I. Executive Summary

Research articles related to endometrial and ovarian cancer patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being published in the past 5 years were analyzed to provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative education tool to empower patients and their caregivers following endometrial and ovarian cancer diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

A total of 5962 articles were screened, 758 full-text publications were reviewed, and 92 relevant articles were identified. The results of the analysis are described in detail below.

II. Overview of Gap Analysis

Literature Overview

We performed a comprehensive search of the published scientific literature for physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients diagnosed with endometrial and ovarian cancer and their caregivers in the past 5 years (2018–2023). An overview of the methodology utilized for the specific end points is provided in detail below.

Methods

PubMed Database Searches

To identify published review articles relevant to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients diagnosed with endometrial and ovarian cancer and their caregivers, the PubMed database was searched using the following parameters:

- Articles published between January 1, 2018, and May 1, 2023

- Articles were limited to studies focused on or conducted in humans

- Specific search terms were conducted as follows:

- Physical well-being

- subtype, risk reduction, hormone therapy, weight, pathology, diagnostics, imaging, biopsy, staging, mutations, genetic counseling, advanced presentation, surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation, neoadjuvant, side effect, cognition, nutrition, physical activity, exercise, functional health, self-care, pain, palliative care, symptom management, survivorship, end of life, hospice, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, caregiver

- Psychological well-being

- shared decision-making, social worker, family, preparedness, resilience, loss of control, mental health, body image, suicide screening, depression screening, distress screening, decision-making capacity, motivation, problem-solving skills, coping, stress management, anxiety, schizophrenia, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, caregiver

- Social well-being

- support, advocacy, network, culture, family support, community support, relationship, communication, intimacy, sexuality, employment, financial toxicity, barriers to care, childcare, transportation, education, health literacy, learning style, communication with multidisciplinary team, communication with family, communication with caregivers, communication with children, survivorship, chronic disease, surveillance plan, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, caregiver

- Spiritual well-being

- religiosity, spiritual distress, meaning and purpose, uncertainty, hope, peace, life satisfaction, life fulfillment, legacy building, spiritual well-being, mindfulness relaxation, yoga, meditation, creative arts, writing, drawing, photography, music therapy, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, caregiver

Categorization

Publications were categorized based on the following parameters:

- Publication type

- Research articles

- Review articles

- Domain

- Physical

- Psychological

- Social

- Spiritual

- Conclusion of benefit

- Positive, negative, or indeterminate

Analyses

The following analyses were conducted:

