To receive credit, complete the posttest at http://ce.lynxcme.com/AONN198-P

Introduction

Navigation in healthcare has seen tremendous growth in recent years and is now considered an integral component of oncology care. At the Sixth Annual Navigation & Survivorship Conference, held October 1-4, 2015, in Atlanta, GA, and its regional West Coast meeting, held May 18-20, 2015, in Seattle, WA, more than 1000 navigation professionals, including oncology nurse navigators, registered nurses, patient navigators, case managers, social workers, and practice managers, convened to discuss the evolving roles of navigation and survivorship in cancer care. This monograph is a synthesis of the proceedings of the 2 meetings; discussion points include best practices in navigation, survivorship, and psychosocial care and implementation of the revised Commission on Cancer (CoC) standards for the benefi t of improved quality of patient care.

Understanding Patient Navigation Programs

Patient navigation refers to the provision of individualized assistance to patients, families, and caregivers to overcome healthcare system barriers (eg, fragmented care) or personal barriers (eg, cultural, fi nancial, educational, spiritual, psychosocial) and facilitate timely access to quality medical and psychosocial care throughout the cancer care trajectory, starting from outreach for screening and early detection, through all phases of treatment, including long-term survivorship or the end of life. The CoC defi nes the standards, data system, quality metrics, and multidisciplinary programs necessary to promote and ensure quality cancer care. The CoC Accreditation Program was designed to ensure that the structures and processes necessary for delivery of high-quality cancer care are in place. For CoC accreditation, the revised 2012 CoC standards (released in January 2014) made a major shift in focus toward 2 areas: (1) patient-centered programs and (2) performance criteria in quality measurement and outcomes.1 Specific standards with respect to these new requirements were added and went into effect in 2015.

According to CoC standard 3.1, “A patient navigation process, driven by a community needs assessment, is established to address healthcare disparities and barriers to care for patients.”1 The patient-centered areas include the provision of treatment and survivorship plans, palliative care services, navigation programs, and psychosocial distress screening.1 Consistent with the CoC’s stance, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes references to patient navigation.2 Such endorsements represent a signifi cant boost to the nascent field of navigation and survivorship care.

The skill and training required to perform navigational tasks are dictated by the phase of the care continuum. Some navigation services may be provided by trained lay navigators; other services may require clinical navigators such as nurses.2 The primary distinction between the two is that the nurse navigator has the clinical background, whereas the lay navigator is not a nurse and is typically focused on the support aspects of care such as scheduling, financial assistance, and psychosocial and community support. Basic requirements of both lay and professional navigators are strong communication, interpersonal, leadership, and organizational skills; the ability to develop collaborative relationships; critical thinking; and a working knowledge of community resources, insurance coverage, and patient support services.

The Oncology Nursing Society defines the primary core competencies for oncology nurse navigators as “the fundamental knowledge, skills, and expertise required to proficiently participate in the care of patients with a past, current, or potential diagnosis of cancer, and assist patients with cancer, families, and caregivers to overcome healthcare system barriers,” which the oncology nurse navigator accomplishes through competent practice in the following areas3:

- Professional role—demonstrate professionalism within both the workplace and community through respectful interactions and effective teamwork

- Education—provide appropriate and timely education to patients, families, and caregivers to facilitate understanding and support informed decision-making

- Coordination of care—facilitate the appropriate and effi cient delivery of healthcare services, both within and across systems, to promote optimal outcomes while delivering patient-centered care

- Communication—demonstrate interpersonal communication skills that enable exchange of ideas and information effectively with patients, families, and colleagues at all levels.

In addition, the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) recognizes operations management, utilization of resources, community outreach/ prevention, and population health as other competency domains essential for nurse navigators.3

Process to Establish Patient Navigation Programs

The patient navigation program is developed, implemented, and evaluated based on the findings of a systematic community needs assessment that identifies disparities and barriers to care relevant to the patient population served by the program. The Public Health Accreditation Board defines the community needs assessment as a document intended to “describe the health of the population, identify areas for health improvement, identify contributing factors that impact health outcomes, and identify community assets and resources that can be mobilized to improve population health.”4

The term “health status disparities” refers to the variation in rates of disease occurrence and disabilities between socioeconomic and geographically defined population groups.5 These disparities in care are complex and often interrelated. According to the Healthy People 2020 initiative of the US Department of Health & Human Services, “Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health, based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.”6 In 2008, approximately 33% of the US population belonged to a racial or ethnic minority population.6 According to the Census Bureau, a large increase in racial and ethnic diversity is projected in upcoming decades, with a minority–majority crossover expected by 2042.7 In addition, in 2008, an estimated 23% of the population lived in rural areas,6 with limited access to cancer care. Since these subpopulations are likely to face significant health disparities, establishing robust patient navigation programs to assist them is of paramount importance to bring about cancer care equality.

