Introduction: Cancer survivor numbers are increasing due to enhanced treatment and an aging population; however, survivors often suffer ongoing side effects from cancer and its treatments. Nurses and other key oncology staff are instrumental in working with cancer patients to help screen them for and refer them to critical support services, such as cancer rehabilitation. The purpose of this study was to address whether healthcare providers, particularly oncology nurses, have adequate knowledge about the benefits of cancer rehabilitation to facilitate appropriate patient referrals.

Methods: Members of the Academy of Oncology Nurse Navigators (AONN) were e-mailed and invited to fill out an online survey based on relevant research literature, clinical experience, and expert opinion from multidisciplinary perspectives. Questions included a self-assessment of knowledge about cancer rehabilitation.

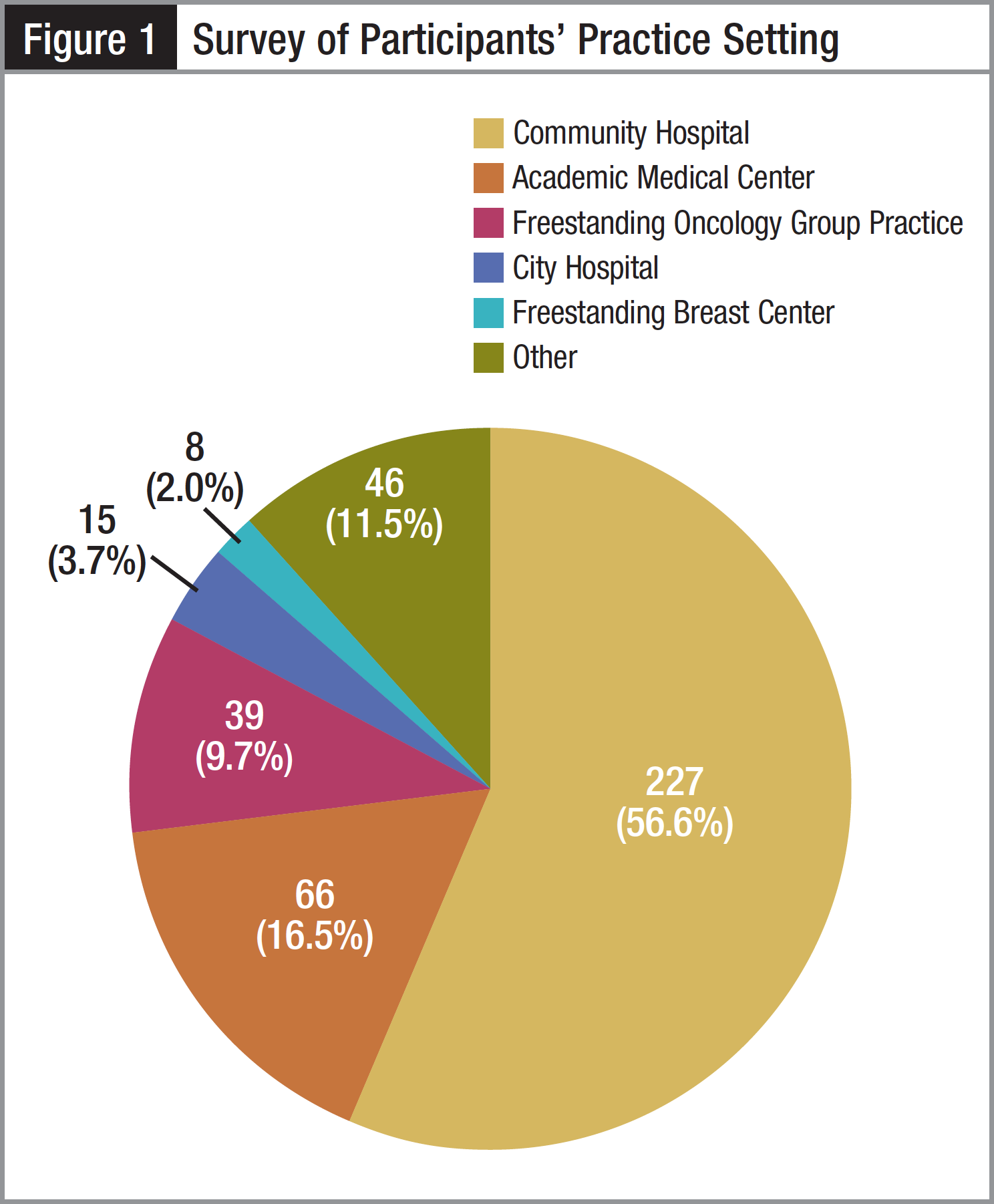

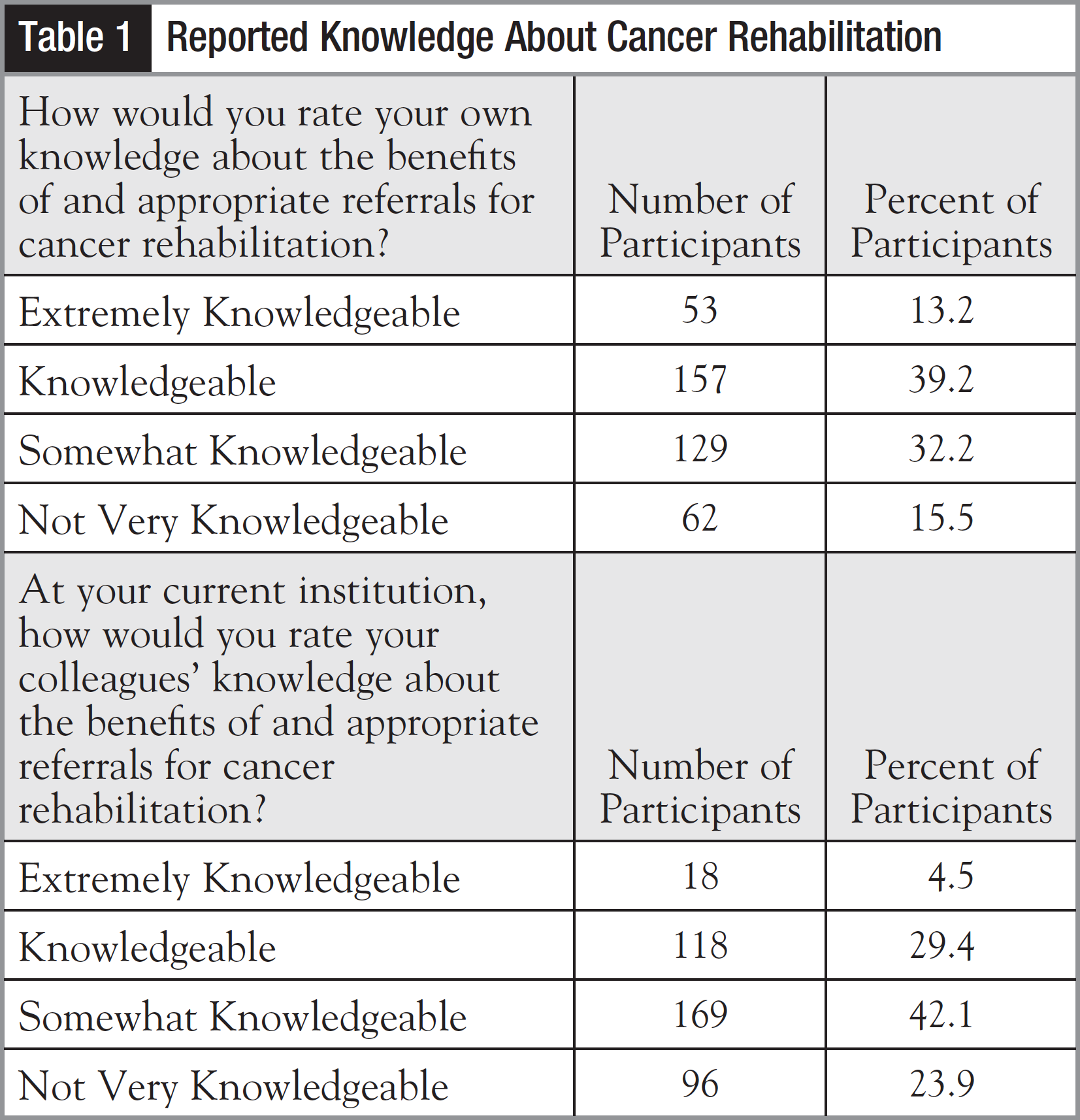

Results: The survey was voluntarily completed by 401 members of the AONN. The majority of respondents were registered nurses (60.3%), and 34.4% identified themselves as oncology nurse navigators. Most of the respondents work in community hospitals (56.6%), academia (16.5%), or freestanding oncology practices (9.7%). When asked “How would you rate your own knowledge about the benefits of and appropriate referrals for cancer rehabilitation?” only 13.2% rated their knowledge in the highest category, “Extremely Knowledgeable.” When asked how they would rate their colleagues’ knowledge, only 4.5% considered their colleagues “Extremely Knowledgeable.” Overall, approximately 50% of the participants rated their own knowledge of the benefits of cancer rehabilitation and referrals in the lowest 2 knowledge categories. The participants generally rated their colleagues’ knowledge even lower, with 66% rating their colleagues in the lowest 2 knowledge categories. Finally, when asked how important the role of nursing navigation is when accessing cancer rehabilitation services, 90% of respondents found it to be “Very Important” or “Important,” while only 10% rated it as “Somewhat Important” or “Not Important.”