- Publications by year

- Publications by year and domain

III. Publications Overview: Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer Patient and Caregiver Education

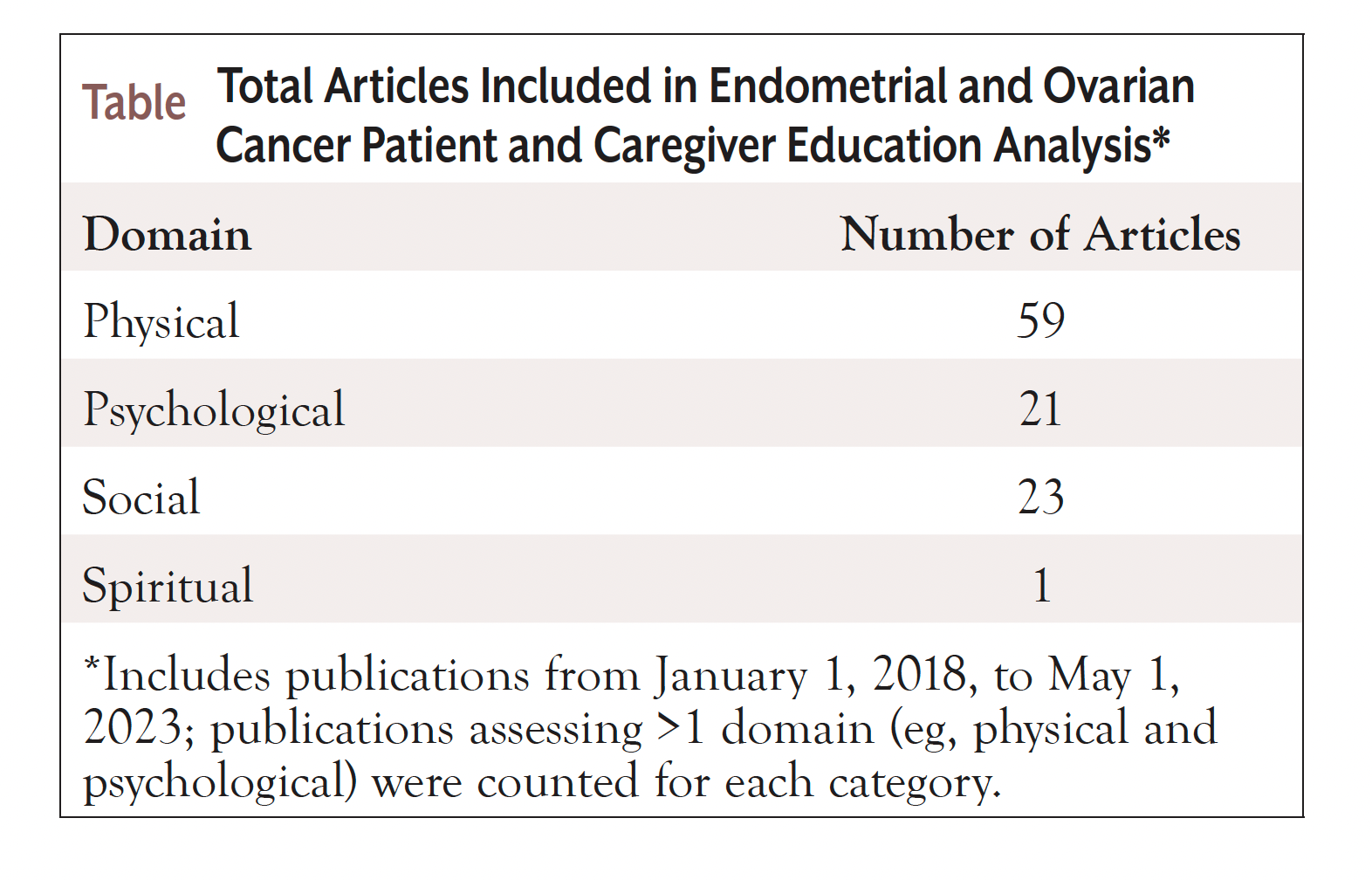

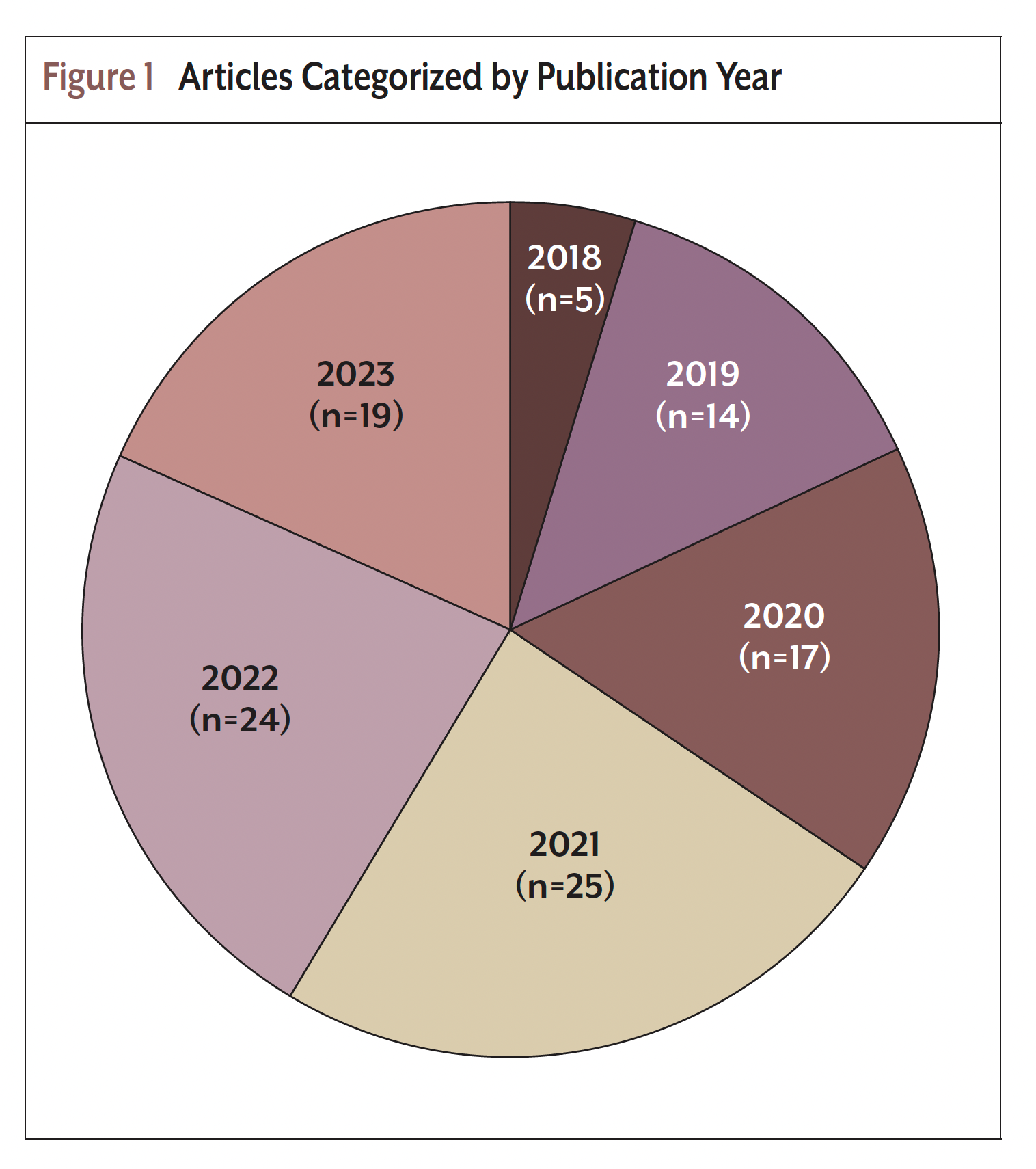

A total of 758 articles met the search criteria and limits described above. After thoroughly screening all titles and full texts for relevance, 92 applicable articles were identified and included in the gap analysis (Table), with the largest number published in 2021 (n=25) and the lowest number published in 2018 (n=5; Figure 1).