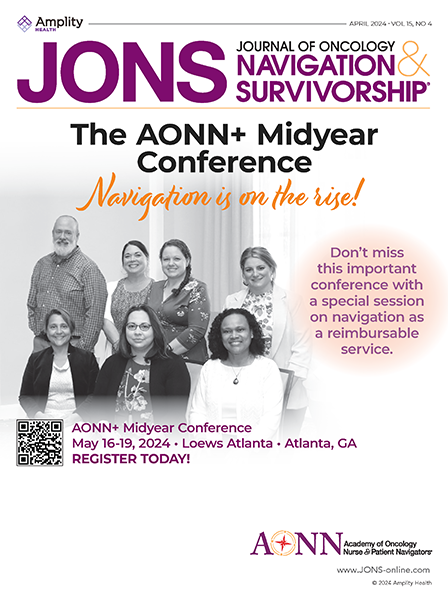

Patients with cancer are confronted with a myriad of psychosocial, economic, and logistic issues. Such barriers to cancer care include knowledge and education gaps, inadequate emotional support, and lack of resources such as transportation, health insurance, employment, legal issues, and prescription assistance. The Pennsylvania Patient Navigator Demonstration Project, which evaluated the utilization of a nonclinical patient navigator program at an urban cancer center, reported that patients on average experienced 1.8 barriers to care, with transportation and insurance issues being the most common.8 Navigators are well-positioned to address many of the identified disparities and barriers to care, and facilitate coordination of care to improve overall health outcomes (Figure 1).9

According to the CoC, the community needs assessment must be conducted every 3 years; the cancer committee must define the scope of this assessment and must be involved in the design and evaluation of results.1 The Hospital Comparison Benchmark Reports and the Cancer Quality Improvement Program Reports are available from the nationally recognized clinical oncology National Cancer Data Base, which is sourced from hospital registry data of more than 1500 CoC-accredited facilities.10 Coupled with the facility’s cancer registry data, these resources may be used to provide primary data on patient age, race/ethnicity, income, education, insurance status, travel distance to facility, and time to first treatment. The cancer committee may also link with the outreach and/or marketing department, or with community-based organizations outside the facility, to obtain additional information.

The community needs assessment, which must be clearly documented in the cancer committee minutes, serves as an essential document to measure compliance with the standards.1 CoC standard 3.1 further clarifies that, “Resources to address identified barriers may be provided either on-site or by referral to community-based or national organizations. The navigation process is evaluated, documented, and reported to the cancer committee annually. The patient navigation process is modified or enhanced each year to address additional barriers identified by the community needs assessment.”1

Quality Metric Standards

Quality measures are vital to sustain and grow cancer survivorship and navigation programs. The new CoC standards specify that a cancer registry and database must be utilized as the basis for monitoring the quality of care and is one of the 4 cornerstones of CoC-accredited programs.1 Quality measures are tools used to “measure or quantify healthcare processes, outcomes, patient perceptions, and organizational structure and/or systems that are associated with the ability to provide high-quality healthcare and/or that relate to one or more quality goals for healthcare.”11 Metrics used in navigation include timeliness of care, barriers to care, referrals to supportive services, referrals to a clinical trials nurse, disease-specific outcome measures, volume, outmigration, survivorship, distress screening, and patient satisfaction.

Navigation and survivorship programs may leverage the cancer registry to provide demographic and treatment-related information for developing the community needs assessment as well as to report patient outcomes. In addition, registry support is key for identifying, leading, and conducting quality improvement studies for program enhancement. Such commitment to centralize and share data resources will allow interdisciplinary data analysis and maintain budget-neutral expense.

Implementing Standards into Practice

According to Danelle Johnston, RN, MSN, OCN, CBCN, Manager of Breast Services at University of Colorado Health, Colorado Springs, and Co-Chair of the AONN+ Evidence into Practice Subcommittee, the process for establishing a patient navigation program is largely driven by the structure of the cancer facility, community needs, and available resources. Foremost, a subcommittee or workgroup that will be responsible for conducting the community needs assessment must be defined. This group, which may include a cancer registrar, a social worker, a navigator, and an administrator, will establish the timeline for the process and goals to accomplish, determine available resources, and defi ne the primary service area. The next step is to collect and document disparities and barriers to care in the primary community area, using available resources such as the cancer registry, as well as by conducting surveys and focus groups with key stakeholders, including patients, families, and healthcare professionals. Following data analysis, the community assessment is generated and a report is given to the cancer committee to formulate the patient navigation process.

To develop implementation strategies for the identified needs, a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis may be conducted. It is recommended that, after identifying the focus of the program, SMART (Specific, Meaningful, Action-Oriented, Realistic, Timely) goals be developed. A few criteria to consider when creating SMART goals include the following: What specifically do you want to achieve? Why is this goal important? What steps will be needed to achieve the goal? How do you know that this goal is achievable? When do you want to achieve the goal? Are the goals consistent with the policies and procedures of the organization? Does the initiative have enough resources? Key elements of an objective are to define the time frame, criterion, target population, and action. For example, “During FY2015, 10% of all curative-intent cancer patients at hospital X will receive a completed survivorship care plan and treatment summary, and be offered a survivorship visit with the nurse practitioner.”

