Compared with other patients with cancer, long-term survivors with metastatic disease have not been extensively studied, and not enough is known about the needs of individuals dealing with these difficult diagnoses, according to Cassie Osborne, RN, MSN, OCN, ONN-CG, an oncology nurse navigator at Community Health Network in Indianapolis, IN. Many of these patients, who are often considered “incurable but treatable,” want support and survivorship care but are unable to find it.

But navigators are crucial to making these patients with advanced cancer feel seen and heard and are in a unique position to empower them, educate them, and advocate for them. At the AONN+ Virtual Midyear Conference, Ms Osborne provided an in-depth look at survivorship care for stage IV cancer patients and armed navigators with the tools and resources to support their unique needs.

A Growing Population

Patients with metastatic cancer are now living longer and longer due to improved treatment options, increased availability of therapies, and targeted personal medicine.

According to the American Cancer Society, an estimated 26 million cancer survivors will be living in the United States by the year 2040. “This number includes those who are living with metastatic disease, which is our goal,” she said. “We want people to live longer and longer with their cancer, and this population just keeps growing and growing.”

Defining a “Survivor”

The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship states that survivorship begins at the diagnosis of cancer. So “survivor” includes individuals who are posttreatment and cancer-free, on active surveillance and not in treatment, living with intermittent need for treatment, and with metastatic disease.

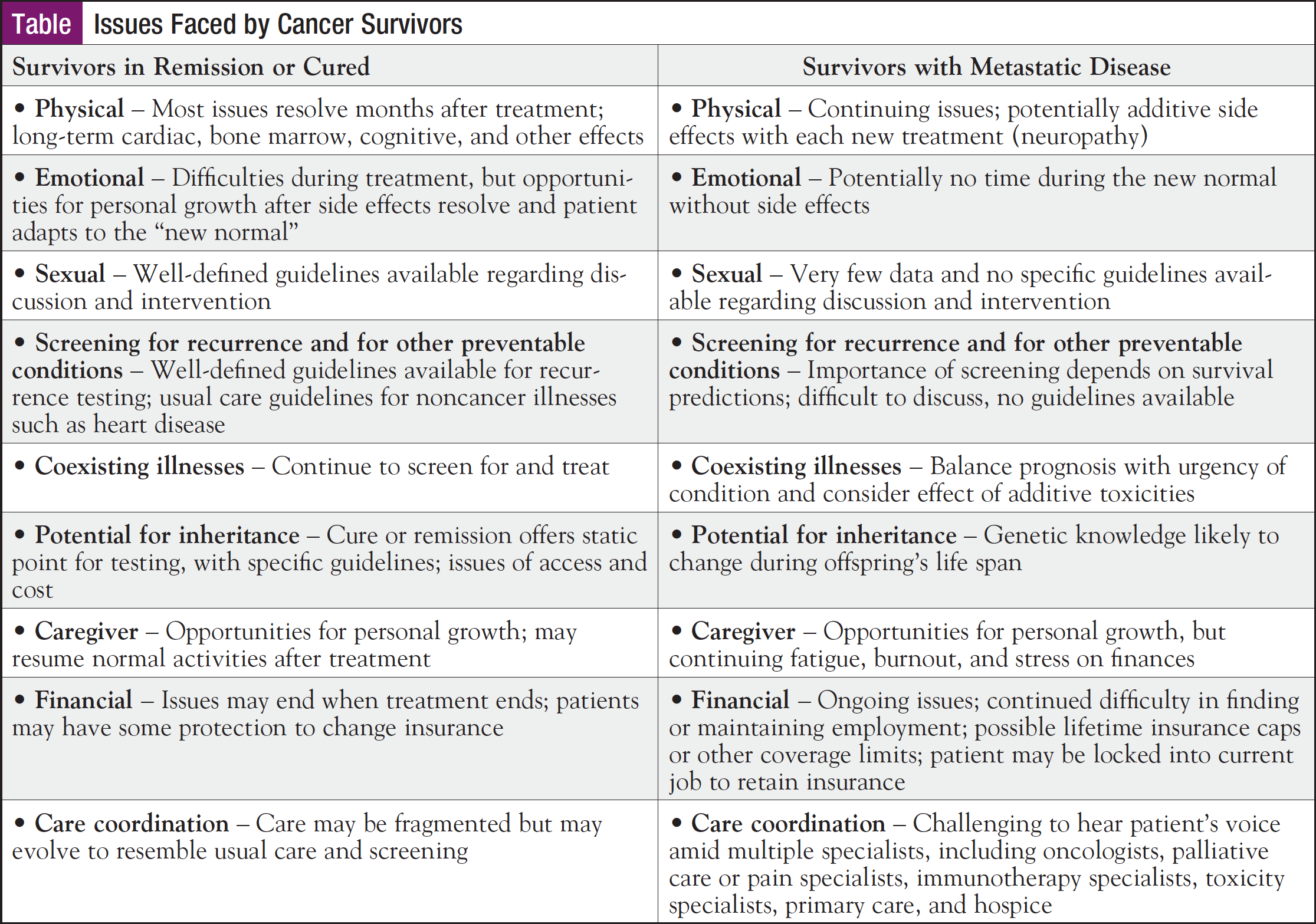

But although the term “survivorship” applies to a broad range of people who have been diagnosed with cancer, Ms Osborne pointed out that the issues and needs of patients in these different stages are unique, as described in the Table.