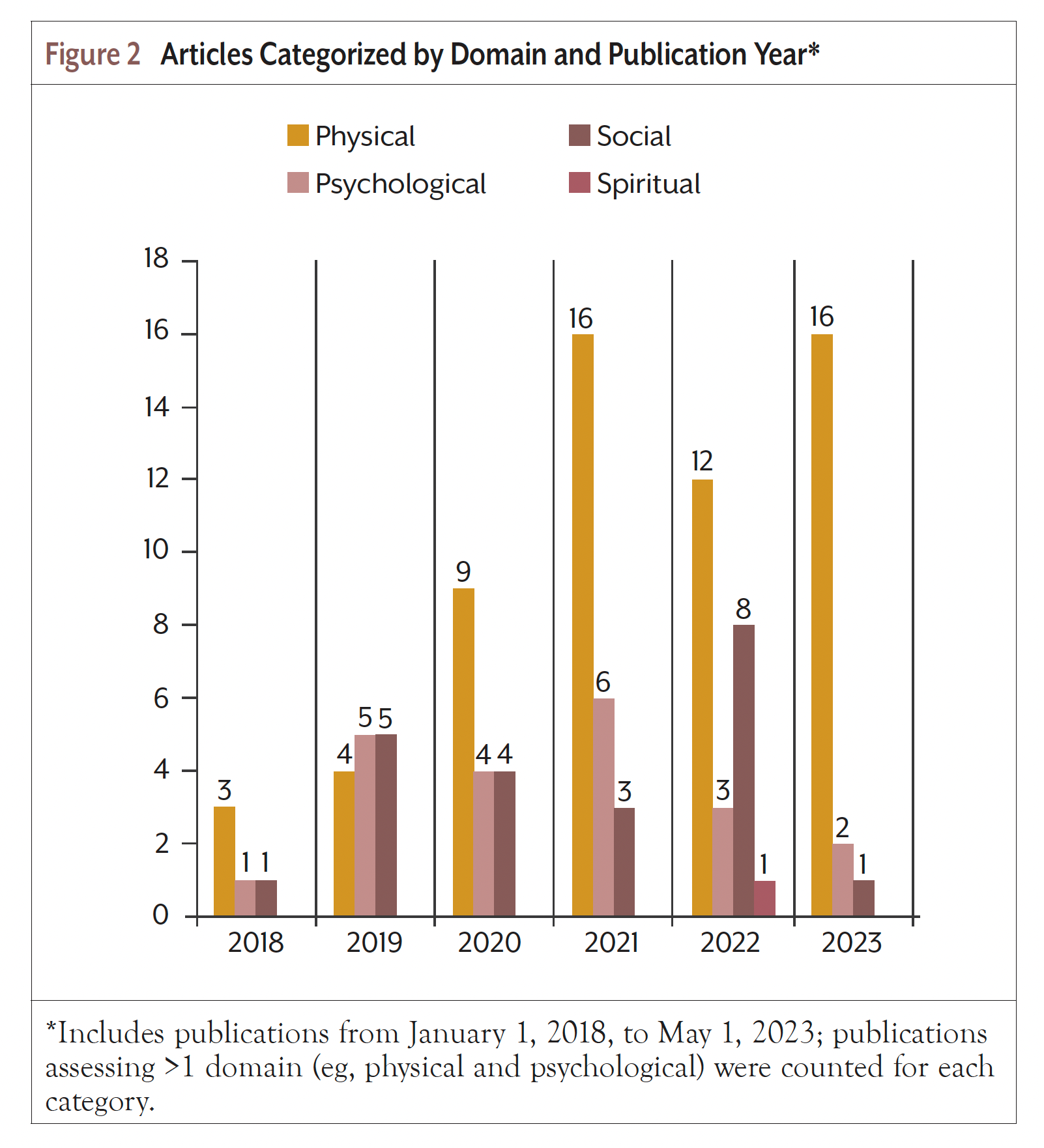

Publications categorized by domain and publication year are tallied in Figure 2. Publications that assessed more than 1 domain were included for each category. The majority of articles focused on the physical domain (n=59), followed by social (n=23), psychological (n=21), and spiritual domains (n=1).

The following section provides a detailed discussion of each analysis categorized by domain.

IV. Overview of Publications by Domain

Physical

We identified 59 articles evaluating the physical domain for patients with endometrial and ovarian cancer and their caregivers.1-59 Of these articles, 25 discussed treatment, 13 discussed exercise and nutrition, and 12 discussed biopsy, imaging, and screening. The largest number of articles was published in 2021 and 2023 (n=16 each), followed by 2022 (n=12), 2020 (n=9), 2019 (n=4) and 2018 (n=3). Two articles spanned the physical and psychological domains; 2 the physical and social domains; 1 the physical, psychological, and social domains; and 1 the physical, social, and spiritual domains.

Among survivors of endometrial cancer, 61% reported poor sleep quality, and 81% reported decreased quality of life.2

Home-based muscle strengthening exercise is feasible and recommended in endometrial cancer survivors.21 Physical activity has been associated with decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer.56 Limited available evidence suggests that there are few to no serious or life- threatening adverse effects associated with weight loss interventions in addition to standard management in women with endometrial cancer who are obese or overweight.1 Endometrial cancer survivors have experienced favorable and clinically relevant improvements in functional fitness with home-based exercise intervention.22 Ketogenic diets have also been investigated in women with endometrial and ovarian cancer, with no adverse effects on blood lipids.7 Among patients with endometrial and ovarian cancer, a ketogenic diet may lead to improved physical function, increased energy, and decreased food cravings without negatively impacting quality of life.8 Mediterranean, plant-based, and ketogenic diets have been associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer, whereas increased body mass index has been associated with a higher risk of endometrial cancer.55 Nutrient deficiencies have been associated with endometrial and ovarian cancer.6

