In the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis, women typically experience significant deterioration in their overall quality of life (QOL), but a program that connects new patients with breast cancer survivors following diagnosis seems to halt the decline. The pilot program, sponsored by Stanford University and WomenCARE, recruited and trained breast cancer survivors to act as peer navigators.

Unlike a patient navigator, whose primary role is to ease the patient’s journey through the medical system, the main role of the program’s peer navigators is to ease the patient’s journey into the new psychosocial realm of living with cancer. After training, the peer navigators provided new patients with emotional support and information for up to 6 months. The study found that patients experienced less-than-expected declines in some QOL measures and improvement in others. QOL for the navigators was neither helped nor hindered.

The investigators believe cancer survivors represent a “largely untapped reservoir of wisdom and experience about coping with illness.” The program offers one way to harness this valuable resource to provide meaningful benefit to new patients.

GOING FROM SURVIVOR TO NAVIGATOR

Success of a peer navigation program hinges on finding the right individuals to serve as peer navigators. For the pilot study, WomenCARE, a community-based nonprofit organization that provides free psychosocial support to women with cancer, referred promising candidates from its support groups. Local clinicians referred other survivors, and some were recruited using newspaper and radio advertisements. Eligible candidates had received a diagnosis of breast cancer an average of 4.5 years earlier, had completed treatment, and were in remission.

The investigative team—Janine Giese-Davis, PhD, Caroline Bliss-Isberg, PhD, Kristin Carson, Path Star, Jessica Donaghy, Matthew J. Cordova, PhD, Nita Stevens, MFT, Lynne Wittenberg, MPH, Connie Batten, MFT, and David Spiegel, MD—rigorously screened the applicants to ensure that everyone selected for the program was a good listener, emotionally stable, and willing to comply with the program’s protocols. First, candidates attended a full-day training course, which focused on listening skills and included an hour of medical instruction from an oncologist. Following this, they attended monthly meetings. At each session, Star, the program’s co-coordinator and matchmaker, and Stevens, a professional therapist, worked to improve navigators’ listening skills through instruction, group discussion, and role playing. A trained clinician supplied medical information and remained on call during the program to answer any questions.

“We put them through a listening exercise to see how they naturally listen when they try to help somebody with a problem,” Star said. Becoming a better listener required the navigators to learn to separate their personal judgments, needs, and medical viewpoints from their interaction with the patient. As a final and firm caveat, the peer navigators were instructed never to second-guess the patient’s oncologists or offer medical advice.

During each monthly session, investigators monitored the peer navigators for signs of emotional distress. Anyone with emotional issues was not matched with a patient. Following the study’s pilot phase, it was decided to require each navigator to attend 2 monthly meetings before being matched. “If they were not going to adhere to coming once a month for supervision, then we didn’t want them out there alone being a peer counselor; it is just too dangerous for everybody. We might have had [a patient] who was suicidal or traumatized, or the peer counselor might get more traumatized as they went along trying to be a good listening ear,” said Giese-Davis, University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine, who was the program’s key scientific investigator. She stressed the importance of reinforcing to the navigators their need for regular supervision.

THE PEER–PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

In all, 42 patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer were matched with 39 peer navigators. Before matching patients with a navigator, investigators asked them to prioritize a list of navigator qualities. Some preferred a navigator who had the same diagnosis or treatment regimen; others asked for a “good listener” or indicated an age or religious preference. Using what was known about the navigators from training sessions, the investigators did their best to optimize the matches.

Either party could initiate contact, which occurred 1 to 4 times each week. Most exchanges were by telephone, but some occurred face-toface or via e-mail. After each meeting, navigators and patients described the interaction using a form designed by the investigators.