Conclusion: Approximately half of the oncology healthcare provider participants rated their own knowledge about the benefits of cancer rehabilitation and appropriate referrals for care as relatively low. Overall, they rated their colleagues’ knowledge even lower than their own. Successful patient-centered cancer care that provides optimal functional and quality-of-life outcomes must incorporate cancer rehabilitation into the care continuum. This study suggests that many oncology healthcare professionals may benefit from further education about the benefits of evidence-based cancer rehabilitation care.

More than 40% of individuals born today will develop some type of cancer during their lifetime.1 It is estimated that 66% of the approximately 12 million individuals living with a diagnosis of cancer today will survive at least 5 years after their diagnosis.1 In 2010, Mariotto and colleagues reported that healthcare costs for approximately 13.8 million cancer survivors were estimated to be $124.57 billion.2 Their research demonstrated that based on current growing incidence and improved survival rates, by 2020 the volume of cancer survivors will swell to at least 18.1 million, generating an annual cost of $157.77 billion that year.2 Indirect costs of cancer survivorship (eg, lost wages, caregiver burdens, transportation, and adaptive equipment) are difficult to quantify in the United States with its decentralized healthcare system. However, in Poland health economists estimate that work loss due to cancer accounts for 0.8% of its gross domestic product (GDP).3 With a US GDP of approximately $15 trillion, the equivalent cost would be $120 billion.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines rehabilitation as “processes intended to enable people with disabilities to reach and maintain optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and/or social function.”4 Historically, nursing, medical, and allied health students have been educated about rehabilitation as it relates primarily to neuromusculoskeletal impairments. The focus of education about these conditions is how to diagnose and treat impairments as well as assist patients with their physical activity level—returning them as closely as possible to their premorbid functional baseline. Regardless of whether a patient has an acute or chronic illness or injury, rehabilitation interventions focus on function and a return to usual daily activities. An interdisciplinary team approach is most advantageous for providing comprehensive care.

Cancer rehabilitation programs were established in the 1970s after research started to demonstrate the efficacy of interventions.5,6 As new studies were published, hospitals and cancer centers developed some rehabilitation services that were usually for either specific patient populations (eg, breast cancer survivors) or particular problems (eg, treating lymphedema). Unfortunately, clinical services may not have kept up with the rapidly growing body of research that supports cancer rehabilitation interventions. In fact, according to a recent meta-analysis of cancer rehabilitation literature (1743 publications retrieved from 1967-2008), cancer rehabilitation publications have grown 11.6 times while the whole field of disease rehabilitation has grown only 7.8 times.7

As mentioned, despite the growing research supporting cancer rehabilitation care, clinical services may not be keeping up. Certainly, there is reason to conclude from the recent literature that many patients have unmet rehabilitation needs. For example, in a 2008 study Cheville and colleagues found that in 163 women with metastatic breast cancer, 92% had at least one physical impairment, and overall 530 impairments were identified.8 More than 90% of the participants needed cancer rehabilitation services, but fewer than 30% received this care. In a 2011 study by Thorsen and colleagues evaluating 1325 survivors of the 10 most prevalent cancers, 63% reported the need for at least 1 rehabilitation service, with physical therapy being the most frequently reported need (43%).9 In that study, 40% of the participants reported unmet rehabilitation needs.

The importance of screening individuals for both physical and psychological impairments and then facilitating appropriate referrals to qualified healthcare providers who are trained to treat them is critical to optimal cancer care.10 Because cancer survivors often have multiple impairments that affect many different organ systems, using a “problem-focused” approach within a single rehabilitation discipline is often not as effective as a more comprehensive approach by a team of professionals. Today, there is a growing trend toward developing cancer survivorship resources, including evidence-based cancer rehabilitation interventions, as a distinct part of cancer care.11 Similar to patients in other models of care, such as those for stroke, spinal cord injury, or orthopedic rehabilitation, cancer survivors are ideally treated by an interdisciplinary team that includes, but is not limited to, physiatrists, rehabilitation nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists. For example, it is somewhat common for a breast cancer patient to experience arm and shoulder range-of-motion issues from surgery, fatigue from radiation, and peripheral neuropathy from chemotherapy. An interdisciplinary approach would allow for these diverse needs to be addressed.12 Similarly, a head and neck cancer survivor may have multiple impairments including speech and swallowing issues as well as cervical range-of-motion limitations. Indeed, cancer survivors are often “complex” patients who have undergone significant physical and emotional trauma and therefore have multiple sequelae. If the goal of optimal function is to be achieved, this complexity requires interventions from more than 1 rehabilitation discipline.