The optimal time interval between diagnosis and surgical treatment of endometrial cancer is 8 weeks or less, and the interval between surgery and adjuvant therapy is a maximum of 9 weeks.45 Ultraminimally invasive surgical techniques have been shown to be feasible and safe in patients with endometrial cancer.29 The laparoscopic hysterectomy approach yields surgical outcomes and similar survival rates as open surgery in patients with early endometrial cancer.20 Minimally invasive surgery has been shown to have no negative impact on the prognosis of patients with high-risk endometrial cancer histology.27 Fertility-sparing surgery in early-stage endometrial cancer has been associated with a positive response to therapy, with a good chance of pregnancy and live birth.12 Fertility-sparing surgery in endometrial and ovarian cancer has also been associated with acceptable progression-free and overall survival rates.28 Among patients with advanced endometrial cancer, a significant proportion undergoing primary cytoreductive surgery are left with residual disease, which has been associated with poor survival outcomes.3 Radiation therapy guidelines have been provided, outlining indications for adjuvant therapy, techniques, and indications for systemic therapy.23 Whole abdominal radiotherapy is no longer standard of practice, and modern techniques are emerging in both the palliative and salvage settings.14 Data can be used to drive decision for surgical management and postoperative therapy in endometrial carcinoma.17 In ovarian cancer, nintedanib added to chemotherapy leads to increased toxicity and reduced chemotherapy efficacy.16 Treatment options for rare endometrial cancers have expanded based on molecular profiling leading to personalized, actionable targets.9 In endometrial cancer, FDA-approved immunotherapy includes pembrolizumab and dostarlimab.18 Dostarlimab is effective in recurrent or advanced endometrial cancer, particularly microsatellite instability-hypermutated/DNA mismatch repair-deficient disease.26 Previously, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in ovarian cancer failed to improve clinical outcomes.34 There are several potential strategies using an immunotherapy-based combination approach that may combat resistance or enhance the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer.36 Results from a phase 2 study of patients with endometrial cancer revealed that treatment with pembrolizumab, radiotherapy, and an immunomodulatory 5-drug cocktail had durable but modest antitumor activity and acceptable toxicity.11 Systemic or topical menopausal hormone therapy has not been associated with harm and does not decrease survival among women with nonserous epithelial ovarian cancer.46

Barriers to palliative care implementation among women with advanced ovarian cancer include confusion with hospice and prognostication challenges.40 It has been proposed that early palliative care be considered routinely upon recurrence or progression based on patients’ acceptance and symptom burden of a pilot randomized controlled trial.10 Adverse reaction guidance has been provided for women with endometrial cancer receiving combination therapy with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab.38 Regarding end-of-life symptom management in patients with ovarian cancer, physicians tend to use more invasive care in younger patients, although it does not prolong survival.54

Endometrial cancer can be classified molecularly, with actionable opportunities based on this classification.24 Treatments and targets in endometrial cancer can be assessed by molecular subtype.25 Adjuvant therapy options for endometrial cancer have been developed and evaluated based on a molecularly integrated risk profile.57 In ovarian cancer, the rates of microsatellite instability-high, mismatch repair deficiency, and mismatch repair germline mutations are highest in nonserous, nonmucinous, and endometrioid subtypes.41 PIK3CA mutations have been shown to exert a negative impact on survival of patients with endometrial cancer.4 Clinical outcomes for patients with endometrial cancer with POLE mutations have not been associated with traditional risk factors, and furthermore, these patients do not seem to experience benefit with adjuvant therapy.39 Pathogenic variants in several genes have been identified in 20% to 25% of patients with ovarian cancer, with most encoding proteins involved in DNA mismatch repair pathways.50

Risk of lymph node metastasis in endometrial cancer is associated with cervical invasion, lymphopoiesis space invasion, and ovarian metastasis.30 Bisphosphonates, particularly those that contain nitrogen, have been associated with significant risk reduction of endometrial cancer.31 Although bisphosphonate use has been associated with reduced risk of endometrial cancer, this is not the case for ovarian cancer.59 There is a need for risk prediction models to identify women at particularly high risk of endometrial cancer who may benefit from risk-reducing interventions.44

Endometrial biopsy has 90% sensitivity for endometrial cancer, although it may result in insufficient tissue or false-negative results.33 The value of liquid biopsy has been investigated in endometrial cancer screening, diagnosis, response to treatment, and monitoring of prognosis.51 The diagnostic test accuracy for sentinel lymph node biopsy is thought to be good, with high sensitivity.43 Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer is safe and accurate in both high- and low-risk settings.53 Currently, there is limited evidence available to support screening for endometrial and ovarian cancer among women with Lynch syndrome.32 Imaging has a key role in diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of endometrial cancer.48 In endometrial cancer, there are roles for MRI-guided radiation therapy, advanced MRI techniques, and hybrid PET/MRI.37 PET tracers can be used to evaluate endometrial and ovarian cancers.19 For diagnosing endometrial cancer, 3-dimensional ultrasound can be used to investigate and predict outcomes based on endometrial volume and vascular indices.58 Preoperative staging of endometrial cancer includes computed tomography, transvaginal ultrasound, and MRI.15 For managing endometrial cancer, molecular characterization, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system, and guideline-based imaging should be

It is known that 1 in 3 women attending hospital-based follow-up report unmet needs, highlighting the need for alternative follow-up models. Approximately 50% of patients with ovarian cancer screened positive for moderate/severe distress.

Psychological

We identified 21 articles evaluating the psychological domain.5,47,49,60-77 Of these articles, 6 discussed education and communication, 4 discussed sexuality, and 4 discussed survivorship and follow-up. Six articles were published in 2021, 5 in 2019, 4 in 2020, 3 in 2022, 2 in 2023, and 1 article was identified for 2018. Overall, 4 articles spanned the psychological and social domains.

