Introduction

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is on the rise globally. This increase, combined with multiple etiologies and underlying liver diseases, makes the management of HCC challenging for healthcare professionals and patients alike. Patients diagnosed with HCC may find it daunting to navigate through the various aspects of the complex cancer trajectory. Patient navigation is a nationally recognized model of care that is increasingly becoming a key component of the cancer care delivery landscape. The Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) defines patient navigation as the “...process of providing individualized support to patients, families, and caregivers across the continuum of care, beginning with community outreach to raise awareness and performing cancer screening, through the diagnosis and treatment stages, and until short- and long-term survivorship or end of life.”1

As integral members of a multidisciplinary team, oncology nurse navigators eliminate barriers to timely care and coordinate care across multiple treatment modalities and care path transitions. This publication summarizes the current and evolving treatment landscape for HCC and discusses the various responsibilities the oncology nurse navigator typically encounters, including addressing barriers to effective patient care, imparting patient education throughout the care continuum, promoting medication adherence, coordinating care, and providing palliative and survivorship support.

What Is HCC?

HCC is a primary malignancy of the liver and is associated with poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of 18%.2 It is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of global cancer-related deaths.3 HCC arises in the context of several major risk factors such as chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, infection from viral hepatitis B or C (HBV or HCV), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).4 Its incidence varies geographically depending on the presence or absence of risk factors, with the greatest number of cases occurring in developing countries.5 For example, HBV infection is a predominant risk factor for HCC in most parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, whereas alcoholic liver disease and HCV are the most frequently identified risk factors in Western countries.5,6 It is estimated that 60% to 80% of patients with HCC have underlying cirrhosis.7,8 Notably, cirrhosis can arise in the setting of HBV, HCV, alcohol abuse, or NAFLD and its subtype nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; the leading causes of cirrhosis in the Western world are alcohol abuse and HCV infection.6

The clinical presentation of HCC also varies. Patients are often asymptomatic; therefore, the development of symptoms is a clear indicator of underlying severe liver disease. Other patients may experience early symptoms relating to underlying chronic liver disease before the development of HCC, such as jaundice, weight loss, fatigue, or fluid buildup.9 Therefore, because of the well-established association of cirrhosis with HCC, current recommendations include screening for HCC in patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis to detect the malignancy in its earlier stages.8 Most patients with HCC present with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, palpable mass, and weight loss; other symptoms may include jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, anasarca, ascites, variceal bleeding, paraneoplastic symptoms, and abnormal laboratory values.8,9 Noncirrhotic patients typically are diagnosed at advanced stages of disease as they do not undergo surveillance like cirrhotic patients.3

Diagnosis of HCC is based on imaging results (computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), and serologic markers. The most common tumor marker evaluated is alpha fetoprotein (AFP); imaging modality of choice is MRI.10 Liver biopsy is restricted to select patients who do not have expected HCC findings on CT or MRI or who exhibit nodules ≤1 cm that are difficult to assess.8,11

Current Treatment Strategies for HCC

Management of patients with HCC must address the unique challenges of the underlying liver dysfunction and cancer treatment. The prognosis, treatment options, and outcomes of HCC are largely dictated by the severity of the underlying liver disease and degree of decompensation. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team approach is considered the standard of care and is critical for staging of HCC and formulating an individualized treatment plan to achieve optimal patient outcomes. Typically, the team consists of hepatologists, pathologists, interventional radiologists, oncologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, nurses, and general practitioners.12

