, work setting, and regional location), their individual-level characteristics as a navigator (such as years of experience, point of care in the care continuum, number of individuals served, and demographics of patients served), and characteristics of their PN program (such as type of evaluation method, length of program existence, type of referral process, funding mechanism, and substantial challenges experienced).

Questions including years of experience, number of patients navigated per month, and length of program existence were presented as either a number or a range. Responses “Unsure” or “I don’t know” were excluded from data analysis. Questions including type of data collection method, work setting, and delivery method in the individual-level navigator section were limited to those who responded “yes” to navigating patients. In all other instances, questions including referral process, funding mechanism, length of program existence, and most substantial challenges were given to all participants. Response options for these questions were prepopulated with choices that emerged from prior network discussions and feedback during the survey development process. We chose to use preselected responses to increase response rate, and when appropriate, offered the option to select “Unable to Answer,” “N/A” (for not applicable), or provided an opportunity for a written response as “Other.”

Sample Population

The target audience was CaNSuN members or their colleagues and those involved in cancer PN. Our survey, developed prior to release of the Oncology Navigation Standards of Practice,25 asked respondents to characterize themselves as a nurse navigator, community health worker (CHW), social worker, financial navigator, lay navigator, nutrition navigator, manager of navigators, or other. For our analysis to be consistent with the recent professional standards, we grouped the data during bivariate analysis into patient navigators (CHWs/lay navigators), nurse navigators, and others. The survey was initially distributed to CaNSuN’s 169 newsletter subscribers and the Pennsylvania Cancer Coalition with a request to both complete the survey and to share it with colleagues, emulating a convenience snowball sampling process. Additional emails were sent to key partners from health systems, the state Department of Health, American Cancer Society, and other community-based organizations with a request to distribute to navigators. Weekly reminders were sent to the email list, and the survey was closed after 3 weeks when responses slowed considerably. The survey was open from September 9, 2021, through September 30, 2021.

Data Analysis

One hundred three individuals responded to the survey; 21 responses were excluded from data analyses because participants completed fewer than 50% of the questions, not including the section on individual-level navigator information. In total, 82 responses were summarized in the following analysis. Nonresponses to questions were reported as missing data. Given the low frequency count in some of the responses, the navigators were grouped into 3 categories. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 predictive analytics software. Descriptive analysis was conducted to identify the frequency of variables. Further, bivariate analyses were applied to evaluate the relationship between navigation characteristics and type of navigator. Chi-square test was applied to determine potential relationship with a two-sided significance level of P<.05.

Results

Demographic and Individual-Level Navigator Characteristics

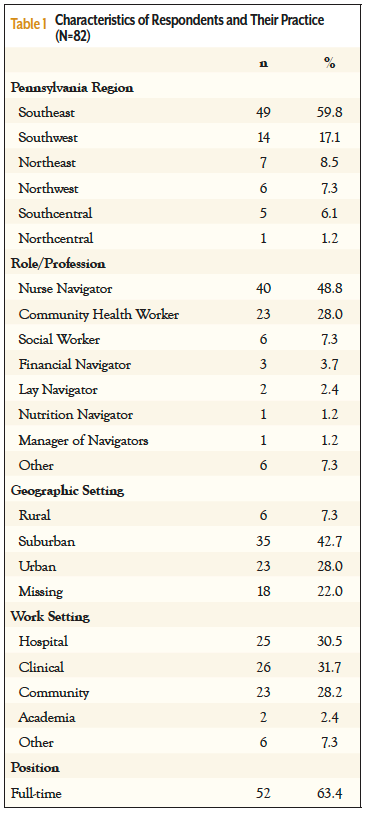

A total of 82 individuals from 25 organizations and representing all 6 Pennsylvania Department of Health specified regions responded to the survey (Table 1). Approximately 76% were from the most populated regions (southeast and southwest) of Pennsylvania. More than 80% of the respondents were either nurse navigators (48.8%), CHWs (28%), or social workers (7.3%). In addition, 30.5% of respondents reported working in a hospital, 31.7% in a clinic, 28.2% in the community, and 9.7% in other settings.

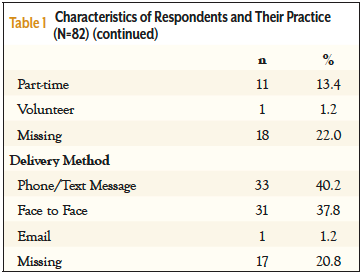

The average time as a navigator was 6.1 years (median 5 years, range <1 to 30 years). The majority of respondents (52, 63.4%) reported a full-time position, with 11 (13.4%) working in a part-time position. One individual reported working as a volunteer (18 values were missing). Phone/text message was the most popular method for delivery of PN (40.2%), followed by face-to-face (37.8%), with email the least used method (1.2%).

