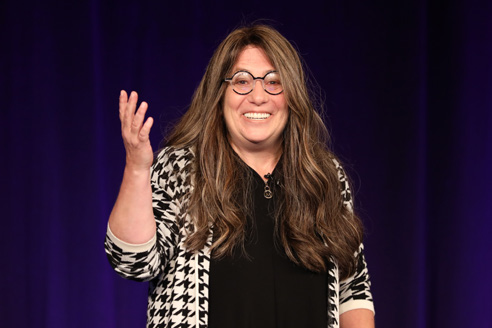

Gail Zahtz, Founder and CEO of WiseCare Health

As a survivor of homelessness, domestic abuse, and advanced-stage breast cancer, Gail Zahtz is no stranger to hardship. When things got so bad that she was told to simply “accept her situation,” she credits her navigator with saving her life by helping her find her own voice. Now, she uses that voice to be a passionate advocate for changing the minds of administrators and payers who think of navigation as a nonessential extra cost in the already expensive world of oncology.

During treatment, she said, her navigator took her hand and walked with her through her cancer. “The ‘walking’ that navigators do on a moment-by-moment basis could be the most important thing that is done for an oncology patient,” she said. “Because of my navigator, I knew I was not alone. But while my amazing experience is not the experience of most patients, it can be.”

At the AONN+ 13th Annual Navigation & Survivorship Conference in New Orleans, Ms Zahtz, a value-based healthcare transformation expert and founder and CEO of WiseCare Health, shared her inspiring story and described what kept her going during her worst days.

Standing Her Ground

Nearly 7 years ago, as a single mother with 4 kids living in Minnesota, Ms Zahtz was getting more and more sick. After reaching the point where she could no longer walk or take care of herself, she knew it was time to go to the hospital. And after being told she was too sick to go home, she was informed that she would be moved to a nearby “facility.”

“I looked at this facility and said, ‘there’s no rehab, there’s no treatment, there’s nothing in this facility. This looks an awful lot like hospice,’” she said. “These are facilities of no hope, where we warehouse people when we have nowhere else to put them.”

She told them she was not going, so they brought in security. “And I told them again I’m not going,” she recalls. Then, they brought in a psychiatrist. “He talked to me for an hour and said I could do things like make videos and write letters to leave for my kids; he told me I just needed to accept it,” she said. “But I told him, ‘I’m not accepting this.’”

After 6 days, she was transferred to the basement of a one-star skilled nursing facility. “There was mold coming down from the ceiling,” she remembers. “I was warehoused, and 20 years younger than the youngest resident there.”

It was then she realized that she had to find her voice. Because at that point, no one was trying to find an answer to what was making her so sick; it seemed everyone had given up on her. She remembered asking her doctor for a mammogram several years prior, but being told she was too young. After conducting a self-exam in the nursing home, she was then referred by a primary care doctor for a mammogram and bilateral biopsies.

After being sent back to the nursing home, she received a call telling her she had been scheduled for a visit with the next available oncologist.

“I said, ‘Oncologist? You mean I have cancer?’ And that’s how I got my diagnosis,” she stated.

Meeting the Care Team

After her diagnosis of advanced ductal carcinoma, Ms Zahtz’s experience began to change. She was assigned a palliative team at the University of Minnesota, where on her first day she met with physicians, nurses, nurse advocates, nurse navigators, and social workers.

“I met with all 6 of them at the same time and said, ‘here’s the deal: I need you to write in those notes that I’m going to survive.’”

She started chemotherapy treatments, eventually leading up to doxorubicin, aka “The Red Devil.”

“At that point I was on the floor,” she recalled. “They asked me if I wanted to stop, but I said I promised my son I’d finish it.”

Meeting Her Navigator

“I came from domestic violence, so I was totally alone,” she said. “I had gone from state to state with 4 children from 9 to 18 years old.”

She remembers seeing 2 chairs at every visit to her oncologist—one for the patient and one for the caregiver—which only exacerbated her feelings of loneliness. But her navigator, Kathy Hodges, filled that empty chair and got her through the darkest days of treatment.

“But what I didn’t know at the time is that millions of oncology patients around the globe have it much, much harder than I had it, because they don’t have a Kathy Hodges,” she said.

Because of her navigator, Ms Zahtz did not have to worry about things like care coordination or transportation. “It was unbelievable that I didn’t have to worry about how I was going to get to my appointments,” she said.

After completing The Red Devil, her tumors were right on the brink of being small enough for surgical removal, and one surgeon was willing to take the risk.

Finding Her Voice Through the Trauma

“All in, I had 50 surgeries,” she said. “But after 50 surgeries and all of my other treatments, my stomach did not close.”

Her stomach eventually closed up after 6 months, but then she lost all of her teeth. “This was probably the most traumatic thing for me,” she said. She added that other types of reconstruction postsurgery are covered by insurance, but the mouth is not, highlighting an important area in which navigators can advocate for patients.

Between all of the trauma and the constant painkillers, she remembers struggling to find her voice. “It felt like there was a black wall between me and everybody else, especially the doctors,” she said. “So, I relied on my navigators to help me find my voice so that I could advocate for myself. I was able to do that because I had such a good navigation team.”

Ms Zahtz has had no evidence of disease for nearly 6 years. She has now seen 2 of her children get married, is sending 1 off for a year abroad, is watching another wrap up high school, and has become a grandmother.

“I got to see all of that—everything they said that I would not see because I had to accept my situation—because I found my voice and because I had navigators,” she said.

Once she found her voice, she began using it to help others. According to Ms Zahtz, this became a mission for her while she was still in the hospital. She got tired of being on all the drugs and anesthesia and started refusing them when she could. As a result, she began talking more and more.

“I’d found my purpose—I had 4 children and a reason to be here—and purpose is the magic that gets us through the unthinkable,” she said. “So, I just started talking about healthcare and what we could do differently.”

One day she looked up during a port removal to see 15 doctors in the room. Asking them what they were doing there, they replied: “We hear you give talks. Do you take requests?”

“So, I laid there for an hour talking about fall prevention while I was cut open,” she said. “I gave an hour talk from my bed, because I had purpose.”

The Importance of Value-Based Care

Although she credits her experience with navigation for saving her life, she realizes that most patients with cancer do not have the “luxury” of a navigator. She emphasizes the importance of shifting from a fee-for-service to a value-based healthcare model that addresses health equity issues and drives home the value of navigation.

“Fee-for-service says doctors get paid when somebody falls and breaks their arm on the sidewalk, so they keep the sidewalks broken,” she said. “Value-based care says, providers get paid whether patients are sick or well, so let’s fix the sidewalk so nobody breaks their arm.”

According to Ms Zahtz, navigation goes hand in hand with value-based care because it utilizes a team approach.

“Navigators work. It has been proven that when you work side-by-side with patients, they don’t always want the most expensive care,” she said, adding that cost-related issues often have nothing to do with care; rather, they are attributed to factors like patients needing x-rays or MRIs redone because they were not connected to the correct electronic medical record.

“These are things that navigators can’t control,” she added. “But my teams and I are working toward helping those in the business of healthcare to control them, so we can lower the cost of care and improve the patient experience.”