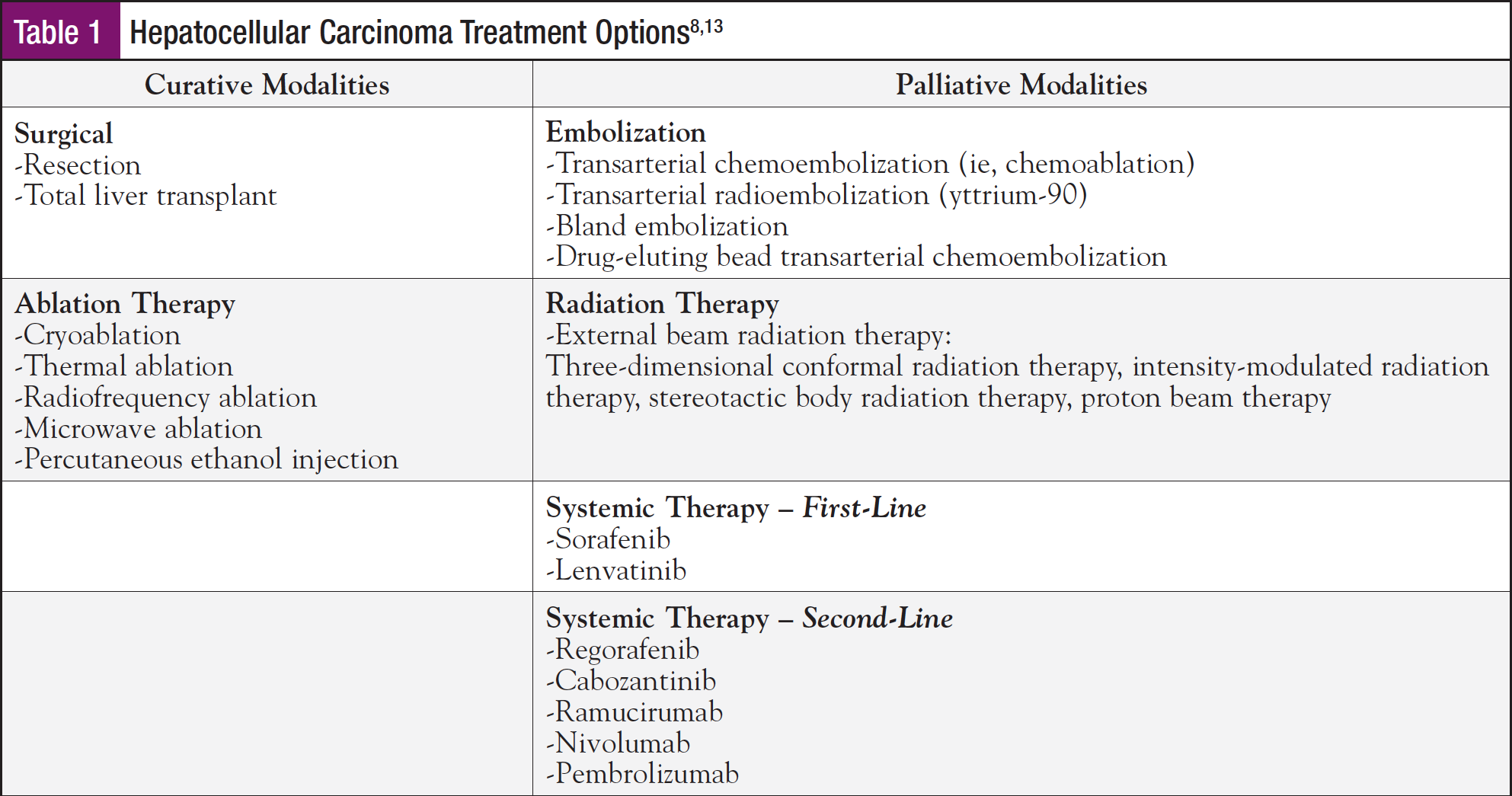

Broadly, treatment options for HCC can be classified as curative and noncurative (palliative care) (Table 1).8,13 Curative therapies include surgical management and locoregional ablation therapies. Noncurative measures providing palliative care are aimed at prolonging survival by slowing tumor progression and include embolization, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy.

Accurate tumor staging is paramount for appropriate patient selection and to determine specific therapeutic interventions.14 There is no absolute staging system used universally for HCC; many staging systems have been developed relative to the geographic regions in which they serve. In the United States, the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification is the most widely used and most effective staging system.14 The 5-stage BCLC staging system correlating each stage with the most appropriate therapies available accounts for the number and size of tumors in the liver as well as a patient’s overall wellness (performance status) and liver function status (defined by the Child-Pugh scoring system).14

Surgery is the treatment of choice in patients with early-stage HCC. Surgical options include partial liver resection or complete liver transplant, with transplantation considered an attractive option since it addresses not only the tumor lesion but also the underlying liver cirrhosis.8 Assessment of functional hepatic reserve is frequently performed using the Child-Pugh classification. Surgical resection of HCC is offered only to patients with well-preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A), whereas liver transplantation is recommended in the context of moderate-to-severe cirrhosis with liver decompensation (ie, patients with Child-Pugh B and C scores).8