Implementation of the plan with quality metrics and continuous process improvement are the fi nal steps in the process. Continual improvement is vital, and analysis of process and data is imperative to make informed decisions in the evolving healthcare environment and to improve quality of service. In this context, using the PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) model is recommended to implement and analyze quality studies (Figure 2).

Michele Webb, CTR, a cancer registrar in Rancho Cucamonga, CA, made several observations regarding the current compliance to CoC standards, barriers to adoption, and utilization of cancer registries. She mentioned that administrators of cancer facilities have been slow to adopt and support the new CoC standards, which may be attributable to time and cost constraints. Overall, there appears to be a signifi cant lack of a collaborative team approach to build and support the functions of navigation, distress screening, and survivorship. A major area of concern is that repetitive or duplicate data-collection efforts frequently occur across the entire continuum of the cancer program, and often the data are not funneled back into a single repository for future multidisciplinary use. In this context, cancer registries are not utilized to the extent that the CoC standards recommend, highlighting a lack of awareness that the use of registry data to support clinical observations and treatment outcomes may be powerful. Moreover, a cancer registrar is often viewed as a required member of the multidisciplinary team but not as a partner for strategic planning or program development. Ms Webb also stated that facilities vary by how they view and implement their navigation, distress screening, and survivorship programs, with some integrating all 3 aspects into the role of the navigator, whereas others distribute them among multiple staff members.

Value-Based Care

Esther Muscari Desimini, RN, MSN, APRN-BC, Vice President and Administrator at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Tappahannock, VA, discussed the increasing costs of cancer care and their direct impact on the patient, provider, and insurer. She pointed out that fi nancial toxicity has become a guiding principle in cancer treatment. From a patient perspective, the rising out-of-pocket expenses related to cancer care are increasingly impacting patients’ well-being, lifestyle, quality of life, and treatment. In particular, to defray expenses, patients may decide to engage in self-directed reduction in medication doses or avoidance of prescription fulfi llment, which may have dire consequences on treatment outcomes. In one study, the annualized mean net costs of care (adjusted to 2010 dollars) for initial care of a ≥65-year-old patient ranged from $5000 to $115,000, depending on the cancer type; costs related to continued care and during the last year of life were additional. Ms Desimini stressed the importance of a streamlined, team-based approach to cancer care and the incorporation of navigation, survivorship plans, and psychosocial screenings to curb healthcare expenses. Contrary to the view that navigation and survivorship care are costly to introduce, the estimated savings for patients receiving psychosocial interventions was $1759 per person. Ms Desimini also outlined suggested changes in attitudes, behavior, and practice of healthcare professionals (including oncologists) that may reduce fi nancial burden, as well as other cost-saving opportunities in navigation, palliative care, survivorship care, and psychosocial distress screening.

According to Linda D. Bosserman, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at City of Hope Medical Group, Duarte, CA, a cultural change is needed at the levels of the practice, the patient, and the payer to provide value-based, patient-centered cancer care that integrates navigation. It was emphasized that, at the practice level, a comprehensive, evidence-driven, team-based approach is integral for optimal delivery of care, a model in which the navigator is instrumental in coordinating services. Patient engagement in terms of education, shared goals and expectations of therapy, standardized toxicity management, survivorship care, and end-of-life care is imperative for making shared value-based choices. Moving from paper to web portal for collecting patient information was suggested as a means to enable efficient and proactive patient–navigator contact. Finally, payer alignment is necessary to provide affordable and accessible patient care, so that care planning, management, and navigation are appropriately recognized and patient-centered care may be incentivized.

Screening for Psychosocial Distress

Patients may experience psychological, social, financial, and behavioral issues related to their cancer diagnosis or adverse events associated with their disease or treatment. These complications may interfere with treatment plans and adversely affect outcomes. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines on Distress Management, “Distress is a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its symptoms, and its treatments. Distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis.”12 The prevalence of distress in patients with cancer ranges widely in surveys, from 20% to 94%, and appears to depend on the type and stage of the disease, as well as on age, sex, and race.12,13 In a study of 4496 patients with cancer, the overall prevalence of distress was reported to be 35%, with the highest distress experienced by patients with lung cancer.12

Emotional distress is associated with decreased adherence to treatment, diminished quality of life, worse survival, higher medical costs, and overall greater burden on the medical system.12 However, fewer than 50% of patients with cancer are identified and referred for psychosocial help overall, with a particular gap in patients treated in community settings, highlighting the need for psychosocial screening.12 Biopsychosocial screening may be described as a “brief method for prospectively identifying, triaging, and educating patients and their families at risk for cancer-related biopsychosocial complications that undermine the ability to fully benefit from medical care, the efficiency of the clinical encounter, patient satisfaction, and safety.”13 Potential benefits of distress screening are that it provides patients an opportunity to partner with their healthcare team, overcomes patients’ reluctance to ask for help, destigmatizes the issue and allows patients to share their vulnerabilities, and ensures timely referral to supportive services. Successful efforts in Canada have led to distress being adopted as the “sixth vital sign.”12,13 A survey of oncology nurses cited time, staff uncertainties, and ambiguous accountability as barriers to adoption of distress screening, highlighting the need for addressing and standardizing distress management in cancer care.12