Following an intervention focused on education, coping, and support, anxiety scores were significantly lower in women with endometrial cancer compared with levels prior to the intervention.71

Among women with endometrial and ovarian cancer, nurse-led follow-up resulted in higher emotional and cognitive functioning and can be considered an effective substitute for hospital-based follow-up.70 It is known that 1 in 3 women attending hospital-based follow-up report unmet needs, highlighting the need for alternative follow-up models.66 Approximately 50% of patients with ovarian cancer screened positive for moderate/severe distress.76

Regarding the preference for chemoradiotherapy over radiotherapy for high-risk endometrial cancer, older patients with comorbidity had lower preference, whereas patients with enhanced numeracy skills and chemoradiotherapy history had a higher preference for chemoradiotherapy.74 Furthermore, patients needed higher benefits than clinicians to prefer chemoradiotherapy, emphasizing the importance of shared decision-making. The use of a priorities assessment tool in ovarian cancer was associated with improved identification of current goals and priorities, and an increased level of comfort participating in shared decision-making with the medical team.63 Referral to genetic counseling at the time of ovarian cancer diagnosis leads to high uptake without a long-term psychologic toll, demonstrating that clinicians should not cite concern about additional emotional distress as a reason not to refer.64

Approximately 1 in 8 women had a prescription for psychotropic medications prior to surgery for early-stage endometrial cancer, with few receiving a new prescription following surgery.75 Overall prescription rates were not different from other patients with cancer but were higher than those reported in the general population. Increased risk of mental illness was observed among survivors of ovarian cancer within 5 years after cancer diagnosis, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary monitoring and treatment.65 A hypothetical patient case describing a patient with end-stage ovarian cancer with a desire to commit suicide has been used to illustrate issues about patient autonomy, confidentiality, and nursing code of ethics and beneficence.68 Patients with ovarian cancer who receive high-quality nursing care have reported increased levels of anxiety relief and decreased depression during the perioperative period.67

A web-based intervention designed to improve advanced care planning in women with ovarian cancer resulted in lower distress, lower depression, and reduced distress while incorporating patient preferences.

Online survey results from women with ovarian cancer demonstrate that women question self-worth, relationships, and societal placement as a result of changes in bodily functioning, fertility, and sexuality.61 Patients with ovarian cancer have been shown to experience reduced sexual function and quality of life following diagnosis, highlighting the need for counseling.62

Endometrial cancer survivors participating in a telephone-based physical activity intervention experienced positive improvements in general health, pain, and somatic distress, but not in other aspects of quality of life.47 A home-based trial of exercise led to significantly reduced depressive symptomatology compared with attention-control in survivors of ovarian cancer.5 Reduction of symptom burden via an auricular acupressure intervention in patients with ovarian cancer led to improved sleep quality in family caregivers.77

Social

We identified 23 articles evaluating the social domain.13,42,49,52,60,69,72,73,78-92 Of these articles, 8 focused on communication and support, 5 discussed survivorship and outcomes, 1 discussed cognition, and 3 each discussed financial toxicity, sexuality, and barriers to care. Eight articles were published in 2022, 6 in 2019, 4 in 2020, 3 in 2021, and 1 article each was identified for 2018 and 2023.

Patient experiences with endometrial cancer revealed that patients and providers lack knowledge on symptoms and risk factors, and patients with morbid obesity are subjected to stigma and poor communication in the healthcare system.81 Currently, there is an absence of evidence to determine the effectiveness of health education initiatives to promote early presentation and referral for women with symptoms of endometrial cancer.79 Studies examining the psychosocial impact of the decision-making process related to undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy surgery are scarce and often lack clear theoretical frameworks.60 Pregenetic testing communication increases knowledge without increasing anxiety for most patients, and many patients report that communication via methods other than face-to-face counseling are acceptable.85 Adolescents and young adult children of mothers who underwent previous BRCA testing recalled conversations and had muted, multifaceted, and wide-ranging psychosocial impacts.91 Most children reported that they would consider genetic testing for themselves, although often later in life.

Women with ovarian cancer reported an impact of self-perceived burden and social network diversity of psychological distress via loneliness.84 Patients with ovarian cancer and their caregivers primarily used online health communities for finding knowledge related to low- to medium-level learning objectives, suggesting that these communities are promising resources for obtaining knowledge related to ovarian cancer.80 Women with ovarian cancer described a targeted social media campaign as helpful/meaningful and were likely to engage if the campaign featured stories relevant to their personal experiences.83 In women with ovarian cancer, a mobile application intervention led to improved use of genetic counseling services, greater knowledge about hereditary cancer, improved self-efficacy, and greater communication with family members.92

During follow-up of ovarian cancer survivors, no studies have examined the proactive use of patient-reported outcome measures, highlighting the need for investigation as to whether these measures may facilitate an individualized and effective program based on needs and preferences.86 A web-based intervention designed to improve advanced care planning in women with ovarian cancer resulted in lower distress, lower depression, and reduced distress while incorporating patient preferences.72 To provide high-quality care for patients with ovarian cancer, core components include care coordination and patient education, prevention and screening, diagnosis and initial management, treatment planning, disease surveillance, equity in care, and quality of life.90 Survivorship care plans may be beneficial for patients with endometrial and ovarian cancer who want information about their disease, but they may be less beneficial for those who avoid medical information.82