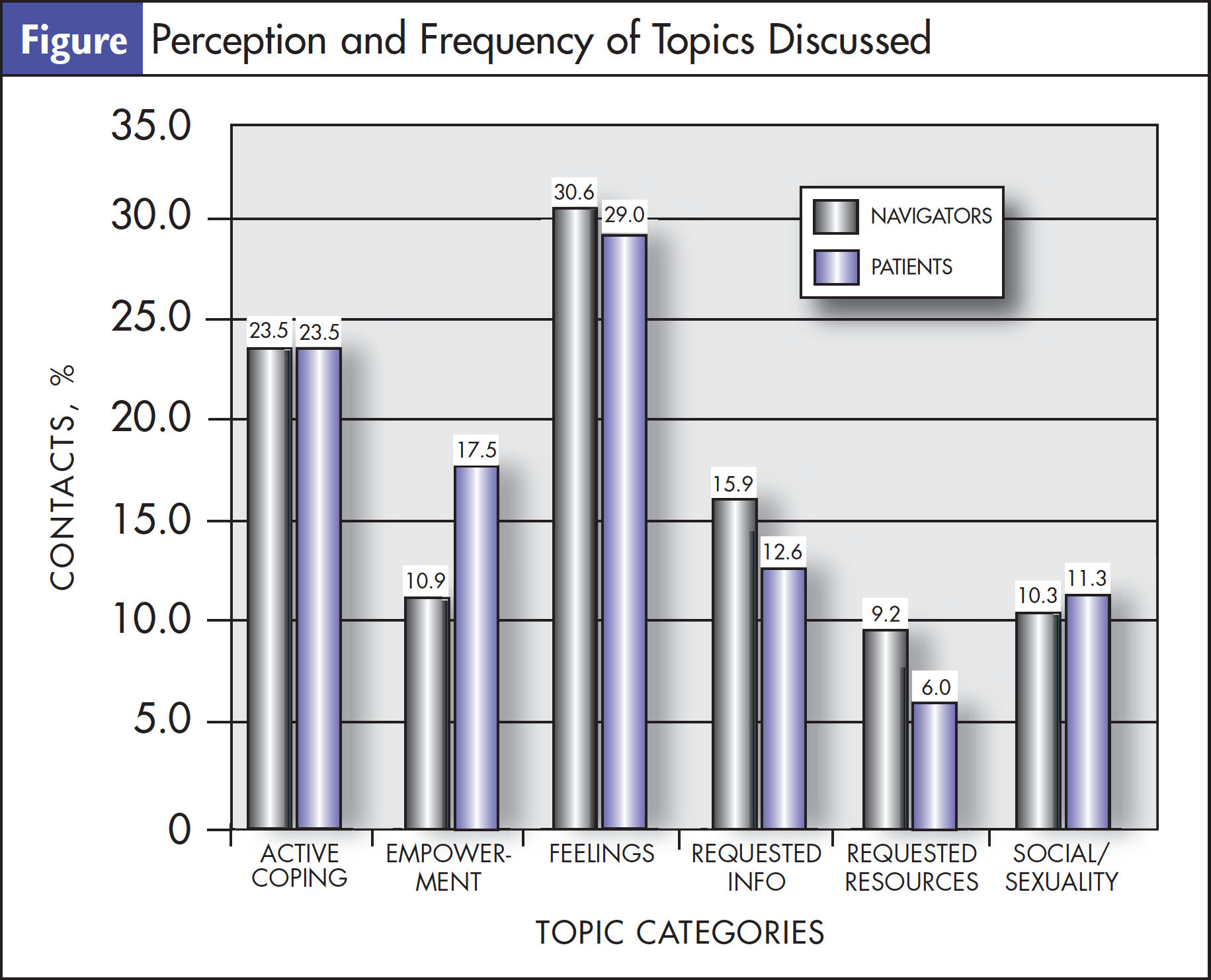

Data showed that navigators were more likely than patients to initiate contact. Most often, the exchanges involved “expression of feelings,” followed by “active coping,” a term the investigators did not define for the participants and thus was not restricted to the physiological effects of cancer, such as treatment response (Figure). The study’s initial design did not establish a breaking point for the peer–patient relationship, but the parties were required to assess and renegotiate their arrangement after 3 months to allow anyone dissatisfied with their partner to request a new one. In the study’s initial phase, the relationships typically dissolved between 4.5 and 6 months.

As the study progressed, the investigators set 6 months as an official end point of the arrangement. “This takes most people through most of their treatment, which was our goal,” said Wittenberg, who is with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine. Giese-Davis added that 6 months was generally enough time for the peer counselors to navigate the person into a support group or to other resources.

The provision to renegotiate at 3 months was kept in place, but the investigative team decided they would also telephone navigators and patients 2 weeks after being matched to ask whether they were satisfied with their partner or wanted to be rematched. “Some women do not want to offend each other and admit that they are unhappy with their match, so we gave them opportunities to tell us,” said Giese-Davis.

At the end of 6 months, patients and navigators were not restricted from continuing a relationship. Giese-Davis said, “Some of those peer counselors continued as sort of friends or informal peer counselors.”