Likely many barriers exist to cancer rehabilitation care.13 One barrier to these unmet needs may be a lack of healthcare providers’ awareness of the benefits of rehabilitation for survivors. Another barrier may be a lack of understanding of the unmet need for these services. Barriers may result from oncology providers believing that treatment-related sequelae are expected and normal and simply need to be tolerated by patients. This translates into a general lack of understanding of the role that rehabilitation may have in reducing or even preventing side effects that are physically challenging and psychologically disabling.14 The aim of this study is to address whether healthcare providers—particularly oncology nurses and a subset of this group, navigators—have adequate knowledge about the benefits of cancer rehabilitation to facilitate appropriate referrals (ie, to navigate patients to this care).

Numerous professional organizations in the United States have recognized the need for formal cancer rehabilitation programs and “best practices” care models. For example, the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) and the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (ARN) have issued a joint position paper recognizing the importance of and need for cancer rehabilitation.15 The American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPMR) and the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) have developed special interest groups for their clinicians who are focusing on cancer rehabilitation in their practices. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) has identified cancer rehabilitation as an emerging area of practice, and the American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA) produced a treatment efficacy summary on swallowing disorders for head and neck cancer.16 The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) has made cancer rehabilitation a key service that accredited facilities must offer either onsite or by referral.17 As the interest in conducting survivorship care research grows, particularly in the face of the anticipated oncology specialist shortage that will likely result in survivors not being seen as often or perhaps at all by their oncologist, there is a need to focus on the role that rehabilitation may play in improving care. Oncology nurses, particularly navigators, are at the forefront of assisting patients in getting the best possible care and addressing their needs during and after treatment. Therefore, it is imperative that they have an in-depth understanding of the benefits of cancer rehabilitation and facilitate appropriate referrals to rehabilitation medicine professionals (particularly physiatrists and physical, occupational, and speech therapists).11

Cancer rehabilitation is one of the key services that must be provided by all CoC-accredited institutions, and nursing navigation is considered an important trend in the provision of high-quality cancer care. In fact, the CoC has announced that patient-centered care is the focus of the new accreditation requirements, and documented navigation is part of these requirements.17 Many hospitals and cancer centers have already seen the value of having nurses drive the navigation process, and others are moving toward fulfilling this new requirement by implementing nursing navigation. Further, implementation of the survivorship care plan, another new CoC requirement, will almost certainly help demonstrate the success of navigation for an individual patient, for hospitals, and even entire systems of care. In addition, the survivor care plan will clearly document whether patients were referred for rehabilitation services. Despite the focus on patient-centered navigation care with implementation of a survivorship care plan that should document rehabilitation services when appropriate, many survivors may not currently, or even in the future, receive appropriate evidence-based rehabilitation interventions.

Methods: The research team developed a unique survey on the basis of the relevant research literature, clinical experience, and expert opinion from multidisciplinary perspectives. Ethics approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins University Internal Review Board. The Academy of Oncology Nurse Navigators (AONN) distributed a dedicated e-mail link to 10,037 potential participants, including members and e-mail subscribers, and posted the survey link in their e-newsletter. All potential respondents were invited to participate in the 25-question online survey beginning in February 2012. The AONN was founded in 2009 and consists of more than 2000 members. Membership is open to all nurse, social work, and lay professional navigators. In addition, the organization welcomes any healthcare professional or advocate.

Results: The survey was voluntarily completed by 401 healthcare professionals, and all participants completed the entire survey without skipping any questions. The majority of the respondents, 242 (60.3%), were registered nurses. Participants could select more than 1 professional category description. One hundred thirty-eight (34.4%) participants identified themselves as oncology nurse navigators, and 29 (7.2%) as nurse practitioners. Non-nurse participants offered numerous descriptions of their professional roles including, but not limited to, researcher or research coordinator (6), social worker (4), registered dietician (3), physician (1), psychologist (1), physical therapist (1), occupational therapist (1), wellness coach (1), quality improvement coordinator (1), and certified tumor registrar (1).