Locoregional therapy, including ablation, arterially directed therapies, and radiation therapy, may be treatment options for patients who are not candidates for surgery; these therapies are directed toward inducing selective tumor necrosis and are based on tumor size, location, and underlying liver function. Locoregional therapies may include ablation methods such as radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, thermal ablation, cryoablation, and percutaneous ethanol injection. Side effects of ablation therapy may include abdominal pain or bleeding, but serious side effects are uncommon. Arterially directed techniques include transarterial chemoembolization or radioembolization, which may be administered in combination with ablation therapy or independently.8

Liver transplant is strictly regulated using Milan criteria and successful transplantation requires surveillance afterward, including repeat imaging, monitoring of AFP levels, and other blood work.8 Risk of reinfection also poses an added challenge. In addition, there is a risk for tumor recurrence following liver transplantation.8

Most patients diagnosed with HCC have advanced disease, and only a small percentage are eligible for potentially curative therapies. For patients with extensive liver tumor burden or metastasis, treatment options can include enrollment in a clinical trial, systemic therapy, and supportive care.8 Systemic therapeutic options for unresectable HCC include chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Until recently, the multikinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib was the only systemic first-line agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with unresectable HCC. In 2018, the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor TKI lenvatinib was FDA approved as a first-line agent for patients with unresectable HCC. Subsequent-line therapies that are now available for patients following failure of first-line agents include cabozantinib, regorafenib, ramucirumab, nivolumab, sorafenib (following lenvatinib failure), and pembrolizumab.8 Several other innovative agents and treatment strategies are being investigated and are in various stages of clinical testing. Therefore, clinical trial enrollment is an important treatment option for patients with advanced HCC.