MEASURING RESULTS

Investigators used standardized questionnaires to assess the emotional status of patients and navigators and to evaluate their perceptions about their medical team and breast cancer resources. Assessments were administered at baseline and repeated at 3, 6, and 12 months. After the study, the investigators also conducted separate focus groups with the peer navigators to discuss their views on the program.

For patients, being matched with a peer navigator correlated with a decrease in trauma symptoms— most notably arousal—and improvements in emotional well-being and cancer selfefficacy. Over time, the patients felt less need for breast cancer resources, which the investigators surmised was likely because their informational needs had been met. Although peer navigation did not correlate with significant improvement in the patients’ depression symptoms or social well-being, it might have contributed to less psychosocial deterioration.

As the pilot program progressed, some peer navigators showed signs of trauma, and the investigators decided they needed to take steps to protect their mental health. Bliss-Isberg, Cabrillo College, Aptos, California, a co-principal investigator, offered her perspective as a 4-time cancer survivor: “When you are navigating someone else when you are a survivor yourself, you need support and you need both professional and peer support yourself because it can trigger a lot of stuff you are not aware of.”

During the subsequent randomized clinical trial of this intervention, the group brought in a trauma specialist to help the peer counselors recognize signs of trauma in themselves and the women they were navigating. “We are hoping that was helpful, but we don’t know the answer to that yet,” said Giese-Davis.

Although the program appeared to have no lasting adverse effects on the emotional health of the peer navigators, the investigators were surprised to see no improvement in navigators’ self-efficacy and QOL scores. Although the navigators’ scores remained relatively flat over the course of the program, the investigators believe they did benefit from participating. “One of the wonderful things for the navigators is that it sets a landmark—they are no longer a person livingwith cancer.…They are a survivor, and that mark of becoming a navigator is crucial for that,” explained Star.

The investigators said one unexpected finding was how increasingly dissatisfied the navi - gators became over the course of the study in their interactions with medical professionals. Wittenberg said when asked about this in the focus groups, the navigators indicated that they “noticed these changes as they were further out from treatment and had less frequent contact with their medical team.”

“The ones who were approximately 2 years out were just far enough out that they [were] now going to their family physician instead of the oncology center,” added Giese-Davis.

The investigators offered a few hypotheses for the navigators’ growing dissatisfaction, including the possibility that they missed the level of attention they had received as cancer patients. Another possibility is that the navigators’ growing medical knowledge made them more aware of apparent gaps in knowledge among members of their assigned patient’s treatment team.

Bliss-Isberg suggested that the navigators’ discussions with medical staff “revealed how much art oncologists have to utilize, as well as the science.” She explained that when an oncologist describes a treatment plan, for example, “the well-informed patient has learned enough through reading, the Internet, and contact with others [to see] what the oncologist does not know.” Bliss-Isberg said no matter how marvelous an oncologist is, it is like any profession. “The more you learn, the more you learn that there are holes in the knowledge base of that profession.” Wittenberg said patients spoke to their navigators about negative experiences they had with their medical team, and this might have influenced navigators’ perceptions of their own medical care.

FUTURE OF THE PROGRAM

Peer navigation is a useful complement to the services that patient and nurse navigators provide. As cancer survivors, peer navigators offer patients new to the cancer experience a perspective on the journey to wellness that clinicians often cannot.

“Once you have had cancer, you have something in common with everyone who has had cancer,” said Bliss-Isberg. The support provided by properly trained peer navigators and the model of survivorship they represent “is something that someone who hasn’t had cancer and hasn’t survived can’t offer,” she added.

For those interested in starting a peer navigation program, the investigational team stressed how critical initial training and ongoing support are to a program’s success. “We are not taught how to communicate; we are not taught how to listen,” said Star. “Of all the things we do in our training, the listening exercise for people to see what their style of listening is…is such an important piece.” They also stressed the need to make sure peer navigators understand how important it is that they do not undermine the clinicians by second-guessing their decisions or offering their own medical advice.

The study investigators believe strongly in the value of peer counseling and hope that their findings will help shape future peer navigation programs. Bliss-Isberg said she hopes changes in the US healthcare system and the growing need for health services make this “the perfect time for peer support to take hold” in the country.

For complete findings, see an initial analysis of the study that appeared in the March 2006 issue of Psycho-Oncology. A subanalysis on the effects of the patients’ and navigators’ marital status on distress and well-being was published in The Breast Journal (Sept/Oct 2010).