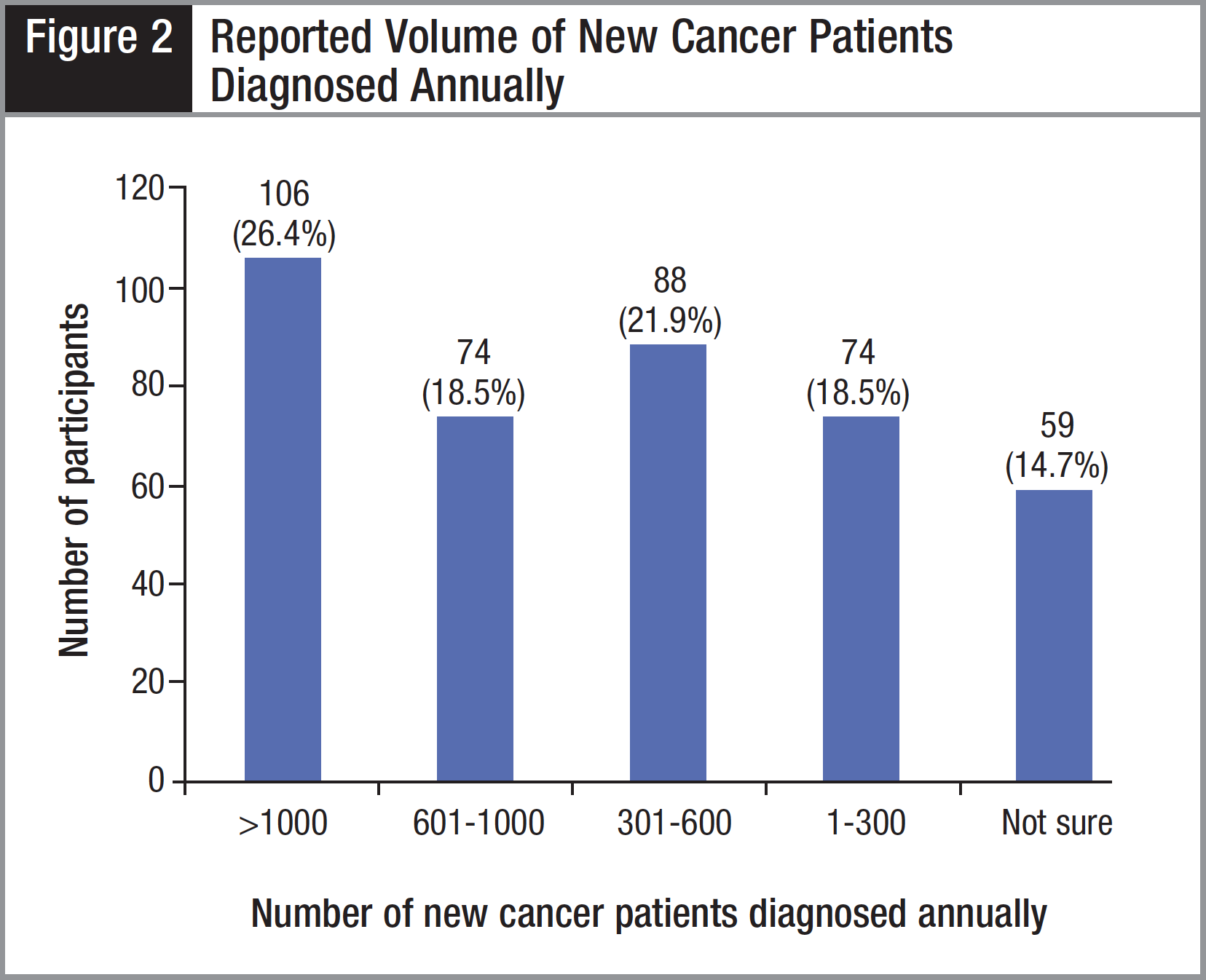

The majority of the participants, 227 (56.6%), reported that they worked at a community hospital (Figure 1). The next most common practice setting, reported by 66 (16.5%) participants, was an academic medical center. In the “Other” category, the most commonly listed settings were National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated comprehensive cancer centers (5; 1.2%) and Veterans Administration/military institutions (4; 1.0%). More than 1 of 4 participants reported working in a high-volume setting with more than 1000 new cancer patients diagnosed annually (Figure 2).

One of the central questions in the survey was, “How would you rate your own knowledge about the benefits of and appropriate referrals for cancer rehabilitation?” Only 53 (13.2%) of the healthcare professionals rated their knowledge in the highest category of “Extremely Knowledgeable” (Table 1). Interestingly, in a follow-up question about how the participants would rate their current colleagues’ knowledge about the benefits of and appropriate referrals for cancer rehabilitation, the ratings were even lower, with only 18 (4.5%) stating that their colleagues were “Extremely Knowledgeable” (Table 1). At the other end of the spectrum, 62 (15.5%) participants rated their own knowledge in the lowest category, “Not Very Knowledgeable,” and an even higher number, 96 (23.9%), rated their colleagues’ knowledge in this lowest category.

A third question, designed to determine how the participants defined the role of nursing navigation in relation to accessing cancer rehabilitation services, was “How important is the nurse navigator’s role in helping patients access cancer rehabilitation services?” More than half of the participants, 225 (56.1%), believed that the nurse navigator role was “Extremely Important,” and 136 (33.9%) selected “Important”—for a total of 361 (90.0%) rating the role of nurse navigators in the top 2 categories of importance (Table 2). Alternately, only 10% of the participants rated the role of nurse navigator in helping patients to access cancer rehabilitation services as a relatively low priority.