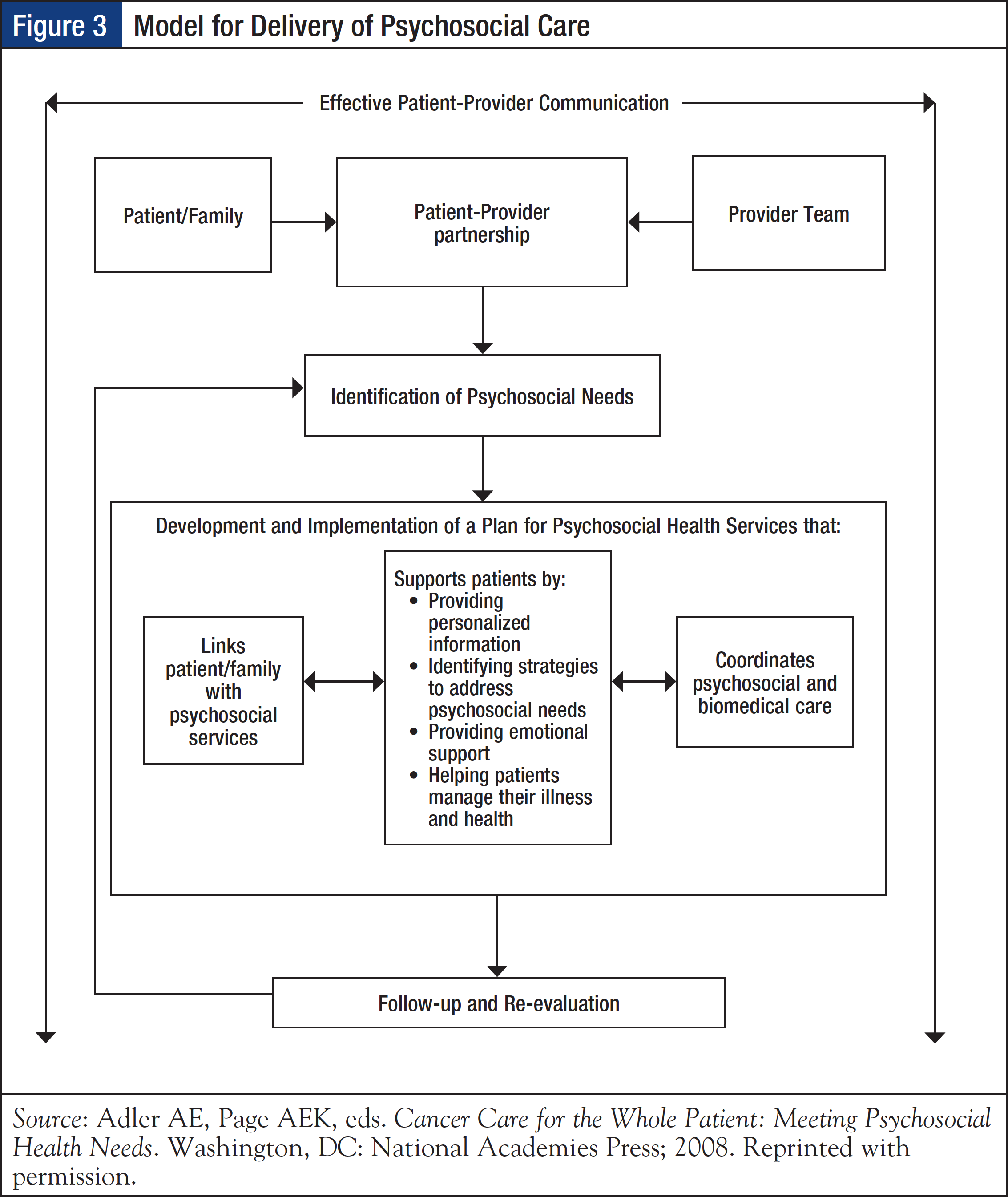

The 2008 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, emphasizes the importance of screening patients for distress and psychosocial health needs as a critical first step to providing high-quality cancer care. In addition, it recommends screening as a part of standard clinical care and as a tool for promoting effective patient–provider communication, as well as to support patients by providing personalized information, identifying strategies to address psychosocial needs, providing emotional support, and helping patients manage their illnesses and health (Figure 3).14

To incorporate distress screening into routine cancer care, CoC standard 3.2 stipulates that “The cancer committee develops and implements a process to integrate and monitor on-site psychosocial distress screening and referral for the provision of psychosocial care.”1 In terms of timing and frequency of screening, the CoC indicates that distress screening must be conducted at least once per patient at a pivotal medical visit to be determined by the program, which may include at the time of diagnosis, presurgical and postsurgical visits, fi rst visit with a medical oncologist to discuss chemotherapy, routine visit with a radiation oncologist, or a postchemotherapy follow- up visit. Understandably, preference for designating the pivotal medical visit is given to times when the patient is at greatest risk for distress (eg, diagnosis, transitions during treatment, transition off treatment). The mode of administration of distress screening is determined by the program.

