Earlier palliative care for oncology patients with advanced cancer is the new frontier. Palliative care given alongside usual oncologic care in such patients maintains or improves survival and improves quality of life, said Catherine Saiki, CRNP, ACHPN, at the East Coast Regional Meeting of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

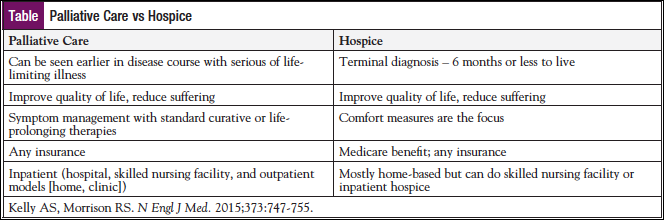

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illness. It is not to be confused with hospice in that it can be provided along with curative treatment, said Ms Saiki, Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner, The Johns Hopkins Hospital Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD.

“The focus of palliative care is on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness—whatever the diagnosis,” she said. The goal is to improve quality of life for the patient and the family. Palliative care is provided by a team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work together with a patient’s other doctors to provide an extra layer of support for patients at any age (Table).

Multiple randomized controlled studies have demonstrated that concurrent palliative care with usual oncology care not only improves quality of life in terms of better symptom control and fewer depressive symptoms but may also extend survival.

Palliative care has evolved over the years. The new recommendation is to integrate palliative care in patients who have an ECOG performance status of 0. “As the disease progresses, or as the treatments that they’re on to control that disease cause a lot of symptoms, palliative care gets a little bit more involved,” said Ms Saiki. “That trajectory moves forward with palliative care playing a more significant role in the patient’s care, and then ultimately hospice care and bereavement.”

The SUPPORT study in 1995 revealed that physicians rarely talked to patients about their preferences for end-of-life care, and fewer than half of physicians knew when patients preferred to avoid cardiopulmonary resuscitation (JAMA. 1995;274:1591-1598).

In a prospective cohort study of end-of-life (EOL) care discussions for patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer, 73% of patients had EOL care discussions, but 55% of those discussions occurred during hospital admission. Oncologists documented EOL care discussions with only 27% of their patients. Among the patients with documented EOL care discussions who died, discussions took place a median of 33 days before death.

Address Prognosis

Failing to address prognosis in discussions with patients can lead to unrealistic expectations. For example, in a large, national, prospective cohort study across 5 states, the majority of patients with metastatic lung (69%) and colorectal (81%) cancers failed to understand that chemotherapy was not at all likely to cure their cancer (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616-1625).

Ms Saiki makes it a point to assess patients’ understanding of their disease. “When people have an improved understanding of their illness, they make very different decisions about what they want and what they don’t want,” she said. “We want to make sure that the language, the ‘medicalese’ that we use doesn’t get misinterpreted, as is often the case.”

Addressing prognosis 2 months before death has been shown to decrease the in-hospital death rate from 51% to 19%. Patients who received early palliative care and who reported an accurate perception of their prognosis were less likely to receive IV chemotherapy near the end of life. Patients who have an accurate perception of their prognosis are also less likely to receive IV chemotherapy close to the end of life. Those who receive chemotherapy in the final 2 weeks are less likely to enroll in hospice or they enroll late.

Early communication of the goals of care reduces use of futile interventions that either prolong the dying process or inflict undue harm at the end of life, said Ms Saiki. They receive care that is more consistent with patient preferences, and bereavement outcomes for the family are improved.

In the setting of metastatic non–small cell lung cancer, patients who were randomized to usual oncology care with palliative care incorporated had improved quality of life, better measures of mood, and improved survival compared with patients assigned to standard care (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-742). Fewer patients in the early palliative care group than in the standard care group received aggressive end-of-life care (33% vs 54%).

The intervention in this study started within 8 weeks of diagnosis, and the palliative care team, which consisted of physicians and nurse practitioners, saw patients once a month on average.

Barriers to communicating prognosis are several. The patient is anxious, maybe in denial, and has a desire to protect family members. The clinician may lack training, comfort, and time. Sometimes, an accurate prognosis is difficult. The system also may present a barrier, as life-sustaining care is the default, systems for end-of-life care are few, systems for recording patient wishes are poor, and often there is ambiguity about who is responsible for the communication.

Be Realistic

Greater than 95% of individuals with cancer want their physician to be realistic when giving the prognosis and believe that they should be told if their illness is terminal, with the majority endorsing that the information be communicated immediately after the diagnosis.

Said Ms Saiki, “That’s not everyone, which is why it’s always important to ask, ‘what’s your understanding of your illness, and how much information do you want to know?’”

Importantly, studies show that patients who recalled discussing plans for end-of-life care received less aggressive care near death and were more likely to have an earlier referral.

No Substitute for Communication

Even in resource-rich comprehensive cancer centers, such as MD Anderson Cancer Center, referrals to palliative care tend to occur late in the course of the disease, if at all. In a review of 1691 patients who died at MD Anderson in 2009/2010, 816 had advanced cancer. Fifty-five percent had no palliative care consult.

Factors that increased the odds of a palliative care consult were being very late in the disease trajectory, being younger, being married, being female, and being under the care of solid tumor service (vs hematology).

Some barriers to palliative care are the following:

- Persistent misconceptions of the role of palliative care

- Interchangeable use of the words “palliative care” and “hospice care,” “end-of-life care,” or “comfort measures only” in practice, in the literature, and in the news

- Oncologists’ fear that they will scare their patients or take hope away

With communication, “there’s no increased depression, anxiety, or hopelessness,” said Ms Saiki. “The only cost to this is increased clinician time.” In fact, those patients with advanced cancer who express acceptance of their prognosis are less likely to feel depressed, anxious, or hopeless.

Changing the conversation words matters, she continued. “Inform and educate your patients, using words like “along with,” “in collaboration with,” “an additional layer of support,” “alongside curative treatments,” and “alongside your usual care,” she advised.

It has been proposed that palliative care has a branding problem. “It’s very interesting because ‘palliative’ is a tough word,” she said. “A lot of people have difficulty saying it. No one knows what it means.”

Another study at MD Anderson tracked outcomes after changing the name of its palliative care program to “supportive care.” It was followed by a 41% increase in the rate of inpatient referrals and no increase in outpatient referrals. Among outpatients, median survival time increased by 1.5 months. Fourteen percent of patients referred had potentially curable disease, compared with 5% prior to the name change, Ms Saiki noted.

The Way Forward

Earlier outpatient palliative care is the new frontier, she said. University of California, San Francisco researchers evaluated more than 900 patients over the course of 2 years. They found that those who were given early referrals (>3 months before they died) versus later referrals had a lower rate of inpatient hospitalizations (33% vs 66%) and a lower rate of intensive care unit utilization (5% vs 20%).

Embedded palliative services serve to improve the clinical team’s understanding of palliative care. Home-based palliative care is a relatively new concept, she said.

Implementation of screening is another important tool gaining traction. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Palliative Care Guideline recommends palliative care screenings for all patients and provides criteria for identifying those in need of a referral to palliative care.

At a minimum, screen for symptoms and set a bar for evaluation by the palliative care team, said Ms Saiki. At one institution in New York, a palliative care consult is initiated for any patient who is taking ≥50 g of fentanyl per hour, she related.

Symptom assessments can be done on paper or can be web-based, depending on finances. Based on the symptom assessment, referrals can be automated and part of the electronic medical record.

At Johns Hopkins, nurses, social workers, and patients can request a palliative care consult. Oncology fellows round with the palliative care team, which is an interdisciplinary team that includes a pharmacist.