In summary, the results of this survey demonstrated that the participants rated their own knowledge of cancer rehabilitation higher than that of their colleagues, and the vast majority of responders believed that nurse navigators have a critical role in helping patients to access these services.

Discussion: It is important for all oncology healthcare professionals to understand the role of evidence-based cancer rehabilitation. Oncology nurse navigators may be uniquely positioned and qualified to facilitate referrals for this care across the cancer care continuum. Therefore, their knowledge of the application and value of cancer rehabilitation services is critical to the success of treatment and optimal patient outcomes. Gaining a better understanding of oncology healthcare professionals’ knowledge and referral practices, with particular attention to nurse navigators, may help in identifying deficits that need to be addressed within the current training curriculum as well as in continuing education once in practice. There is no doubt that cancer rehabilitation is an important component of survivorship care.10 This is the first study designed to evaluate a group of oncology healthcare professionals’ assessment of their knowledge about cancer rehabilitation. AONN members were asked to rate their own knowledge and that of their colleagues about cancer rehabilitation.

When given the choices “Extremely Knowledgeable,” “Knowledgeable,” “Somewhat Knowledgeable,” or “Not Very Knowledgeable,” only 13.2% of participants rated their knowledge about the importance of cancer rehabilitation in the highest category of “Extremely Knowledgeable,” which translated to 86.8% rating themselves as less than extremely knowledgeable. When asked how participants would rate their colleagues’ knowledge, only 4.5% stated that their colleagues were “Extremely Knowledgeable,” which translated to 95.5% of the participants rating their colleagues as less than extremely knowledgeable. Overall, approximately 50% of the participants rated their own knowledge of the benefits of cancer rehabilitation and referrals for care in the lowest 2 knowledge categories. The participants generally rated their colleagues’ knowledge even lower—with approximately 2 of 3 (66%) rating their colleagues in the lowest 2 knowledge categories.

Lack of knowledge about the benefits of and appropriate referrals for cancer rehabilitation may present a major barrier to the provision of this type of medical treatment. It makes sense that all healthcare professionals involved in cancer care should be extremely knowledgeable about appropriate referrals for cancer rehabilitation treatment. The results of this study are concerning and suggest that there is significant room for improvement in meeting this standard and thereby helping to address the unmet rehabilitation needs of survivors.

Nurse navigators play a central role in patient-centered care. Although most healthcare professionals (90% in this study) would agree that oncology nurse navigators should play a critical role in helping patients to access cancer rehabilitation care, nearly 10% of the respondents rated this as “Not Important.” These results confirm the need to further educate healthcare professionals about cancer rehabilitation. Navigation through a complex oncology care continuum, including cancer rehabilitation, is of utmost importance for the best possible outcomes for patients with regard to both quantity and quality of life.

Oncology nurse navigators may have an opportunity to proactively refer patients to cancer rehabilitation programs or service-lines in order to reduce or prevent long-term side effects. Short- and long-term side effects may otherwise go undertreated and perhaps even totally unaddressed. These referrals may also decrease physical, emotional, and financial hardships. The nurse navigator can play an integral part in the assessment and referral process on behalf of newly diagnosed cancer patients, as well as those who have completed treatment and were not afforded the opportunity to receive cancer rehabilitation care.

The first consideration for referral to cancer rehabilitation may be made at the initial contact with the patient. For example, a woman who was just diagnosed with breast cancer and will be undergoing a mastectomy and other treatments may be entering surgery with preexisting shoulder problems (eg, rotator cuff impingement) that postoperatively could lead to more significant shoulder complications including adhesive capsulitis (“frozen shoulder”). Therefore, screening the individual, identifying the impairment, and then facilitating an early referral to cancer rehabilitation, perhaps even before treatment begins or during treatment, may be warranted. This is not to suggest delays in cancer treatment as that may produce adverse outcomes.18

Cancer prehabilitation may also improve functional outcomes—helping newly diagnosed patients to become as physically and emotionally strong as possible prior to the start of oncology interventions.19,20 Unlike the traditional process during which a patient becomes physically deconditioned as a result of treatment, surgery, and/or a sedentary lifestyle, ideal cancer rehabilitation would be introduced early, perhaps even at the prehabilitation stage, so that the patient could maintain function and activity levels during and after treatment.

The philosophy regarding the timing of making a cancer rehabilitation referral and the expectations and outcomes of rehabilitation medicine is changing. Historically the mission of cancer treatment was survival. Patients who were survivors of their disease were advised to accept their “new normal,” which would consist of whatever their physical functioning and emotional well-being became as an outcome of their “successful” cancer treatment. The translation for new normal may be considered to be a medical end point at which further treatment will not improve health outcomes. For many survivors, the advice to accept a new normal or medical end point is offered too soon and without implementation of evidence-based rehabilitation interventions that may improve outcomes. Long after treatment, cancer patients often experience a plethora of side effects, including fatigue, shortness of breath, cardiac complications, pain, depression, range-of-motion limitations, and cognitive functioning problems. Practitioners often view survival as the end point, without enough regard for these quality-of-life issues that remain after cancer treatment ends or, at least, without a thorough understanding of what rehabilitation treatment may provide.