Program-Level Characteristics

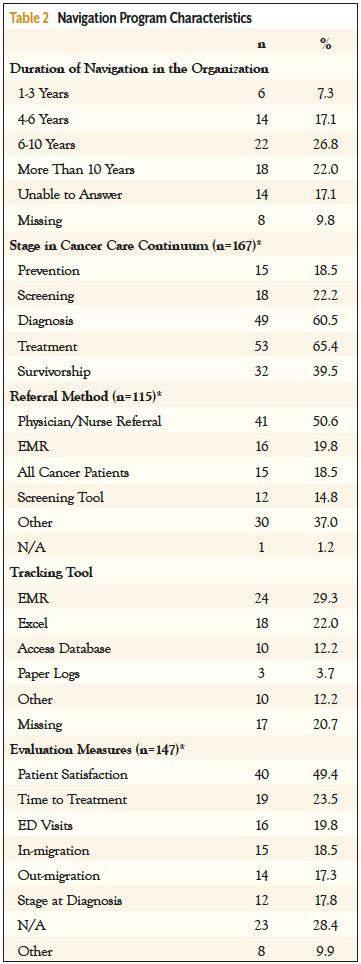

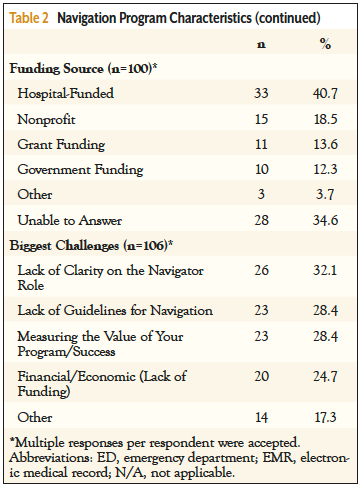

Twenty-two percent of navigators reported working in a program that has been in existence for at least 10 years, and 26.8% reported working in a program that has been in place for 6 to 10 years. About one-fourth (24.4%) reported working in a program that has been in place for less than 6 years (Table 2).

Navigators were asked to select all areas of the cancer continuum in which they worked. There were responses in all areas, with most working in diagnosis and treatment, and fewer focusing on prevention and screening. A majority of patients were referred to PN by a physician/nurse 50.6% (n=41). The mean (median) number of individuals navigated per month was 75.6 (45), with a range of 1 to 500 (20 values were missing) (data not shown). When asked about their primary tracking tool for navigation, 29.3% of participants reported using the electronic medical record, 22.0% used Excel, and 3.7% participants used paper logs.

Respondents worked with a wide range of individuals from populations who experience disproportionately worse cancer outcomes, including African Americans (79.3%), Hispanics (73.2%), non-English speakers (68.3%), and rural populations (68.3%) (data not shown).

Patient satisfaction (49.4%) and time to treatment (23.5%) were the most common measures used to evaluate PN. Approximately 41% reported that their positions were funded by a hospital, 18.5% by nonprofits, 13.6% by grants, and 12.3% by government. The biggest challenges reported were lack of clarity on the navigator role (32.1%), measurement of the value of program/success (28.4%), and lack of guidelines for navigation (28.4%).