The Specialty of Oncology Nurse Navigation

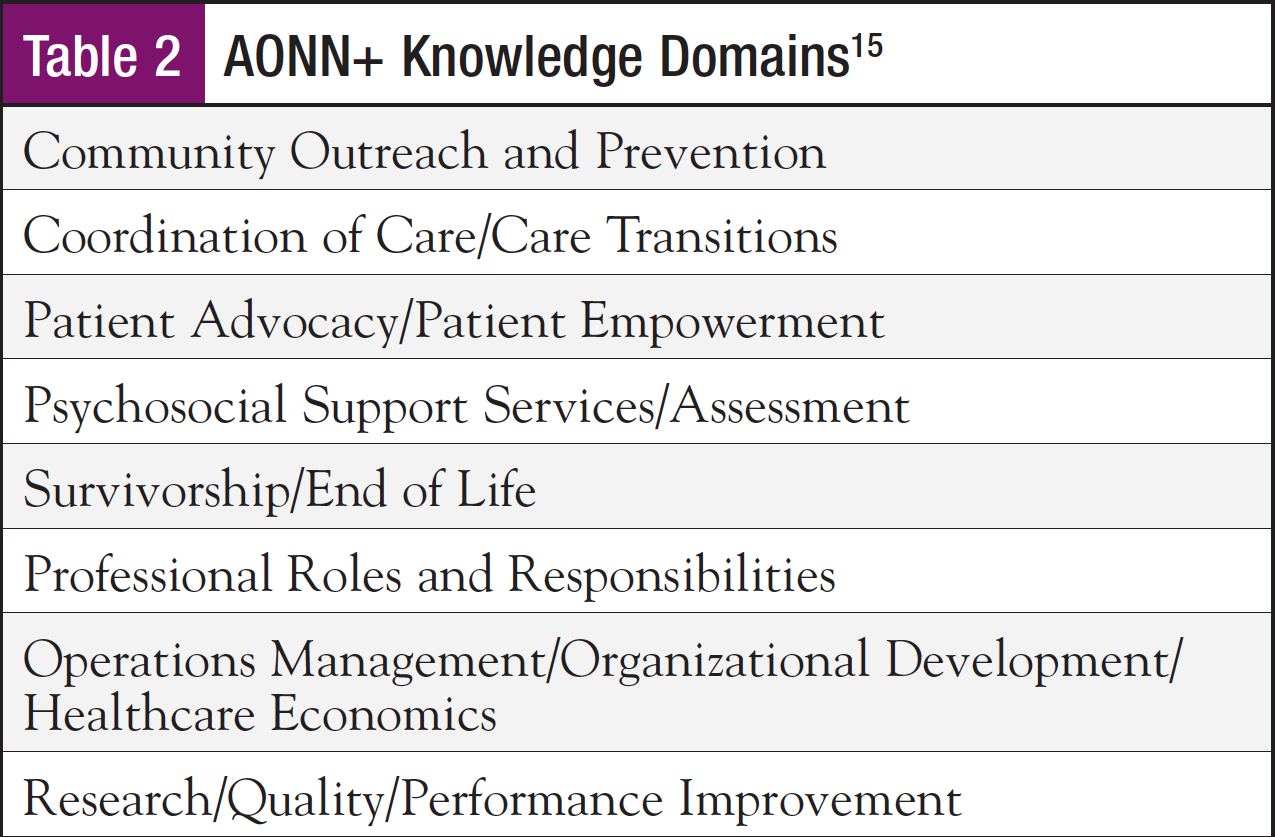

The oncology nurse navigator performs many key functions essential for the delivery of optimal patient care.1 According to AONN+, oncology nurse navigators must demonstrate knowledge in the following overarching domains of care: community outreach and prevention; coordination of care and care transitions; patient advocacy and empowerment; psychosocial support services and assessment; survivorship and end-of-life care; professional roles and responsibilities; operations management, organizational development, and healthcare economics; and research, quality, and performance improvement (Table 2).15 Additional core competencies have been identified by the Oncology Nursing Society, which fall under 3 functional categories: (1) coordination of care, (2) overcoming healthcare system barriers, and (3) education.16

A primary role of the oncology nurse navigator is to serve as a clinically informed liaison between the patient and the healthcare team throughout treatment and survivorship. Nurse navigators work alongside other healthcare professionals, including physicians (eg, surgeons, hepatologists, radiologists, medical oncologists, and transplant surgeons), care providers (eg, physician assistants or nurse practitioners), financial navigators, other nurses, pharmacists, and social workers to deliver optimal care. They streamline the patient’s care and minimize the challenges associated with having several healthcare team members involved in the process. In addition, nurse navigators provide patient education and family support at diagnosis, connect patients with appropriate care and support personnel, and assist with access to community resources.

The Role of Oncology Nurse Navigators in the Management of Patients with HCC

Oncology nurse navigators must tailor their expertise to meet the needs and challenges specific to patients with HCC. They must take into account not only the variables associated with each patient but also the substantial heterogeneity associated with the disease—including the wide range of underlying liver functions and variable tumor lesions (numbers and sizes)—which in turn affect the choice of therapy, treatment-related side effects, and prognosis. Whereas HCC itself is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality, oncology nurse navigators must be vigilant in assessing for underlying liver cirrhosis and its complications, as these factors account for a large proportion of the morbidity and mortality among these patients. Because the identification and treatment of the underlying etiology of liver cirrhosis can partially reverse or slow progression, oncology nurse navigators must engage with patients to understand the key to its development and actively address the issue. For example, alcohol abstinence in patients with alcoholic liver disease has been associated with improvement in fibrosis, normalization of portal pressure, and resolution or reduction of ascites.17

Oncology nurse navigators work as a central point of contact between the patient and an often large and diverse multidisciplinary cancer healthcare team. The fragmented process and sheer scope of care needed to successfully manage a patient with HCC makes the role of the oncology nurse navigator in coordinating care and optimizing delivery of healthcare services indispensable.18 As key members of a multidisciplinary team, nurse navigators participate in case discussions, act as patient advocates on clinical issues, and contribute to treatment decision-making with their knowledge of patients’ preferences for treatment, scheduling, and other considerations.

Building Rapport

To encourage patients with HCC to communicate openly and readily throughout their cancer journey, it is essential that oncology nurse navigators build a good rapport with the patients they serve. This process must begin from the time the oncology nurse navigator first interacts with the patient, typically soon after a diagnosis has been made.

In a patient survey involving 256 patients with HCC, the 5 words used most frequently by patients to describe their feelings upon learning of their diagnosis were “fear,” “worry,” “scared,” “anxiety,” and “shock.”19 In anticipation of the tumultuous emotions these words can elicit, nurse navigators must be prepared to provide comfort and guidance—as well as education and appropriate referrals—to assist patients and their families in coping with the diagnosis of cancer and its potential or expected outcomes.20 An important goal of patient navigation is to ease patient anxiety and improve satisfaction and confidence in the care delivery process; this not only significantly improves quality of life but can also improve clinical outcomes.20 A nurse navigator is best perceived by the patient as a familiar, humanistic, and compassionate presence amid a very daunting and complex process.