Screening tools have been shown to be effective in identifying distress and potentially facilitating early intervention. The NCCN-developed distress thermometer and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 are well-known instruments for distress screening and are being widely used. In addition, automated touch-screen technologies, interactive voice response, and web-based assessments have been developed.12

Increasing evidence suggests that distress screening alone is not suffi cient to improve patient outcomes; another critical component is appropriate, timely, and personalized follow-up referrals. A randomized study showed that incorporating both routine distress screening and personalized referral to psychosocial resources led to lower levels of distress at 3 months than did screening without follow-up intervention.12 Future efforts should endeavor to integrate distress screening into the electronic medical record (EMR); tailor for special populations; make screening accessible for web-based screening from home, compatible with newer cell phone and web-based technologies; and provide real-time linkages to community-based physicians and organizations.

Implementing Survivorship Care Plans

In recent years, the purview of patient navigation has expanded beyond the treatment phase to include survivorship, to meet the demands and needs of the growing population of cancer survivors. Advances in cancer diagnosis and treatment have signifi cantly extended survival outcomes in many types of cancer, with an overall 5-year survival of 66% (all sites).15 It is estimated that there are currently approximately 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States, and this number is projected to increase to 19 million by 2024.16 The majority of cancer survivors are aged ≥60 years, a vulnerable population likely to experience comorbidities and other challenges.16

The medical, economic, and healthcare implications of management of survivorship issues are staggering. In a comparison of the health status of cancer survivors and age-matched control subjects, Yabroff and colleagues reported that the burden of illness of cancer survivors was signifi cantly worse than that of the control population, with 31% likely to have fair or poor health outcomes (compared with 18% for controls) and 11% requiring help with activities of daily living (compared with 6% for controls).17 Cancer survivors also had signifi cantly lower utility values and signifi - cantly higher levels of lost productivity. Moreover, these results were consistent across different cancer types and were maintained for many years from the reported diagnosis, thus supporting the need for addressing cancer-related issues throughout the cancer continuum. Unfortunately, current evidence indicates that cancer survivors are not receiving the comprehensive and coordinated follow-up care that they require, and many are lost in transition after they complete treatment.18