Among women with ovarian cancer, primary barriers to participation in physical activity include disease- or treatment-related side effects, fear of falling or injury, and the absence of counseling.42 Enabling components to participation in physical activity include individualized interventions with goals and support from medical and health professionals. A pilot study designed to increase physical activity among survivors of ovarian cancer by leveraging principles of social support, behavioral economics, and gamification demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy.49 Among women with ovarian cancer, exercise interventions led to improved quality of life and survival, as well as general symptom burden.52

Among endometrial cancer survivors, positive effects of obesity on vaginal and sexual symptoms have been reported.88 Up to 75% of women with ovarian cancer have reported adverse changes in their sex lives following the diagnosis, with sexually active women reporting pain and vaginal dryness.69 Among women with ovarian cancer, there is an increased prevalence of urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction, with some reporting loss of desire and poorer sexual function scores.73

During gynecologic cancer treatment, 50% of insured women experience financial toxicity, with possible higher costs among Medicare enrollees.78 Treatment options for ovarian cancer have led to variable patient costs, and these patients have unique risk factors for high financial toxicity.89 Prompt identification and intervention may help alleviate financial distress associated with ovarian cancer care. Fiscal costs of dose and schedule of radiopharmaceuticals and social costs based on individual productivity loss or asset expenditure have been reported as primary financial toxicities.87

Spiritual

Only 1 article was identified that evaluated the spiritual domain, and it also spanned the physical and social domains.13 This study demonstrated that restorative and vigorous yoga practice led to improved overall and fluid cognitive function.

V. Summary

Summary of Key Points

- A total of 92 applicable articles were identified, of which 16 articles were published in 2023

- Overall, 59 articles evaluated endometrial and ovarian cancer patient/caregiver physical well-being, 21 evaluated psychological well-being, 23 evaluated social well-being, and 1 article discussed spiritual well-being

- Several review articles and clinical trials discuss treatment algorithms and consideration for treatment of patients with endometrial and ovarian cancer

- 10 articles evaluated multiple domains

- 2 articles focused on caregivers

References

- Agnew H, Kitson S, Crosbie EJ. Interventions for weight reduction in obesity to improve survival in women with endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD012513.

- Alanazi MT, Alanazi NT, Alfadeel MA, Bugis BA. Sleep deprivation and quality of life among uterine cancer survivors: systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:2891-2900.

- Albright BB, Monuszko KA, Kaplan SJ, et al. Primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced stage endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:237.e1-237.e24.

- Bredin HK, Krakstad C, Hoivik EA. PIK3CA mutations and their impact on survival outcomes of patients with endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0283203.

- Cartmel B, Hughes M, Ercolano EA, et al. Randomized trial of exercise on depressive symptomatology and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in ovarian cancer survivors: the Women’s Activity and Lifestyle Study in Connecticut (WALC). Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:587-594.

- Ciebiera M, Esfandyari S, Siblini H, et al. Nutrition in gynecological diseases: current perspectives. Nutrients. 2021;13:1178.

- Cohen CW, Fontaine KR, Arend RC, Gower BA. A ketogenic diet is acceptable in women with ovarian and endometrial cancer and has no adverse effects on blood lipids: a randomized, controlled trial. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72:584-594.

- Cohen CW, Fontaine KR, Arend RC, et al. Favorable effects of a ketogenic diet on physical function, perceived energy, and food cravings in women with ovarian or endometrial cancer: a randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients. 2018;10:1187.

- Crane E. Beyond serous: treatment options for rare endometrial cancers. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022;23:1590-1600.

- Cusimano MC, Sajewycz K, Harle I, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of early palliative care among women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021;43:707-715.

- De Jaeghere EA, Tuyaerts S, Van Nuffel AMT, et al. Pembrolizumab, radiotherapy, and an immunomodulatory five-drug cocktail in pretreated patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical or endometrial carcinoma: results of the phase II PRIMMO study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72:475-491.

- De Rocco S, Buca D, Oronzii L, et al. Reproductive and pregnancy outcomes of fertility-sparing treatments for early-stage endometrial cancer or atypical hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;273:90-97.

- Deng G, Bao T, Ryan EL, et al. Effects of vigorous versus restorative yoga practice on objective cognition functions in sedentary breast and ovarian cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221089221.

- Durno K, Powell ME. The role of radiotherapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:366-371.

- Faria SC, Devine CE, Rao B, et al. Imaging and staging of endometrial cancer. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2019;40:287-294.

- Ferron G, De Rauglaudre G, Becourt S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without nintedanib for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: lessons from the GINECO double-blind randomized phase II CHIVA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;170:186-194.

- Filippova OT, Leitao MM. The current clinical approach to newly diagnosed uterine cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2020;20:581-590.

- Fontenot VE, Tewari K. The current status of immunotherapy in the treatment of primary advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2023;35:34-42.

- Friedman SN, Itani M, Dehdashti F. PET imaging for gynecologic malignancies. Radiol Clin North Am. 2021;59:813-833.

- Gitas G, Pados G, Laganà AS, et al. Role of laparoscopic hysterectomy in cervical and endometrial cancer: a narrative review. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2023;32:1-11.

- Gorzelitz J, Costanzo E, Gangnon R, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of home-based strength training in endometrial cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17:120-129.

- Gorzelitz JS, Stoller S, Costanzo E, et al. Improvements in strength and agility measures of functional fitness following a telehealth-delivered home-based exercise intervention in endometrial cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:447-455.

- Harkenrider MM, Abu-Rustum N, Albuquerque K, et al. Radiation therapy for endometrial cancer: an American Society for Radiation Oncology clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2023;13:41-65.