Education

Educating patients empowers them to make informed decisions and helps alleviate the fear and distress associated with a diagnosis of HCC. Survey results of patients with HCC indicate that a majority of them felt that they did not receive enough information about HCC and its treatment at the time of their diagnosis.19 In general, patients with cancer have also expressed a desire for more information, comfort, and support upon diagnosis.21,22 In addition, it is well established that insufficient health literacy can limit a patient’s understanding of the treatment plan.23 To truly achieve comprehensive and patient-centered care, treatment strategy and planning needs to be a shared decision-making process that includes a patient’s input. This ensures that patients have a voice in their care and that clinicians are working together with them to make definitive healthcare decisions. In fact, a shared decision-making model has been shown in literature reviews to be preferred by patients diagnosed with cancer.24

The first visit between an oncology nurse navigator and his or her patient is an opportune time to discuss test results, diagnosis, and available treatment options. Patients may not understand how their imaging and laboratory results suggest HCC, nor may they be familiar with the staging of their disease and what that entails for future therapy or prognosis. Nurse navigators can review imaging and laboratory results in tandem with other findings; for example, they can explain to patients that serum AFP alone is not a sensitive or specific diagnostic test for HCC but is useful in conjunction with other test results.8 In the context of underlying liver disease, oncology nurse navigators must help patients understand specific laboratory findings suggestive of cirrhosis, which can include abnormalities in one or more synthetic functions (serum albumin, prothrombin time, and serum bilirubin) and/or a low platelet count.

Assessing for Barriers to Treatment

During their initial encounters with patients, oncology nurse navigators should explore potential barriers to treatment. In general, they must gauge a patient’s health literacy, assess for language or cultural barriers, consider the potential impact of comorbidities, and evaluate the patient’s support system (ie, family and friends) and access to transportation. Current evidence indicates that lack of social support, insurance/financial concerns, and problems with healthcare communications can negatively affect a patient’s follow-up care after a diagnosis has been made.25 Among the HCC patient population, oncology nurse navigators may encounter individuals with a history of intravenous drug abuse, homelessness, alcoholism, and/or lack of family support. These issues can lead to unintended consequences in terms of medication noncompliance, proper management of symptoms (eg, pain management), or ease of access to continued and timely care—all of which need to be addressed. The oncology nurse navigator must provide the patient with appropriate resources to help overcome these barriers once they have been identified.

Treatment

Following the development of a treatment plan, the oncology nurse navigator must explain to patients the therapy that is being recommended based on the stage of HCC and provide information specific to each situation. In the case of surgery, liver-directed therapies, or liver transplantation, oncology nurse navigators must provide patient education on the treatment procedures and explain why they are necessary and inform patients of any testing they will need to undergo before the procedure.

Oncology nurse navigators must also assist in educating patients on preoperative instructions, help set postoperative expectations, and explain anticipated outcomes of the procedure as well as associated risks. Contact between the oncology nurse navigator and the patient must be maintained throughout the entire procedure (including preoperatively) and when imaging for monitoring is prescribed (based on the procedure). For transplant-eligible patients on a liver transplantation waitlist, routine screening must occur to monitor for changes or signs of extrahepatic spread and vascular invasion, and bridge therapies such as locoregional therapies may be considered to decrease tumor progression.8 If patients with HCC are referred to a medical oncologist, oncology nurse navigators help schedule appointments, facilitate the patient’s transition of care to the designated facility, and provide information on therapy-related side effects and their management, as well as the importance of treatment adherence.

Because clinical trial enrollment can be an important avenue for some patients with HCC, oncology nurse navigators must possess a thorough understanding of the process. This helps them keep abreast of trials that are actively enrolling patients with HCC, so that they can direct appropriate patients to participate in these trials and educate them on the prospect of including the trial as a treatment strategy. Patients may have misconceptions about clinical trial participation, which is why oncology nurse navigators must recognize and alleviate their concerns by providing appropriate education and resources.26 Within clinical trials, patients are at risk of known and unknown side effects, as well as the possibility that the treatment may not work; this needs to be conveyed to the patient by the oncology nurse navigator before enrollment.