Ideally, the care goals would include preventing as much deconditioning as possible during acute cancer treatments and thereby requiring less reconditioning after treatment is completed. Utilizing this model, the mission is to be proactive in minimizing fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, insomnia, decline in function, lymphedema, pain, and other common side effects associated with some forms of cancer treatment. As the number of individuals diagnosed with cancer has steadily increased along with the number of cancer patients surviving long term, the goals (beyond survival) mandated by patients have evolved.21 Cancer patients today express their opinions and expectations that survival is just 1 component of a good outcome. Quality of life is of utmost importance to cancer survivors.

In summary, this study found that approximately half of the oncology healthcare provider participants rated their own knowledge about the benefits of cancer rehabilitation and appropriate referrals for care as relatively low. Overall, they rated their colleagues’ knowledge as even lower than their own. There is emerging evidence that a large majority of cancer patients could benefit from cancer rehabilitation. Successful patient-centered cancer care that provides optimal functional and quality-of-life outcomes must incorporate cancer rehabilitation into the care continuum. This study suggests that many oncology healthcare professionals may benefit from further education about the benefits of evidence-based cancer rehabilitation care.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge and thank Julie A. Poorman, PhD, for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Disclosures: Lillie D. Shockney, RN, BS, MAS, is the program director for AONN; Julie K. Silver, MD, is co-founder of Oncology Rehab Partners; Laurie Sweet, PT, is an employee of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Corresponding author: Lillie D. Shockney, RN, BS, MAS, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 601 N Caroline St, Room 4161, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

The Role of the Nurse Navigator in Cancer Rehabilitation

The nurse navigator is well positioned to intervene on behalf of the patient in recommending (or, in some settings, actually executing) a referral to cancer rehabilitation. The goals of the rehabilitation interventions are to prevent deconditioning and short- and long-term side effects and to maintain activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) that include not only such tasks as dressing and bathing, but also grocery shopping, returning to work, and other higher level functioning. However, this position requires nurse navigators to be very knowledgeable about the important role that rehabilitation plays in cancer treatment and includes a special need to understand the value of being proactive instead of reactive in making a referral. There is both the need and opportunity for nurse navigators to be skilled at identifying impairments and referring patients appropriately for services to treat these impairments.22