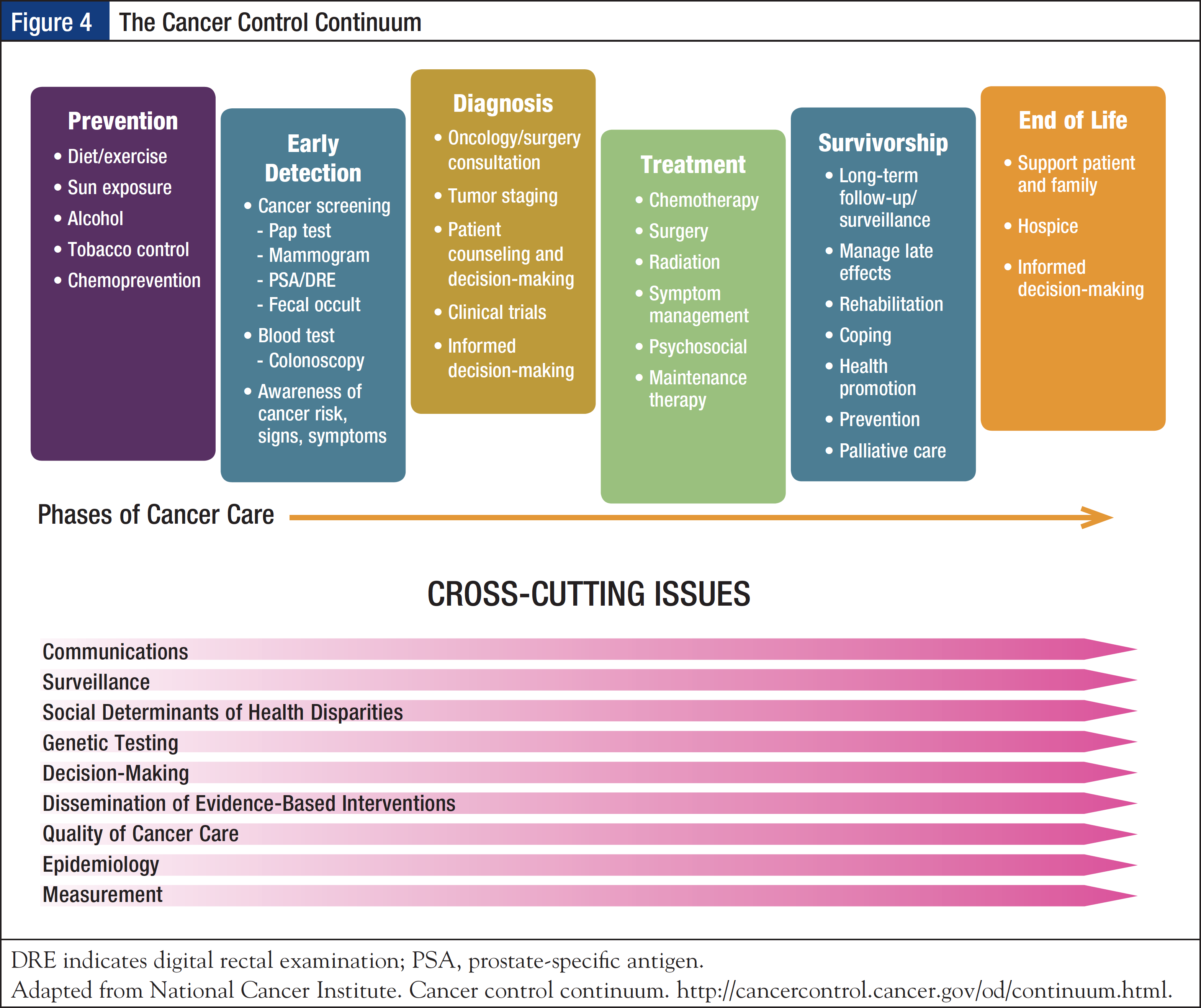

Recognizing the need for a call for action, the IOM 2005 report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition concluded that cancer survivorship is a distinct phase of the cancer trajectory and that a strategy is needed for ongoing clinical care of cancer survivors.18 According to a widely accepted National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship definition, cancer survivorship begins at the time of diagnosis and continues for the balance of life.19 The National Cancer Institute has advanced the concept of the cancer control continuum, which provides a framework of cancer care, including the prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship phases, while acknowledging that these are not discrete entities but require collaboration. In addition, cross-cutting issues may arise and impact each phase; these include surveillance, social determinants of health disparities, genetic testing, and epidemiology outcomes (Figure 4).20

The 2005 IOM report outlined 4 essential components of survivorship care: (1) prevention of recurrent and new cancers, and of other late effects; (2) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, or second cancers, as well as assessment of medical and psychosocial late effects; (3) intervention for consequences of cancer and its treatment; and (4) coordination between specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met.18 The report recommended that patients with cancer who complete treatment be given a survivorship care plan, which should provide a summary of the information critical for the patient’s long-term care, such as their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and potential consequences; include the timing and content of follow-up visits; provide tips on maintaining a healthy lifestyle and preventing recurrent or new cancers; review legal rights affecting employment and insurance; and list local psychological and support services.21,22

A survivorship care plan consists of 2 elements: (1) a comprehensive treatment summary and (2) a follow-up plan. The treatment summary is a complete record of care, including important disease-related characteristics; diagnostic tests performed and results; tumor characteristics such as site, stage, grade, hormonal status, and biomarkers; date of treatment initiation and completion; and treatment administered, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, including agents used, treatment regimen, total dosage, identifying number and title of clinical trials, indicators of treatment response, and toxicities experienced during treatment. Full contact information on treating institutions and key individual providers must be listed, as well as the key point of contact and coordinator of continuing care identified.21,22

The written follow-up care plan must be given to the patient and the primary care provider after completion of acute cancer treatment and must incorporate evidence-based standards of care. It should include the likely course of recovery from treatment-related toxicity, information on potential late and long-term treatment effects, a description of recommended cancer screening and periodic testing (the schedule according to which tests should be performed and by whom), and possible signs of recurrence. In addition, information on the effects of cancer on the marital/partner relationship, sexual functioning, work, and parenting that may indicate a need for psychosocial support must be provided. Specific recommendations for healthy behaviors such as diet, exercise, healthy weight, sunscreen use, virus protection, smoking cessation, and osteoporosis prevention must be included. The follow-up care plan also must contain information on the potential insurance, employment, and financial consequences of cancer and provide referral to counseling, legal aid, and financial assistance as needed.21,22

Consistent with the IOM recommendations, CoC standard 3.3 requires that “The cancer committee develops and implements a process to disseminate a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan to patients with cancer who are completing treatment. The process is monitored, evaluated, and presented at least annually to the cancer committee and documented in minutes.”1 Other requirements of this standard are that the survivorship care plan be prepared by a principal oncology provider with input from the patient’s other care providers, and that it be provided to the patient on completion of treatment.