Management of Disease- and Treatment-Related Adverse Events

It is important that oncology nurse navigators remain cognizant of their patients’ underlying liver disease and be aware of the specific needs presented by this population. The clinical and pathologic courses of HCC are also important aspects of the disease for oncology nurse navigators to comprehend so that they may optimally serve their patients. In addition, oncology nurse navigators need to have a comprehensive awareness of the signs and symptoms of cirrhosis-related complications, as well as worsening of the disease associated with HCC, so that they may educate patients on what to watch for and what to reasonably expect. Symptoms and signs indicating the presence of cirrhosis include abdominal enlargement and/or swelling, insomnia or sleep pattern reversal, vascular spiders, visible collaterals, and palpable liver or spleen. The development of decompensated cirrhosis may be manifested by the presence of jaundice, ascites, portal hypertensive gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and/or encephalopathy. In addition to specific symptom management, oncology nurse navigators must be aware of the repercussions of secondary insults to the liver and engage in prevention efforts such as avoiding hepatotoxic medications and herbal preparations; immunization against hepatitis A and B may be considered for patients with cirrhosis who are seronegative.

To preserve physical functioning and quality of life in patients with HCC, the aggressive management of symptoms related to treatment or the disease process itself is vital.27 For example, some patients with HCC have paraneoplastic syndrome at presentation (such as osteolytic metastasis), which is associated with bone pain and hypercalcemia and requires additional therapy (eg, radiation therapy). Therefore, the oncology nurse navigator must be on the lookout for these instances and be ready to assist patients by providing education about paraneoplastic syndrome and its management. Tumor rupture is an example of a potentially fatal complication of HCC that can occur at any point in the cancer spectrum and results in hypotension, irritation of the peritoneum, and severe abdominal pain. An oncology nurse navigator must be able to recognize and distinguish between routine symptomatology associated with HCC and these more serious symptoms.

Oncology nurse navigators play an essential role in the management of treatment-related adverse events. Toxicities associated with systemic treatments such as sorafenib have been shown to reduce quality of life.19 Side effects related to sorafenib may include rash, hand–foot syndrome, diarrhea, fatigue, increased blood pressure, nausea, and itching.27,28 Early recognition of treatment-related side effects, as well as their timely and appropriate management, are critical for medication adherence, treatment efficacy, and maintenance of quality of life. Therefore, patients must be educated on possible side effects of systemic therapy and how to manage them and be encouraged to convey any symptoms they may be experiencing. The early and ongoing recognition and management of adverse events through this open exchange of information and support between oncology nurse navigators and patients can help minimize the need for dose reduction or interruptions in treatment.28

Pain management is often a challenge for patients with HCC.17 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should generally be avoided because of associated GI toxicities, whereas acetaminophen should be used with caution. Whenever possible, opioids should be avoided in patients with decompensated cirrhosis because of altered hepatic and renal elimination and issues resulting from central nervous system suppression and/or constipation (ie, prolonged half-life).17 In general, the unnecessary use of medication should be avoided in patients with cirrhosis because of potential hepatotoxic or nephrotoxic effects and potential drug–drug interactions.

Medication Adherence

Oncology nurse navigators play an important role in ensuring oral medication compliance in patients with HCC. Medication adherence is defined as the extent to which a patient’s behavior coincides with instructions from a healthcare provider.29 As with other oral medications, the advent of agents such as sorafenib and cabozantinib in the treatment landscape of HCC has shifted the ultimate burden of responsibility for medication adherence to the patient.29,30 In one study of medication compliance, 21% to 28% of patients with HCC were considered nonadherent with oral sorafenib treatment.31 Higher age, number of baseline medications, and number of baseline comorbidities were associated with lower nonadherence, whereas prior procedures were associated with greater nonadherence.31 A systematic literature review has also demonstrated that adherence to certain oral antineoplastic therapies declines significantly over time.32 The consequences of medication nonadherence are serious and can negatively affect overall treatment outcomes, resulting in rates of increased disease progression and mortality. Nonadherence to treatment medication has also been associated with the need for additional physician visits and hospitalizations.29,30

There may be several barriers to medication adherence, including patient- and treatment-related factors. Patient-related factors can include health literacy (lack of understanding of the disease and risks of medication nonadherence), lack of belief or confidence in treatment benefits, age, gender, forgetfulness, comorbid conditions, and financial considerations. Treatment-related factors can include medication side effects, complexity of treatment schedules, and drug–drug interactions.33 In the presence of financial constraints such as lack of health insurance or high out-of-pocket costs, patients may be more inclined to either stop medication altogether or skip doses to make the medication last longer. It is imperative that oncology nurse navigators identify these barriers and address them.