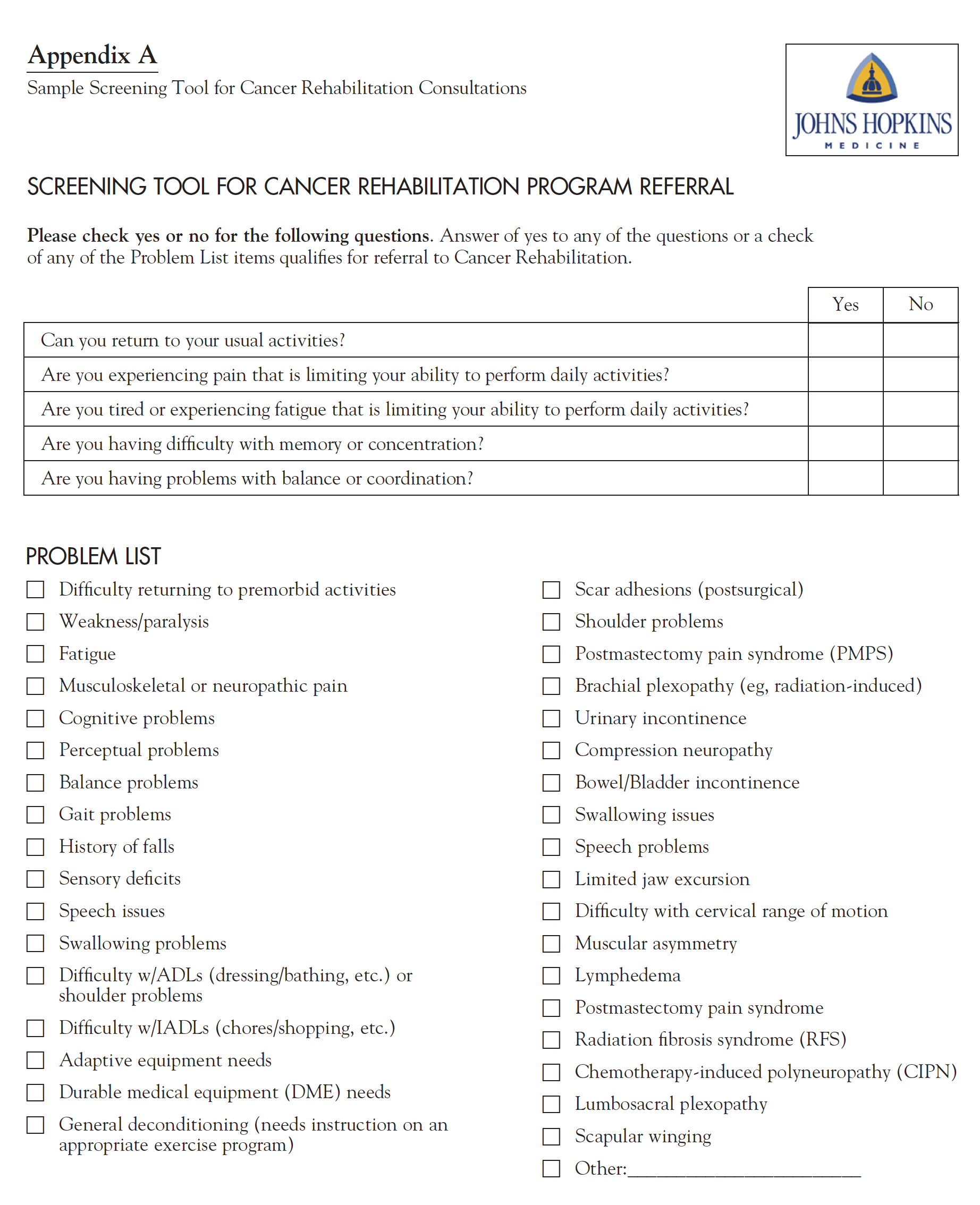

Sample Screening Tool for Cancer Rehabilitation Consultations

It is important to work with the rehabilitation staff to identify patients who would benefit most from their services. Appendix A provides a sample of the quick screening tool that is used at Johns Hopkins to quickly assess whether breast cancer patients should be referred for rehabilitation.

References

1. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: All Sites. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. Published 2011. Accessed March 28, 2012.

2. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. Erratum published in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(8):699.

3. Macioch T, Hermanowski T. The indirect costs of cancer-related absenteeism in the workplace in Poland. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(12):1472-1477.

4. Medical care and rehabilitation: what WHO is doing. World Health Organization Web site. http://www.who.int/disabilities/care/activities/en/. Updated 2012. Accessed August 22, 2012.

5. Dietz JH Jr. Rehabilitation of the cancer patient. Med Clin North Am. 1969;53(3):607-624.

6. Lehmann JF, DeLisa JA, Warren CG, et al. Cancer rehabilitation: assessment of need, development, and evaluation of a model of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978;59(9):410-419.

7. Ugolini D, Neri M, Cesario A, et al. Scientific production in cancer rehabilitation grows higher: a bibliometric analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2012; 20(8):1629-1638.

8. Cheville AL, Troxel AB, Basford JR, Kornblith AB. Prevalence and treatment patterns of physical impairments in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2621-2629.

9. Thorsen L, Gjerset GM, Loge JH, et al. Cancer patients’ needs for rehabilitation services. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):212-222.

10. Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. In press.

11. Silver JK, Gilchrist LS. Cancer rehabilitation with a focus on evidence-based outpatient physical and occupational therapy interventions. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(5 suppl 1):S5-S15.

12. Silver JK. Rehabilitation in women with breast cancer. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):521-537.

13. Silver JK. Strategies to overcome cancer survivorship care barriers. PM&R. 2011;3(6):503-506.

14. Binkley JM, Harris SR, Levangie PK, et al. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(8 Suppl):2207-2216.

15. Oncology Nursing Society and Association of Rehabilitation Nurses: joint position on rehabilitation of people with cancer 2006. Oncology Nursing Society. http://www.ons.org/publications/media/ons/docs/positions/ rehabilitation.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2013.

16. Ashford JR, Logemann JA, McCullough G. Treatment efficacy summary: swallowing disorders (dysphagia) in adults. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Web site. http://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/public/TESDysphagiain Adults.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2012.

17. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. V1.1. American College of Surgeons. Commission on Cancer. http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2012.

18. Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, Kong W, King WD, Booth CM. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2335-2342.

19. Mayo NE, Feldman L, Scott S, et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2011;150(3):505-514.

20. Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. In press.

21. Cheema FN, Abraham NS, Berger DH, et al. Novel approaches to perioperative assessment and intervention may improve long-term outcomes after colorectal cancer resection in older adults. Ann Surg. 2011;253(5):867-874.

22. Schmitz KH, Stout NL, Andrews K, et al. Prospective evaluation of physical rehabilitation needs in breast cancer survivors: a call to action. Cancer. 2012;118(suppl 8):2187-2190.