Advocating for Patients with Metastatic Disease

Although it’s a growing population, long-term survivors with metastatic cancer have still not been sufficiently studied, and current survivorship guidelines from organizations like the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tend to focus on patients who are treated with curative intent.

In a survey conducted by Pfizer in 2009, over half (53%) of women with metastatic breast cancer reported that their condition receives too little public attention, and 38% reported being afraid to talk openly about metastatic breast cancer. Additionally, nearly half (48%) said that their friends and family were uneasy talking about the disease.

According to Ms Osborne, dialogue in the medical community needs to be more inclusive of those living with metastatic disease, and education to reduce the stigma associated with metastatic cancer is sorely needed.

Common Concerns of Metastatic Patients

On a broad scope, common concerns of patients with advanced cancer include prognostic variability, coordination of complex care, symptom management, psychosocial concerns, financial distress, caregiver support, and advance care planning.

Patients with metastatic cancer often worry about prognostic variability, as they do not only fear recurrence but also the progression of their disease and concerns over limited or no treatment options. These patients also tend to worry about emerging statistics and potential eligibility for new treatments in clinical trials and often experience scan anxiety, or “scanxiety.”

“We see this both in the acute setting and in the metastatic setting,” she said. “And I know for a fact that families also feel this; I’m a daughter of a metastatic survivor, and even I have scanxiety right before that scan comes up.”

When it comes to concerns over prognostic variability, navigators can aid patients by helping them sort through the “muck” of cancer care, reiterating education, and moving them through available resources, she said.

Another challenge for metastatic patients is the coordination of complex care involving multiple teams, such as primary care, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology, as well as social workers, dietitians, physical/occupational therapists, chaplaincy (for long-term goals), and palliative care for symptom management.

“I wish there were thousands and thousands of palliative care doctors and teams out there that could help with these patients,” she said. “We need to be making sure that palliative care gets discussed, and the earlier the better. Palliative care does not mean hospice; it means symptom management.”

When it comes to coordinating care among large care teams, according to Ms Osborne, “We need to make sure that the patient’s voice is the one that’s heard the most.”

In terms of symptom management, fatigue is the most common symptom reported with long-term cancer treatment.

“This can cause some issues with adherence to treatment,” she said. “If a patient is having unreported symptoms—or just not feeling well—sometimes they don’t want to take their medications, and they don’t always tell us that they haven’t been taking them.”

But navigators can play an important role in symptom management by educating patients on the use of medications (especially PRN medications like those for pain and nausea), advocating for palliative care involvement, addressing patients’ long-term goals, and encouraging them to join support groups (eg, Cancer Support Community [cancersupportindy.org]).

“Know your local and national support groups, and make sure that you’re able to share this knowledge with your patients,” she said.

When it comes to addressing psychosocial concerns, navigators should be willing to offer support for the tasks that patients have to face on a daily basis, so that they can help to reduce the chaos caused by cancer in their lives. They should also assert that patients’ feelings are normal (while not letting any of their own biases interfere). According to Ms Osborne, working with a collaborative team is an essential part of addressing psychosocial needs, and navigators should always report to the physician and advocate for the patient when further interventions are needed (beyond listening and reassuring words).

Financial distress is a huge concern for many patients with cancer, and especially for those with metastatic disease, because advanced cancer is a highly resource-intensive condition. These patients are often very sick and receive multiple treatment modalities, and generally, they spend more time in various care settings (eg, inpatient care, long-term care, and hospice).

Understandably, high financial burden has been linked to lower quality of life, higher emotional distress, and treatment delays or discontinuation, and in some cases, even increased mortality.

Uninsured or self-pay individuals are often responsible for the full cost of their care, but even insured patients typically have large expenses due to deductibles, copayments, and large out-of-pocket maximum amounts. To combat the financial distress experienced by patients, navigators should make sure their patients have met with financial counseling to work out insurance details (Does the patient have insurance? Are they underinsured?) and to find out whether they meet income requirements for financial assistance. Navigators should also make sure their patients are set up with social workers to help with resources (ie, transportation needs, housing, food), and that they are aware of community resources such as nonprofit organizations that may be available to help.

“Be the squeaky wheel,” she said. “If you have the opportunity to speak up about the costs of cancer care and the burden to patients, please do. We know it’s expensive.”

Patients with advanced cancer often need a great deal of support from caregivers (often friends and family), but navigators should not forget that caregivers need support too.

“As navigators, we need to assess home stressors,” she said. “This will allow us to provide resources such as social work, palliative care, and support groups to the caregiver.”

Advance care planning can be a difficult topic to broach, but discussing goals of care in the beginning may help ease patients’ anxiety and open up the dialogue of advance care planning and patient wishes (keeping in mind cultural considerations during the conversation). Discussing these wishes in the presence of caregivers can also help to ease the burden of decision-making later on.

But according to Ms Osborne, patients with advanced cancer, even when they are in remission, should always discuss goals of care with their navigators in the event that down the line, they can no longer make decisions for themselves.

“Finally, advocate for an increase in us; we need more navigators,” she said. “And take care of yourselves. Self-care in our stressful job is important, not only for you, but for your patients.”