Models of interventions promoting medication adherence are multipronged, and include patient education and communication, management of side effects, behavioral interventions, simplification of medication regimens, and the application of cues to remind patients to take their medicine.29,34 Central to these models is the institution of a collaborative approach to decision-making between the patient and the provider (ie, shared decision-making) that includes specifics regarding the treatment plan, such as medication choice, dosing, and frequency of administration.29 This encourages patients to become empowered and engaged in their own care, allowing them to express their preferences and goals and collaborate with the healthcare provider in making final treatment decisions.

An important component of the shared decision-making model is ongoing education regarding the treatment plan. Relevant issues to broach with patients may include identification of the risks and benefits of treatment and any potential side effects, a review of how treatment-related side effects can be managed, an overview of the risks of drug–drug or drug–food interactions, and a recap of the importance of medication adherence. In addition, oncology nurse navigators may implement routine monitoring and follow-up strategies—such as office visits, web-based patient portals, or phone-based check-ups—with the express intent of identifying concerns related to medication adherence and potentially toxic side effects.30 Several adherence tools and reminder cues may also be employed (eg, pillboxes and diaries, treatment calendars, phone alarms, text messaging, e-mails).35

Survivorship and Psychosocial Considerations

The majority of patients with cancer experience some level of psychosocial distress during the course of their illness.36 If not addressed appropriately, this distress can result in decreased adherence to treatment, poor health-related quality of life, dissatisfaction with medical care, decreased employment functioning, increased health risk behaviors, worse rates of survival, higher medical costs, and an overall greater burden on the medical healthcare system.8,37 The nurse navigator plays an important role in helping patients with HCC maintain their psychosocial well-being throughout treatment and survivorship. When appropriate, a nurse navigator can validate patients’ feelings and educate them on available resources such as psychiatrists or counselors, support groups, or further educational information.8,36

In the context of HCC, an important responsibility of oncology nurse navigators is to assist patients in dealing with the psychosocial intricacies of relapse and survivorship. Patients who cannot receive curative treatments are likely to experience psychosocial distress; this condition often becomes serious enough to require counseling. Patients who undergo resection or transplantation may also experience distress and express concerns about cancer recurrence or complications related to their procedures.13,38 An oncology nurse navigator must be aware of how these different clinical scenarios may play out and thereby affect a patient’s psychosocial well-being, and be ready to offer the emotional support and relevant resources the patient needs.

Following primary treatment of cancer, survivors can experience late effects and/or long-term psychosocial symptoms that can last for years. One systematic review found that among the 4 most common types of cancer (breast, gynecologic, prostate, and rectal/colon), these symptoms included physical limitations, cognitive limitations, depression/anxiety, sleep problems, fatigue, pain, and sexual dysfunctions. These symptoms also varied according to the intensity of treatment (eg, the extent of surgery needed), and patient-related factors such as age and underlying health status at the time of treatment.39 In addition, patients with cancer have significantly higher rates of comorbid conditions and poorer physical and mental health compared with patients without cancer.40

According to a report compiled by the Institute of Medicine in 2005, essential components of the survivorship care period include prevention of new and recurrent cancers and other late effects; surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, or second cancers; assessment of late psychosocial and medical effects; intervention for consequences of cancer and treatment (eg, medical problems, symptoms, psychologic distress, financial and social concerns); and coordination of care between primary care providers and specialists to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met.41 Keeping these key components in mind, an oncology nurse navigator should establish a delivery model that best suits each patient’s unique circumstances and needs.

Patient Resources

In addition to imparting education regarding HCC and its treatment, oncology nurse navigators can also provide information about resources reviewing different aspects of this type of cancer, to help guide patients as they move through the disease spectrum. These may include support groups such as the American Liver Foundation (www.liverfoundation.org) or patient-focused organizations such as Blue Faery: The Adrienne Wilson Liver Cancer Association (www.bluefaery.org). Other resources to share based on an individual patient’s needs may include web-based materials, pamphlets/booklets, and other educational/informational materials.

Conclusion

HCC is associated with a poor prognosis, and the heterogeneity of the disease and the limited treatment options available pose many challenges. Oncology nurse navigators play a key role in multidisciplinary teams that serve patients diagnosed with HCC, in terms of helping patients cope with their diagnosis, providing patient education throughout the cancer care trajectory, assisting in the management of adverse events, promoting medication adherence, serving as a central point of contact for patients and their families, acting as a conduit of information among the treating physicians and between the patient and their healthcare team, and providing coordination of care. As clinically experienced specialists, oncology nurse navigators have the ability and knowledge to individualize patient care and improve overall outcomes by alleviating the burden patients face as they navigate through their initial diagnosis and beyond.