Aaron D. Bleznak, MD, MBA, FACS, Vice President and Senior Medical Director at Sentara Medical Group and Assistant Professor of Clinical Surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical, Norfolk, VA, who was involved in developing the CoC standards and is currently a CoC surveyor, revealed that in a readiness survey conducted by the CoC member organizations in the summer of 2013, more than 60% of cancer programs indicated that they were unprepared to implement the survivorship care plan. Based on the feedback, the Accreditation Committee decided to phase in this program and changed the established time frame and scope of implementation for CoC standard 3.3. Accordingly, a pilot survivorship care plan process involving 10% of eligible patients had to be implemented by January 1, 2015. It must be implemented in 25% of eligible patients by January 1, 2016, and in 50% of eligible patients by January 1, 2017, with all eligible patients receiving a survivorship care plan by January 1, 2019. During the implementation period, cancer programs should initially concentrate on their most common disease sites, such as breast, colorectal, prostate, early-stage bronchogenic, and lymphoma.

The fi rst step in developing a survivorship care plan is to create a working team that must consist of key stakeholders, including a physician champion, support staff such as a navigator nurse practitioner, an administrator, and the patient. The next step is to create a needs assessment to identify barriers and gaps for cancer survivors during and after treatment, based on which objectives of the survivorship program must be defi ned, national standards for accreditation reviewed, timeline created, and tasks assigned. For effective plan implementation, the model and documentation for the care plan must be chosen, the time to referral into the program must be identifi ed, and the patient intake process must be reviewed and scheduled. Practical insights shared by AONN+ meeting presenters were to model survivorship care plans after the IOM format; to utilize manual and auto completion of plans, such as by autopopulating appropriate data points from the EMR; and to allow a copy-and-paste approach for individualized data for each patient within the EMR. It was emphasized that identified of quality metrics, frequent program evaluation with quality metrics, and use of performance improvement measures are critical for program success.

Specialized Areas of Navigation

Prehabilitation and Rehabilitation

Increasing evidence indicates that cancer survivors experienced a reduced health-related quality of life that is attributable more to physical impairments than psychological issues.23 In a study of 1822 cancer survivors, poor physical health was reported by 24.5% of patients compared with 10% who reported emotional problems, which correlates to approximately 3.3 million and 1.4 million US survivors, respectively.24 Moreover, physical impairments are untreated in 20% to 43% of patients requiring intervention, which may result in considerable physical disability and have associated emotional repercussions.25,26 Therefore, identifying and addressing treatment-induced physical impairments with appropriate rehabilitation measures must be an integral component of patient-centered cancer care. According to CoC eligibility requirement 11, cancer programs must attest to the availability of a “policy or procedure that ensures access to rehabilitation services and identifi es the rehabilitative services that are provided either on-site or by referral.”1

Evidence-based benefits of oncology impairment–driven rehabilitation include improved endurance and cardiovascular conditioning, increased muscular strength, decreased pain, less fatigue, improved balance and coordination, and better neurologic outcomes, which allow patients to achieve a higher level of functioning and higher quality of life. Given that cancer survivors present with varied impairments requiring multimodal interventions, rehabilitation often requires a multi-interdisciplinary team approach. Educating healthcare providers who are involved in the care of patients about impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation care is critical. Using appropriate screening tools to identify physical impairments and integrating functional assessments throughout the continuum of care to determine rehabilitation needs is recommended.23

Prehabilitation refers to “a process on the cancer continuum of care that occurs between the time of cancer diagnosis and the beginning of acute treatment and includes physical and psychological assessments that establish a baseline functional level, identify impairments, and provide interventions that promote physical and psychological health.”23 The goal of prehabilitation is to prevent or limit future impairments, particularly those that may be expected or exacerbated with cancer treatment. Prehabilitation is a multimodal, outcomes-focused approach that typically involves general exercise for conditioning, targeted exercise based on the cancer diagnosis, stress-reduction strategies, nutrition, and smoking cessation.23

Matthew R. LeBlanc, RN, BSN, OCN, an Oncology Rehabilitation Nurse Navigator at Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, MD, emphasized the importance of prehabilitation and rehabilitation for ensuring long-term outcomes for patients who received cancer treatment. He pointed out that despite the availability of prehabilitation and rehabilitation services at most cancer centers, there are gaps in recognizing and providing patient access to these services. To overcome this shortcoming, he outlined steps that may be taken to facilitate patient access to these services, such as screening all patients for rehabilitation needs, meeting rehabilitation professionals in the institution or community, inviting rehabilitation professionals to educate oncology providers, making rehabilitation part of the institution’s nonnegotiable standard of cancer care, and adding rehabilitation professionals to the cancer care team from the time of diagnosis.

Palliative Care

When a patient is in the advanced stage of a disease that is deemed incurable but is not yet in hospice care, there is a shift in treatment goals and navigational needs. During this period, palliative care may improve a patient’s quality of life through management of his or her symptoms, provision of psychosocial support, and coordination of care. Five palliative care skill sets are symptom control, goal setting, communication, interdisciplinary team collaboration, and assistance with healthcare system navigation. Palliative care navigation is distinct from the traditional role, mainly based on the needs of patients with recalcitrant disease and the associated formidable issues of addressing late-stage disease-related symptoms and patient distress caused by disease progression.