Characteristics by Role

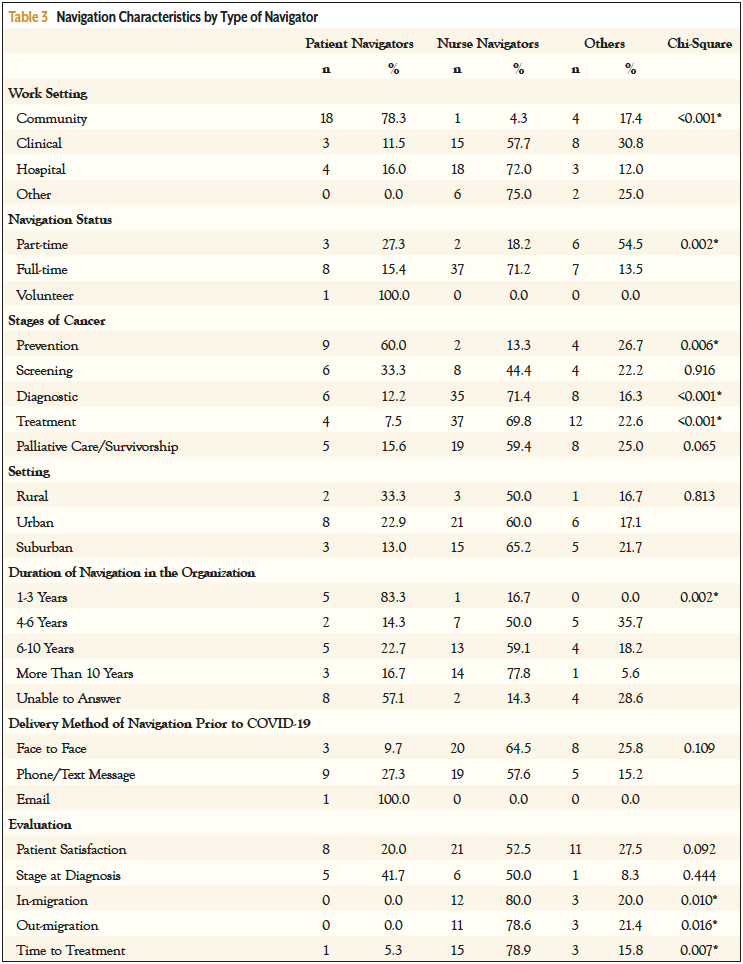

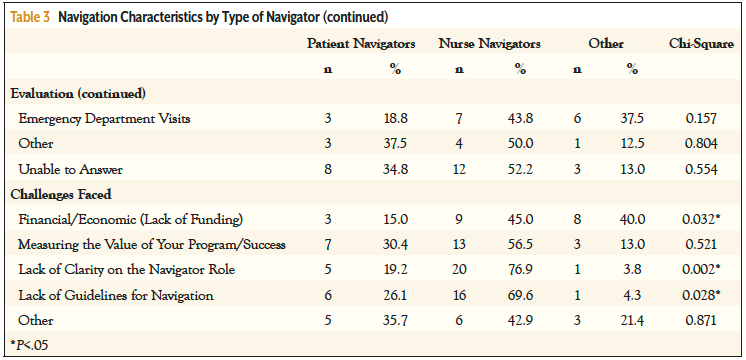

A significant relationship was observed between the navigator type and work setting, involvement at different stages of cancer, evaluation methods, and challenges. The majority (78.3%) of the navigators working in the community settings were patient navigators, whereas nurse navigators were working either in clinical or hospital settings (Table 3). Because the majority of the respondents were either nurse navigators or patient navigators, the stages of navigation involvement were diagnostic and treatment for nurse navigators and prevention for patient navigators. Lastly, lack of clarity in their roles, lack of funding, and lack of guidelines were identified as common challenges by patient navigators and nurse navigators.

Discussion

This study contributes to our understanding of PN in Pennsylvania and fills a gap in the literature regarding state-level analysis of PN programs. Navigators work in several roles, work across the full cancer care continuum, and in various settings. However, the majority of respondents worked in clinical spaces and with patients through diagnosis and treatment. Given the variety of backgrounds of navigators, it is not surprising that the 2 most frequently cited challenges were lack of clarity on the navigator role and lack of guidelines for navigation. Common challenges were reluctance and resistance to the navigation program, and execution.

Navigation programs also varied, starting with which patients are seen. In some programs all patients meet with a navigator at least once, some use a screening tool to determine which patients are seen, while the majority (50.7%) use physician and nurse referrals. While many (29%) used electronic medical records for tracking patients, 44% were using databases such as Access and Excel, and 3.7% used paper tracking, making information more challenging to share with a care team.

The survey results provide insights into the sustainability of navigation programs in Pennsylvania. Garfield et al10 examined measures of sustainability for oncology navigation programs, specifically, program existence greater than 5 years, reliance on sustainable funding, and participation in alternative payment programs. Our survey asked about the first 2 measures and found that 48.8% of respondents reported being part of navigation programs that have been in existence for more than 6 years; our response options did not fully align with the measures in Garfield et al published after our survey. We also found that 40.7% were hospital-funded. Thirty percent reported programs meeting both of those sustainability criteria.

The survey identified opportunities for strengthening navigation programs at the individual- and program-level in Pennsylvania, such as facilitating professional development and mentoring opportunities, clarifying roles and guidelines for navigators, strengthening program evaluation, and building and strengthening connections between clinical and community navigation programs to improve connections to community resources.