Acknowledgment

Catherine Cantwell, RN, BSN, Complex GI Navigator, JFK Medical Center, Atlantis, FL, contributed to the development of this publication.

References

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+). https://aonnonline.org. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). Cancer Stat Facts: Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- Desai A, Sandhu S, Jin-Ping L, Singh Sandhu D. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: a comprehensive review. World J Hepatol. 2019;11:1-18.

- American Liver Foundation. 2017. Cirrhosis of the liver. https://liverfoundation.org/for-patients/about-the-liver/diseases-of-the-liver/cirrhosis/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- Kew MC. Hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries: prevention, diagnosis and treatment. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:99-104.

- Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838-851.

- Volk ML, Marrero JA. Early detection of liver cancer: diagnosis and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:60-66.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hepatobiliary Carcinoma. Version 3.2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Dimitroulis D, Damaskos C, Valsami S, et al. From diagnosis to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemic problem for both developed and developing world. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5282-5294.

- Charach L, Zusmanovitch L, Charach G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Part 2: clinical presentation and diagnosis. EMJ Hepatol. 2017;5:81-88.

- Balogh J, Victor D III, Asham E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J Hepatolocell Carcinoma. 2016;3:41-53.

- Siddique O, Yoo ER, Perumpail RB, et al. The importance of a multidisciplinary approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:95-100.

- Kumari R, Sahu MK, Tripathy A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: hurdles, advances and prospects. Hepat Oncol. 2018;5:HEP08.

- Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-750.

- Strusowski T, Johnston D. AONN+ evidence-based oncology navigation metrics crosswalk with national oncology standards and indicators. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2018;9:214-221.

- Baileys K, McMullen L, Lubejko B, et al. Nurse navigator core competencies: an update to reflect the evolution of the role. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22:272-281.

- Ismail BES, Cabrera R. Management of liver cirrhosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2013;2:34.

- O’Donoghue P, O’Beirne K, Malago M, et al. Clinical nurse specialist role in setting up a joint hepatocellular carcinoma clinic at a specialist liver unit. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2018;16:S20-S28.

- Gill J, Baiceanu A, Clark PJ, et al. Insights into the hepatocellular carcinoma patient journey: results of the first global quality of life survey. Future Oncol. 2018;14:1701-1710.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Oncology nurse navigator core competencies. www.ons.org/sites/default/files/2017-05/2017_Oncology_Nurse_Navigator_Competencies.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S. No news is not good news: information preferences of patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 1995;4:197-202.

- Hawkins NA, Pollack LA, Leadbetter S, et al. Informational needs of patients and perceived adequacy of information available before and after treatment of cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26:1-16.

- Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, et al. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:134-149.

- Tariman JD, Katz P, Bishop-Royse J, et al. Role competency scale on shared decision-making nurses: development and psychometric properties. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:1-10.

- Hendren S, Chin N, Fisher S, et al. Patients’ barriers to receipt of cancer care, and factors associated with needing more assistance from a patient navigator. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:701-710.

- Napolitano E. Clearing Up Myths and Misconceptions About Clinical Trials. www.mskcc.org/blog/clearing-clinical-trials-myths-and-misconceptions. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Sun VC, Sarna L. Symptom management in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:759-766.

- Pang X, Li G, Lv Y, et al. Effect of specialized nursing intervention on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Biomedical Research. 2017;28:791-796.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487-497.

- Anderson MK, Reff MJ, McMahon RS, et al. The role of the oral oncology nurse navigator. Oncology Issues. 2017;32:26-30.

- Mallick R, Cai J, Wogen J. Predictors of non-adherence to systemic oral therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1701-1708.

- Greer JA, Amoyal N, Nisotel L, et al. A systematic review of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies. Oncologist. 2016;21:354-376.

- Cheung WY. Difficult to swallow: issues affecting optimal adherence to oral anticancer agents. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:265-270.

- Accordino MK, Hershman DL. Disparities and challenges in adherence to oral antineoplastic agents. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:271-276.

- Schneider SM, Hess K, Gosselin T. Interventions to promote adherence with oral agents. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:133-141.

- Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington DC: National Academies Press (US); 2008. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4015/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK4015.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104:2565-2576.

- Lacaze L, Scotte M. Surgical treatment of intra hepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1755-1760.

- Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, et al. It’s not over when it’s over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;40:163-181.

- Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29:41-56.

- Hewitt M; Greenfield S; Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.