Although palliative care is typically delivered late in the disease course when its potential to alter quality and delivery of care is low, increasing evidence supports an early-care model to have a meaningful effect on these outcomes.27 A randomized trial in patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer showed that early palliative care integrated with standard oncologic care led to signifi cantly greater improvements in both quality of life and mood compared with standard care alone.27 Amy Velasquez, RN, BSN, OCN, a Palliative Care Nurse Navigator at the University of Kansas Hospital Cancer Center in Kansas City, recommended introducing palliative care early in the treatment process, ideally while the patient is in treatment. This may allow more time to focus on treatment decisions and advanced care planning, rather than reacting to the acute late-stage symptoms; patients may also be inclined to equate later-stage palliative care with end-of-life care. Importantly, early palliative care may be cost-effective; according to a study of palliative care programs at 8 hospitals, direct cost-savings of $279 per day per palliative care patient discharged alive were realized.28

Conclusions

The current healthcare delivery landscape is complex and daunting for patients with cancer. Patient navigation has gained momentum as a support system that facilitates coordination of care throughout the fragmented healthcare system through the care phases—from diagnosis to treatment and survivorship. Patient navigation is mandated by the CoC standards for cancer program accreditation and is in alignment with many of the ACA principles and priorities. Several patient navigation programs, driven by lay or professional navigators, have been shown to positively impact patient outcomes in terms of addressing barriers to care; implementing interventions to reduce disparities; improving timeliness of care, symptom management, and patient empowerment; providing emotional support; and improving overall patient satisfaction. 29,30 Although there are many challenges to overcome, the patient navigation model brings the delivery of high-quality, patient-centric care closer to reality.

Sabeeha Muneer, PhD, contributed to the development of this article.

References

- Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012 Version 1.2.1: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Updated January 21, 2014. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Freeman HP. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1614-1617.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Oncology nurse navigator core competencies. www.ons.org/sites/default/files/ONNCompetencies_rev.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- Public Health Accreditation Board. Public Health Accreditation Board Standards and Measures. Version 1.5. www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/PHABSM_WEB_LR1.pdf. December 2013. Accessed November 12, 2015.

- Health Services Research Information Central, US National Library of Medicine. Health disparities. www.nlm.nih.gov/hsrinfo/disparities.html. Updated November 10, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2015.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy People 2020: Disparities. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities. Updated November 11, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2015.

- Ortman JM, Guarneri CE; for the United States Census Bureau. United States population projections: 2000 to 2050. www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Fleisher L, Miller SM, Crookes D, et al. Implementation of a theory-based, non-clinical patient navigator program to address barriers in an urban cancer center setting. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2012;3:14-23.

- Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications. Open Access Biomedical Image Search Engine. http://openi.nlm.nih.gov/imgs/512/44/2964637/2964637_1471-2407-10-551-1.png. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- American College of Surgeons. National Cancer Data Base. www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. Accessed November 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality measures. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/index.html. Updated April 17, 2015. Accessed November 5, 2015.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management. Version 2.2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/distress.pdf. July 31, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Loscalzo M, Clark K, Pal S, Piri WF. Role of biopsychosocial screening in cancer care. Cancer J. 2013;19:414-420.

- Adler NE, Page AEK, eds. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4015/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK4015.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. Table 1.5. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/results_merged/topic_survival.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment &am; Survivorship Facts & Figures, 2014-2015. www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042801.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322-1330.

- Hewitt M, Greenfi eld S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. www.nap.edu/catalog/11468/from-cancer-patient-to-cancer-survivor-lost-intransition. Accessed October 31, 2015.

- National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship website. www.canceradvocacy.org/about-us/our-mission. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer control continuum. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/od/continuum.html. Updated January 10, 2011. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Institute of Medicine. Implementing cancer survivorship care planning: workshop summary. www.iom.edu/Reports/2006/Implementing-Cancer-Survivorship-Care-Planning-Workshop-Summary.aspx. December 22, 2006. Accessed October 31, 2015.

- Institute of Medicine. Fact sheet: Cancer survivorship care planning. https://iom.nationalacademies.org/~/media/ Files/Report%20Files/2005/From-Cancer-Patient-to-Cancer-Survivor-Lost-in-Transition/factsheetcareplanning.pdf. November 2005. Accessed October 31, 2015.

- Silver JK, Baima JB, Mayer RS. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:295-317.

- Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, et al. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:2108-2117.

- Cheville AL, Troxel AB, Basford JR, Kornblith AB. Prevalence and treatment patterns of physical impairments in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2621-2629.

- Thorsen L, Gjerset GM, Loge JH, et al. Cancer patients’ needs for rehabilitation services. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:212-222.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-742.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1783-1790.

- Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:237-249.

- Wilcox B, Bruce SD. Patient navigation: a “win-win” for all involved. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:21-25.