Supporting Navigators

The survey found that many navigators are newer to their roles, indicating the need for professional development and educational resources for navigators and providing opportunities for navigators to share learning experiences. CaNSuN can provide a supportive environment for learning and professional development. Creating connections between navigators can help to facilitate warm handoffs if patients move between providers and can also create opportunity to share knowledge of resources and “tricks of the trade.” Given that many navigators work in small teams, or in fragmented systems, a professional network can fill a gap that may otherwise be missing.

CHWs were the second largest group of respondents and reported, more than any other group, working across the entire cancer care continuum. CHWs can have a key role linking patients to community-based resources. However, research has shown that there is immense variability in CHW programs and overlapping expectations and understanding of the CHW role.26 It is important to note that while CHWs may have a PN role, they have a specific designated workforce classification27 and a professional organization, the National Association of Community Health Workers.28 Therefore, it is important to implement strategies to support and integrate CHWs into the navigation system. The inclusion of CHWs in CaNSuN can help to facilitate relationships between CHWs and clinically based navigators.

Strengthening the Navigation System

In addition to directly supporting navigators through network opportunities, education, and outreach, attention should also be given to strengthening the navigation systems in which navigators work. Three key areas for this are supporting policy to better define the navigator’s role, collection of data that will help demonstrate navigation value, and strategies to improve funding for navigation.

According to Ahuja et al,13 PN has not been a standardized profession in Pennsylvania, and there is substantial variation in its practice. Although this variability allows for flexibility based on system and/or patient needs, it was recognized as a challenge to create navigation guidelines and policies in Pennsylvania. However, in 2022, the Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice were released.25 The standards articulate the knowledge and skills that all professional navigators, based upon experience, should possess to deliver high-quality, competent, and ethical services to people impacted by cancer.29 They provide benchmarks for use by healthcare employers and information for policy and decision makers, as well as other health professionals and the public to understand the role of professional oncology navigators. These standards will inform the proposed 2024 changes in navigation reimbursement by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. CaNSuN has the potential to be a voice for navigators within the Pennsylvania Cancer Coalition and the completion of the 2023-2033 Pennsylvania Cancer Plan.30

Adequate collection and evaluation of PN metrics are pivotal in providing justification for supporting PN programs and ensuring navigation is effective at improving care, and therefore outcomes.31 Recently, Paskett et al32 stated that there is enough evidence on the benefits of PN. However, our survey, conducted in 2021, revealed that nearly half of respondents utilized patient satisfaction to evaluate their program. Although this metric is essential, it does not convey the full picture of the importance of PN. Additionally, our survey highlighted that many navigators did not evaluate their navigation program or were unaware of what metrics might be collected. This may include some of the CHWs who are working within the community rather than in clinical settings. Recently, navigation metrics have been developed and disseminated.33 Again, CaNSuN can play an important role through education and training to promulgate navigation metrics throughout Pennsylvania.

Patient navigators and nurse navigators both identified lack of funding as an important challenge. PN programs require financial resources to maintain their operations and expand their reach. Without adequate funding, existing programs may struggle to provide services, and new programs may not be established, limiting access to much-needed support for cancer patients. However, recent research has demonstrated a positive return on investment of cancer PN.12,34

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our sample was diverse with representation from all 6 regions within Pennsylvania. In addition, survey results were adapted to reflect recent changes in the practice of PN. These data support Pennsylvania, working through CaNSuN, joining other state and local PN networks.35

Our survey did have limitations. The survey was a convenience sample of patient navigators in Pennsylvania, making it difficult to generalize the data. Respondent bias may have been present. The survey was open for a short period. Survey questions were not validated. Despite these limitations, this research provided insight into the landscape of cancer PN in Pennsylvania.

Future Directions

This study provided a baseline understanding of cancer navigation programs, and the navigators working in them, in Pennsylvania. The results have captured baseline data that can be used to better support and strengthen PN in Pennsylvania. Future research could focus on implementation of professional standards, program sustainability, and navigation metrics in Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Penn State Cancer Institute’s Office for Cancer Health Equity, the CaNSuN Steering Committee, the Pennsylvania Comprehensive Cancer Control Program, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Department of Health, and the Pennsylvania Cancer Coalition for their contributions to this work.

Funding Sources: Partially supported with funding from the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (Grant No: 4100081743).

References

- Tan CHH, Wilson S, McConigley R. Experiences of cancer patients in a patient navigation program: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:136-168.

- Tang KL, Kelly J, Sharma N, Ghali WA. Patient navigation programs in Alberta, Canada: an environmental scan. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E841-E847.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Wagner J, et al. Effectiveness of patient navigation to increase cancer screening in populations adversely affected by health disparities: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3026-3035.

- Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3539-3542.

- Ranaghan C, Boyle K, Meehan M, et al. Effectiveness of a patient navigator on patient satisfaction in adult patients in an ambulatory care setting: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:172-218.

- Dillon E, Kim P, Li M, et al. Breast cancer navigation: using physician and patient surveys to explore nurse navigator program experiences. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2021;25:579-586.

- Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113:1999-2010.

- Robinson-White S, Conroy B, Slavish K, Rosenzweig M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:127-140.

- Sunny A, Rustveld L. The role of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening completion and education: a review of the literature. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33:251-259.

- Garfield KM, Franklin EF, Battaglia TA, et al. Evaluating the sustainability of patient navigation programs in oncology by length of existence, funding, and payment model participation. Cancer. 2022;128(suppl 13):2578-2589.

- Ramsey S, Whitley E, Mears VW, et al. Evaluating the cost‐effectiveness of cancer patient navigation programs: conceptual and practical issues. Cancer. 2009;115:5394-5403.

- Kline RM, Rocque GB, Rohan EA, et al. Patient navigation in cancer: the business case to support clinical needs. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:585-590.

- Ahuja NA, Rodríguez-Colón SM, Costalas S, Lengerich EJ. Patient navigation and cancer-related care: policy solutions to improve access to Pennsylvania’s complex system of care. Journal of Cancer Policy. 2020;25:100231.

- Kelley L, Capp R, Carmona JF, et al. Patient navigation to reduce emergency department (ED) utilization among Medicaid insured, frequent ED users: a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:967-977.

- DeGroff A, Schroy PC III, Morrissey KG, et al. Patient navigation for colonoscopy completion: results of an RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:363-372.

- Li C, Liu Y, Xue D, Chan CWH. Effects of nurse-led interventions on early detection of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;110:103684.

- Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Ramos-Lopez WA, et al. Patient navigation to improve early access to supportive care for patients with advanced cancer in resource-limited settings: a randomized controlled trial. Oncologist. 2021;26:157-164.

- McKenney KM, Martinez NG, Yee LM. Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:280-286.

- Cervantes L, Hasnain-Wynia R, Steiner JF, et al. Patient navigation: addressing social challenges in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:121-129.

- Embick ER, Maeng DD, Juskiewicz I, et al. Demonstrated health care cost savings for women: findings from a community health worker intervention designed to address depression and unmet social needs. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24:85-92.

- Orme S, Zarkin GA, Dunlap LJ, et al. Cost and cost savings of navigation services to avoid rehospitalization for a comorbid substance use disorder population. Med Care. 2022;60:631-635.

- Graham P, Evitts T, Thomas-MacLean R. Environmental scans: how useful are they for primary care research? Can Fam Phys. 2008;54:1022-1023

- Charlton P, Doucet S, Azar R, et al. The use of the environmental scan in health services delivery research: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029805.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42:377-381.

- The Professional Oncology Navigation Task Force. Oncology navigation standards of professional practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2022;26:E14-E25.

- Lewis CM, Gamboa-Maldonado T, Belliard CJ, et al. Patient and community health worker perceptions of community health worker clinical integration. J Community Health. 2019;44:159-168.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Community Health Workers. 2023. www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes211094.htm

- National Association of Community Health Workers. Uniting for Health, Equity, and Social Justice. https://nachw.org/

- American Cancer Society. Workforce Development Task Group. Patient Navigation Job Roles By Levels Of Experience. American Cancer Society National Navigation Roundtable. 2023. https://navigationroundtable.org/wp-content/uploads/Workforce-Development-Job-Performance-Behaviors.pdf

- Pennsylvania Department of Health. Pennsylvania Cancer Coalition. 2023-2033 Pennsylvania Cancer Control Plan. 2023. www.pacancercoali tion.org/images/pdf/2023-2033_Pennsylvania_Cancer_Control_Plan.pdf

- Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A. Community cancer center administration and support for navigation services. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:141-148.

- Paskett ED, Battaglia T, Calhoun EA, et al. Isn’t there enough evidence on the benefits of patient navigation? CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:562-564.

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators. AONN+ Evidence-Based Navigation Metrics. https://aonnonline.org/navigation-metrics

- The Return on Investment of a Successful Navigation Program. Becoming Familiar with Business Performance Metrics as a Method to Evaluate Navigation Services. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2022;13(8):248-250.

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+). Local Navigator Networks. https://aonnonline.org/local-navigator-networks