- Jamieson A, McAlpine JN. Molecular profiling of endometrial cancer from TCGA to clinical practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:210-216.

- Karpel H, Slomovitz B, Coleman RL, Pothuri B. Biomarker-driven therapy in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33:343-350.

- Kasherman L, Ahrari S, Lheureux S. Dostarlimab in the treatment of recurrent or primary advanced endometrial cancer. Future Oncol. 2021;17:877-892.

- Kim NR, Lee AJ, Yang EJ, et al. Minimally invasive surgery versus open surgery in high-risk histologic endometrial cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;166:236-244.

- Kohn JR, Katebi Kashi P, Acosta-Torres S, et al. Fertility-sparing surgery for patients with cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:392-402.

- La Russa M, Liakou C, Burbos N. Ultra-minimally invasive approaches for endometrial cancer treatment: review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2021;112:31-46.

- Li M, Wu S, Xie Y, et al. Cervical invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, and ovarian metastasis as predictors of lymph node metastasis and poor outcome on stages I to III endometrial cancers: a single-center retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:193.

- Li YY, Gao LJ, Zhang YX, et al. Bisphosphonates and risk of cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:1570-1581.

- Lim N, Hickey M, Young GP, et al. Screening and risk reducing surgery for endometrial or ovarian cancers in Lynch syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:646-655.

- Long S. Endometrial biopsy: indications and technique. Prim Care. 2021;48:555-567.

- Lorusso D, Ceni V, Muratore M, et al. Emerging role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2020;25:445-453.

- Luna C, Balcacer P, Castillo P, et al. Endometrial cancer from early to advanced-stage disease: an update for radiologists. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:5325-5336.

- Mahdi H, Chelariu-Raicu A, Slomovitz BM. Immunotherapy in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33:351-357.

- Maheshwari E, Nougaret S, Stein EB, et al. Update on MRI in evaluation and treatment of endometrial cancer. Radiographics. 2022;42:2112-2130.

- Makker V, Taylor MH, Oaknin A, et al. Characterization and management of adverse reactions in patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma treated with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab. Oncologist. 2021;26:e1599-e1608.

- McAlpine JN, Chiu DS, Nout RA, et al. Evaluation of treatment effects in patients with endometrial cancer and POLE mutations: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Cancer. 2021;127:2409-2422.

- Miller D, Nevadunsky N. Palliative care and symptom management for women with advanced ovarian cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018; 32:1087-1102.

- Mitric C, Salman L, Abrahamyan L, et al. Mismatch-repair deficiency, microsatellite instability, and lynch syndrome in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;170:133-142.

- Morrison KS, Paterson C, Coltman CE, Toohey K. What are the barriers and enablers to physical activity participation in women with ovarian cancer? A rapid review of the literature. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36:151069.

- Nagar H, Wietek N, Goodall RJ, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for diagnosis of lymph node involvement in endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;6:CD013021.

- Njoku K, Abiola J, Russell J, Crosbie EJ. Endometrial cancer prevention in high-risk women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;65:66-78.

- Pergialiotis V, Haidopoulos D, Tzortzis AS, et al. The impact of waiting intervals on survival outcomes of patients with endometrial cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;246:1-6.

- Rees M, Angioli R, Coleman RL, et al. European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) and International Gynecologic Cancer Society (IGCS) position statement on managing the menopause after gynecological cancer: focus on menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2020;134:56-61.

- Robertson MC, Lyons EJ, Song J, et al. Change in physical activity and quality of life in endometrial cancer survivors receiving a physical activity intervention. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:91.

- Saleh M, Virarkar M, Bhosale P, et al. Endometrial cancer, the current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system, and the role of imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2020;44:714-729.

- Schrier E, Xiong N, Thompson E, et al. Stepping into survivorship pilot study: harnessing mobile health and principles of behavioral economics to increase physical activity in ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2021; 161:581-586.

- Shah S, Cheung A, Kutka M, et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer: providing evidence of predisposition genes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:8113.

- Shen Y, Shi R, Zhao R, Wang H. Clinical application of liquid biopsy in endometrial carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2023;40:92.

- Sicardo Jiménez S, Vinolo-Gil MJ, Carmona-Barrientos I, et al. The influence of therapeutic exercise on survival and the quality of life in survivorship of women with ovarian cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19:16196.

- Stämpfli CAL, Papadia A, Mueller MD. From systematic lymphadenectomy to sentinel lymph node mapping: a review on transitions and current practices in endometrial cancer staging. Chin Clin Oncol. 2021;10:22.

- Tal O, Ben Shem E, Peled O, et al. Age disparities in end of life symptom management among patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Palliat Care. 2023;38:184-191.

- Thrastardottir TO, Copeland VJ, Constantinou C. The association between nutrition, obesity, inflammation, and endometrial cancer: a scoping review. Curr Nutr Rep. 2023;12:98-121.

- Tucker K, Staley SA, Clark LH, Soper JT. Physical activity: impact on survival in gynecologic cancer. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74:679-692.

- van den Heerik ASVM, Horeweg N, de Boer SM, et al. Adjuvant therapy for endometrial cancer in the era of molecular classification: radiotherapy, chemoradiation and novel targets for therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:594-604.

- Xydias EM, Kalantzi S, Tsakos E, et al. Comparison of 3D ultrasound, 2D ultrasound and 3D Doppler in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma in patients with uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;277:42-52.

- Zhang XS, Zhang YM, Li B, et al. Risk reduction of endometrial and ovarian cancer after bisphosphonates use: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150:509-514.

- Alves-Nogueira AC, Melo D, Carona C, Figueiredo-Dias M. The psychosocial impact of the decision to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy surgery in BRCA mutation carriers and the role of physician-patient communication. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:2429-2440.

- Boding SA, Russell H, Knoetze R, et al. ‘Sometimes I can’t look in the mirror’: recognising the importance of the sociocultural context in patient experiences of sexuality, relationships and body image after ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31:e13645.

- Cianci S, Tarascio M, Rosati A, et al. Sexual function and quality of life of patients affected by ovarian cancer. Minerva Med. 2019;110:320-329.

- Frey MK, Ellis A, Shyne S, et al. Bridging the gap: a priorities assessment tool to support shared decision making, maximize appointment time, and increase patient satisfaction in women with ovarian cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:e148-e154.

- Frey MK, Lee SS, Gerber D, et al. Facilitated referral pathway for genetic testing at the time of ovarian cancer diagnosis: uptake of genetic counseling and testing and impact on patient-reported stress, anxiety and depression. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:280-286.

- Hu S, Baraghoshi D, Chang CP, et al. Mental health disorders among ovarian cancer survivors in a population-based cohort. Cancer Med. 2023;12: 1801-1812.

- Jeppesen MM, Mogensen O, Hansen DG, et al. How do we follow up patients with endometrial cancer? Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21:57.

- Jin P, Sun LL, Li BX, et al. High-quality nursing care on psychological disorder in ovarian cancer during perioperative period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29849.

- Kusheba J, Mulvihill K. A patient’s suicidal ideations and a clinical nurse leader’s responsibility. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2018;20:512-518.

- Logue CA, Pugh J, Jayson G. Psychosexual morbidity in women with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:1983-1989.

- Ngu SF, Wei N, Li J, et al. Nurse-led follow-up in survivorship care of gynaecological malignancies—a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29:e13325.

- Niroomand S, Youseflu S, Gilani MM, et al. Does educational-supportive program affect anxiety in women with endometrial cancer? Result from a randomized clinical trial. Indian J Cancer. 2021;58:336-341.

- Petzel SV, Isaksson Vogel R, Cragg J, et al. Effects of web-based instruction and patient preferences on patient-reported outcomes and learning for women with advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2018;36:503-519.

- Pizzoferrato AC, Klein M, Fauvet R, et al. Pelvic floor disorders and sexuality in women with ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:264-274.

- Post CCB, Mens JWM, Haverkort MAD, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ preferences in adjuvant treatment for high-risk endometrial cancer: implications for shared decision making. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:727-733.

- Sanjida S, Janda M, McPhail SM, et al. How many patients enter endometrial cancer surgery with psychotropic medication prescriptions, and how many receive a new prescription perioperatively? Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:339-345.

- Wall JA, Lipking K, Smith HJ, et al. Moderate to severe distress in half of ovarian cancer patients undergoing treatment highlights a need for more proactive symptom and psychosocial management. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;166:503-507.

- Wu TT, Pan HW, Kuo HC, et al. Concomitant benefits of an auricular acupressure intervention for women with cancer on family caregiver sleep quality. Cancer Nurs. 2021;44:E323-E330.

- Bodurtha Smith AJ, Pena D, Ko E. Insurance-mediated disparities in gynecologic oncology care. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:305-312.

- Cheewakriangkrai C, Kietpeerakool C, Charoenkwan K, et al. Health education interventions to promote early presentation and referral for women with symptoms of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:CD013253.

- Chi Y, Thaker K, He D, et al. Knowledge acquisition and social support in online health communities: analysis of an online ovarian cancer community. JMIR Cancer. 2022;8:e39643.

- Cusimano MC, Simpson AN, Han A, et al. Barriers to care for women with low-grade endometrial cancer and morbid obesity: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026872.

- de Rooij BH, Ezendam NPM, Vos MC, et al. Patients’ information coping styles influence the benefit of a survivorship care plan in the ROGY Care Trial: new insights for tailored delivery. Cancer. 2019;125:788-797.

- Dunn C, Campbell S, Marku N, et al. Can social media be used as a community-building and support tool among Jewish women impacted by breast and ovarian cancer? An evidence-based observational report. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;10:51.

- Hill EM, Frost A. Loneliness and psychological distress in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer: examining the role of self-perceived burden, social support seeking, and social network diversity. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29:195-205.

- Jacobs C, Patch C, Michie S. Communication about genetic testing with breast and ovarian cancer patients: a scoping review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:511-524.

- Kargo AS, Coulter A, Jensen PT, Steffensen KD. Proactive use of PROMs in ovarian cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:63.

- Kunos CA, Abdallah R. Financial toxicity encountered in therapeutic radiopharmaceutical clinical development for ovarian cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;13:181.

- Lee H, Reilly M, Bruner DW, et al. Obesity and patient-reported sexual health outcomes in gynecologic cancer survivors: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2022;45:664-679.

- Swiecki-Sikora AL, Craig AD, Chu CS. Financial toxicity in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022:ijgc-2022-003594.

- Temkin SM, Smeltzer MP, Dawkins MD, et al. Improving the quality of care for patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: program components, implementation barriers, and recommendations. Cancer. 2022;128: 654-664.

- Tercyak KP, Bronheim SM, Kahn N, et al. Cancer genetic health communication in families tested for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer risk: a qualitative investigation of impact on children’s genetic health literacy and psychosocial adjustment. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9:493-503.

- Vogel RI, Niendorf K, Petzel S, et al. A patient-centered mobile health application to motivate use of genetic counseling among women with ovarian cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:100-107.